The World Has Lost 33% of Its Farmable Land

Contents

During the Paris climate talks last week, researchers from the University of Sheffield’s Grantham Center revealed that in the last 40 years, the world has lost nearly 33% of its farmable land.

The loss is attributed to erosion and pollution, but the effects are expected to be exacerbated by climate change. Meanwhile, global food production is expected to grow by 60% in the next 35 years.

Researchers at the Grantham Center argue that the current intensive agriculture system is unsustainable. Modern agriculture requires heavy use of fertilizers, which “consume 5% of the world’s natural gas production and 2% of the world’s annual energy supply.” This use of fertilizers also allows “nutrients to wash out and pollute fresh coastal waters, causing algal blooms and lethal oxygen depletion,” along with a host of other problems. As fertilizers weaken the soil, heavily ploughed fields can face erosion rates that are “10-100 times greater than [the] rates of soil formation.”

Organic farming typically includes better soil management practices, but crop yields will not be sufficient to feed the growing global population.

In response to these concerns, Grantham Center researchers have called for a sustainable model for intensive agriculture that will incorporate lessons both from history and modern biotechnology. The scientists suggest the following three principles for improved farming practices:

- “Managing soil by direct manure application, rotating annual and cover crops, and practicing no-till agriculture.”

- “Using biotechnology to wean crops off the artificial world we have created for them, enabling plants to initiate and sustain symbioses with soil microbes.”

- “Recycling nutrients from sewage in a modern example of circular economy. Inorganic fertilizers could be manufactured from human sewage in biorefineries operating at industrial or local scales.”

The Grantham researchers recognize that the task of improving our farming situation can’t just fall on farmers’ shoulders. They expect policymakers will also need to get involved.

Speaking to the Guardian, Duncan Cameron, one of the scientists involved in this study, said, “We can’t blame the farmers in this. We need to provide the capitalisation to help them rather than say, ‘Here’s a new policy, go and do it.’ We have the technology. We just need the political will to give us a fighting chance of solving this problem.”

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global non-profit with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Climate & Environment, Recent News

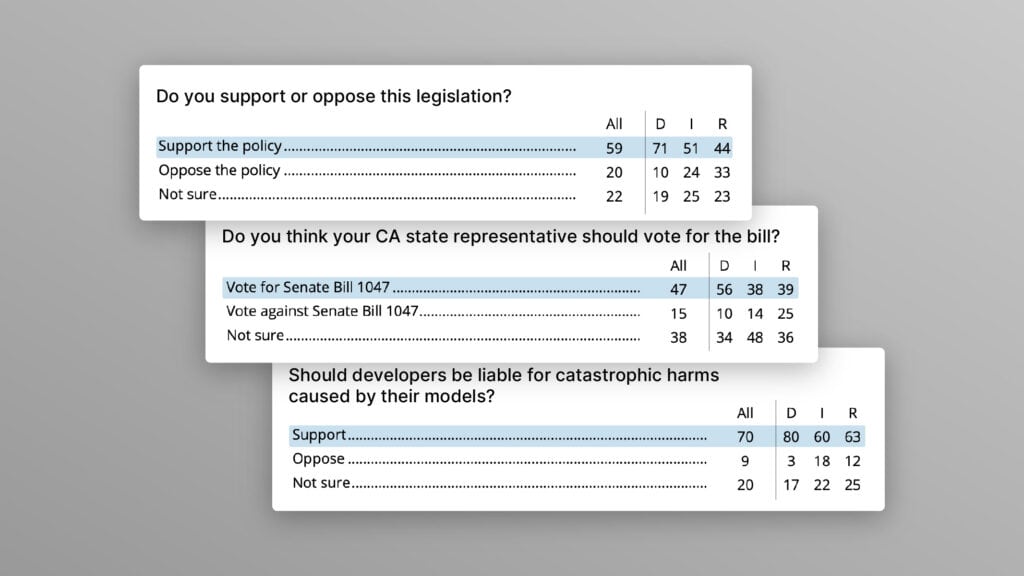

Poll Shows Broad Popularity of CA SB1047 to Regulate AI

FLI Praises AI Whistleblowers While Calling for Stronger Protections and Regulation