On AI, Jewish Thought Has Something Distinct to Say

Contents

David Zvi Kalman is the host of the Belief in the Future podcast, a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, and Senior Advisor at Sinai and Synapses. Kalman is the owner of Print-O-Craft Press, an independent publishing house, and his own work has seen wide academic and popular publication. He holds a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania and a BA from the University of Toronto. He blogs regularly on Jello Menorah.

The world’s religious thinkers are currently trying to figure out what to do about AI—albeit in fits and starts. Conferences are being convened. Books and articles are being commissioned. Google “Muslim approaches to AI” or “Catholic approaches to AI” and real substance will pop up. Most of this has happened in the last five years. The wheels are really turning.

But—and I say this as someone who’s been watching closely—it’s all pretty slow, and in relation to an industry which values speed above all that’s a huge problem. Religion cannot afford to be slow in a world that is moving faster than ever before.

The way you can tell it’s slow is that it is not yet possible to answer the following question: Are Muslim/Catholic/Jewish/etc. approaches to AI essentially identical, or do they differ in significant ways—and if they differ, where exactly do they differ?

This is an important question to press upon because it forces religious thinkers to get serious and decide if they want to be ethical leaders or ethical followers. It’s easy to say that your faith dictates that AI, say, not be used to exploit the weak and vulnerable; in fact it would be odd if it didn’t, because literally everybody agrees with this, pious and otherwise. A religious denomination that promotes such consensus positions isn’t going to make enemies, but it also risks getting lost in a sea of nodding heads. Indeed, if everyone wants the same thing it is often perceived as a liability to use religious language to say so, since such language can be alienating in a secular society.

Perspectives of Traditional Religions on Positive AI Futures

An introduction to our work to support the perspectives of traditional religions on human futures with AI.

This is why I am drawn to the points of disagreement, where a religious group is saying something about AI that others might not. As a Jewish thinker who works on tech issues and who has spent time speaking with AI ethicists from other faiths, here are the places where I believe Judaism’s emergent AI ethics is doing something distinctive.

“The image of God” is not just about biology

AI has demonstrated humanlike capabilities for any number of tasks. Inasmuch as humans understand their worth in relation to their unique capabilities, this has raised concerns about the erosion of human value. Both Christians and Jews have responded to this alarm by emphasizing the religious idea that human beings have a special status as the only creatures to have been created “in the image of God” (Genesis 1:27).

However, not everyone uses this phrase the same way. The Southern Baptist Convention, for example, understands it to be an elevation of biological humans—including embryos—above all other entities. This understanding motivates the denomination’s opposition to IVF and abortion, as well as the categorical denial of personhood to all AIs, no matter how humanlike they become. Humans are simply ontologically separate from both animals and machines.

In my understanding, Jewish thought takes a different path. Yes, biological human beings have infinite value, but that value is also tied to what we perceive as being human, with degrees of personhood available for liminal cases. This approach lies behind Judaism’s complex position on abortion, among other things. It also—in my opinion—means that we should seriously consider assigning some level of personhood to machines that present themselves as people. While some will have the knee-jerk response that this will impinge on human rights, I believe the opposite is true. We are much more likely to discount people if we see their abilities as being “only” equivalent to what an AI can achieve. An AI’s ability to act human should raise up the AI, not diminish the human. By the same token, the intentional creation of humanlike software is unlike the creation of other sorts of software. Just as AI firms have explicitly compared their products to nuclear technology in terms of its promise and danger, we must acknowledge that it also shares something with the creation of human life—and developers should understand this as a mandate to develop and maintain their models extremely carefully.

The obvious drawback of this approach is that it could be used to dehumanize people with disabilities. Because of this, I should emphasize that I understand the Jewish approach to be a hybrid, with biological humanity and human behavior patterns both contributing to how we place value on creatures and machines. This perspective has not been fleshed out, so to speak, but the divergence is already becoming clear.

The role of AI in religious text study

Within Judaism, text study isn’t just a means to understand the tradition; it’s a ritual act in its own right, one that all Jews (though in practice far more men than women) are encouraged to pursue across their entire lives. This desire to study hard texts in Aramaic, pre-modern Hebrew and other languages has led to a uniquely productive relationship between Torah and computing. Some of Israel’s very first computers were conscripted to digitize the canon and then make it easily searchable, and the number of digital tools currently available to consumers is remarkable. Today, vast numbers of religious texts are freely available online, alongside many translations and easy hyperlinks to navigate this deeply intertextual corpus.

The application of AI to Jewish learning is likely imminent. Generative AI already provides more-than-decent translations of even the most difficult texts, and it can be used to help learners navigate a large and unruly corpus with few obvious entry points. In the future, AI may also allow learners to converse directly with rabbis and books from centuries past.

At the same time, I suspect that the ritual aspect of Jewish learning will mean that AI enters the beit midrash (study hall) without entirely conquering it. The ability to read the Bible and Talmud in their original languages is likely to remain a cornerstone of text study, as is hevruta, the act of pouring over texts with a partner rather than alone in front of a screen. Jewish learning also emphasizes the interplay between scholars and their interpreters; AI models, meanwhile, often struggle to explain why they know what they know. Most importantly, Torah learning emphasizes that sacred texts are often multivalent, multilayered, and enigmatic. This way of viewing texts is hard to coax out of AI models that are mostly designed to provide concise and ostensibly complete interpretations of source material.

In practice, I suspect this means that AI will become another in a line of technologies that have enriched Jewish learning while leaving its predecessors intact. The modern beit midrash contains handwritten scrolls, bound books, and computer screens. Each has a place, and learners shuttle between them as needed. It’s easy to imagine AI joining the mix.

AI and Jewish Theology

AI has long inspired religious sentiments in people. Sometimes this is because models, which are both powerful and imperfectly understand, come across as godlike. Sometimes it’s through “the singularity,” already a quasi-messianic concept. Sometimes it is because the act of creating something in our image is reminiscent of the divine act of creation.

For monotheists, this last sentiment is powerful but hard to think through to its conclusions. If creating an AI is like creating a person—if the creation of a new form of life recapitulates a divine act—that would seem to make us gods. In fact, Yuval Noah Harari and others use this exact language to talk about the trajectory of technological development. Is it possible to understand AI as humanity’s offspring and avoid this language?

The answer, I think, is no. AI demands nothing less than a radical rethinking of Jewish theology as a sort of precedent, in which the long history of God’s relationship with humanity is re-examined in light of our present experience of creating something in our image. Both AI-as-God and AI-as-humanity’s-child contain notes of potential heresy, but the former is by far more ethically and religiously dangerous. I think the choice here is clear.

Crucial to this parallel is that both humanity and AI generate extreme concern on the mind of the creator that their progeny will go off the rails, that its “code” (in both senses of the term) is insufficiently clear. This concern—which for developers is called “the alignment problem” and for Jews is called “all of history”—should generate sympathy for God among the religious. Even if you believe that God is perfect, it’s very clear that there’s no such thing as perfect code; the Hebrew Bible itself contains endless examples of how human beings repeatedly struggle to do what is right long after the revelation at Sinai. It should also, I hope, evoke real trepidation in those who develop AI systems. AI isn’t just another new technology; it’s a technology that has the potential to define who we are as a species.

Convergence or divergence?

Does the above define a uniquely “Jewish perspective” on AI?

Of course not. Judaism is a decentralized religion and most Jewish leaders (like most religious leaders) don’t understand the tech well enough to have an informed position. The process of spreading AI literacy and then generating consensus is going to take a while. But while the world’s religions will largely converge on how to think about AI—just as they have on the need to protect the climate—I think they will remain distinct in important ways. Those distinctions may seem small now, but—as with the Jewish decision to retain handwritten Torah scrolls in the face of the printed book, or the choice not to use electricity on the Sabbath—they may end up becoming defining characteristics of the religion. Religious thinkers of all faiths should keep this in mind as they formulate their approaches.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Guest post, Philosophy, Religion

The Impact of AI in Education: Navigating the Imminent Future

A Buddhist Perspective on AI: Cultivating freedom of attention and true diversity in an AI future

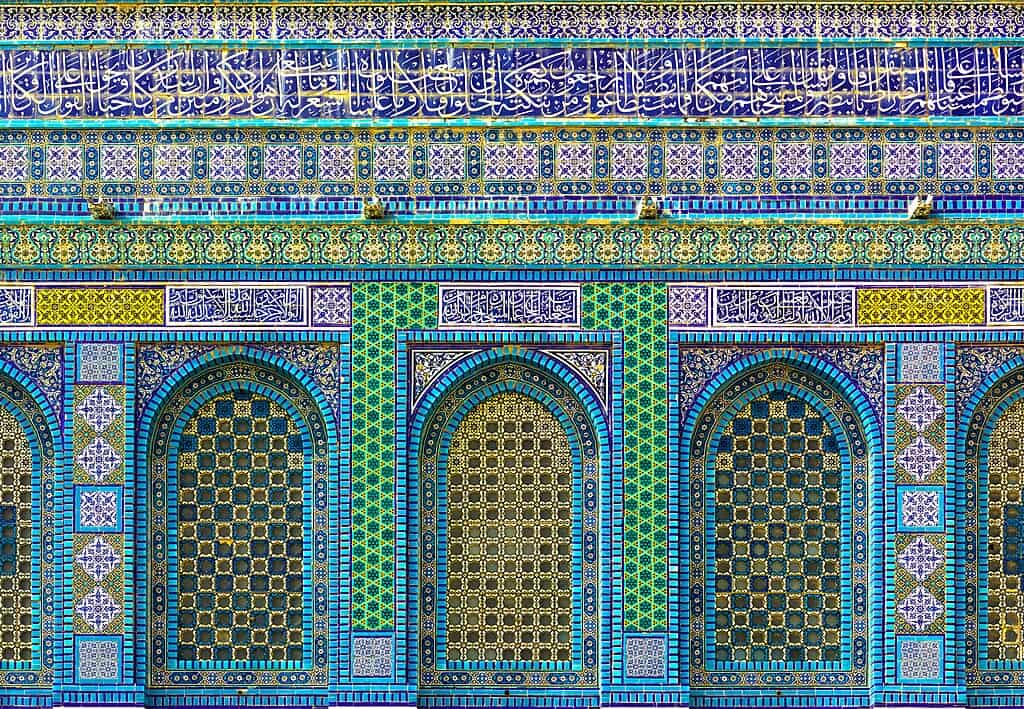

The Future and the Artificial: An Islamic Perspective

Some of our Futures projects

Control Inversion