North Korea’s Nuclear Test

Contents

North Korea claims that, on January 6, they successfully tested their first hydrogen bomb. Seismic analysis indicates that they did, in fact, test what was likely a nuclear bomb, but experts – and now the White House — dispute whether it was a real hydrogen bomb.

David Wright, Co-director of the Global Security Program for the Union of Concerned Scientists, said, “They are claiming that it was a hydrogen test, and as far as I can tell, nobody believes it was a real, two-stage hydrogen bomb, which is the staple of the US and Russian and Chinese arsenals.”

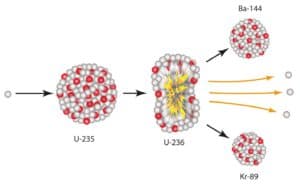

This is the fourth nuclear test North Korea has conducted since 2006. The first three are suspected to have been atomic bombs, more similar to those used on Japan during World War II. The power from an atomic bomb comes from the uranium or plutonium molecules splitting apart in a process known as fission, and the result for a first-generation bomb is a yield that’s on the order of about 10-20 kilotons. This is consistent with the estimated yields of the first three nuclear tests North Korea conducted.

When a hydrogen bomb explodes, the atoms within fuse together, and the resulting yield can be significantly more powerful than that of a fission bomb — a fission bomb is actually used to ignite a hydrogen bomb. If the explosion on January 6 were a true hydrogen bomb, the resulting yield would have been about 1,000 times larger than the North’s earlier three tests.

“It appears from the numbers I’ve seen that the yield is very similar to what their recent yields were, maybe 5-10 kilotons, which, if that number holds up, is probably too small to be a true hydrogen bomb,” Wright explained.

But Wright also pointed out that the North might simply be using the term, hydrogen bomb, somewhat differently than we do in the west. If tritium, which is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, is placed in the core of a standard uranium or plutonium atomic bomb, then when the bomb goes off, it will compress and ignite the tritium. In this case, the tritium fusion will emit a pulse of neutrons that will each trigger a fission reaction in the surrounding material, ensuring a more efficient use of the fissile explosives.

“It’s not what people typically mean by a hydrogen bomb,” Wright said, “but it does use some amount of fusion as a way of making the fission more effective. So that may have been what they did.”

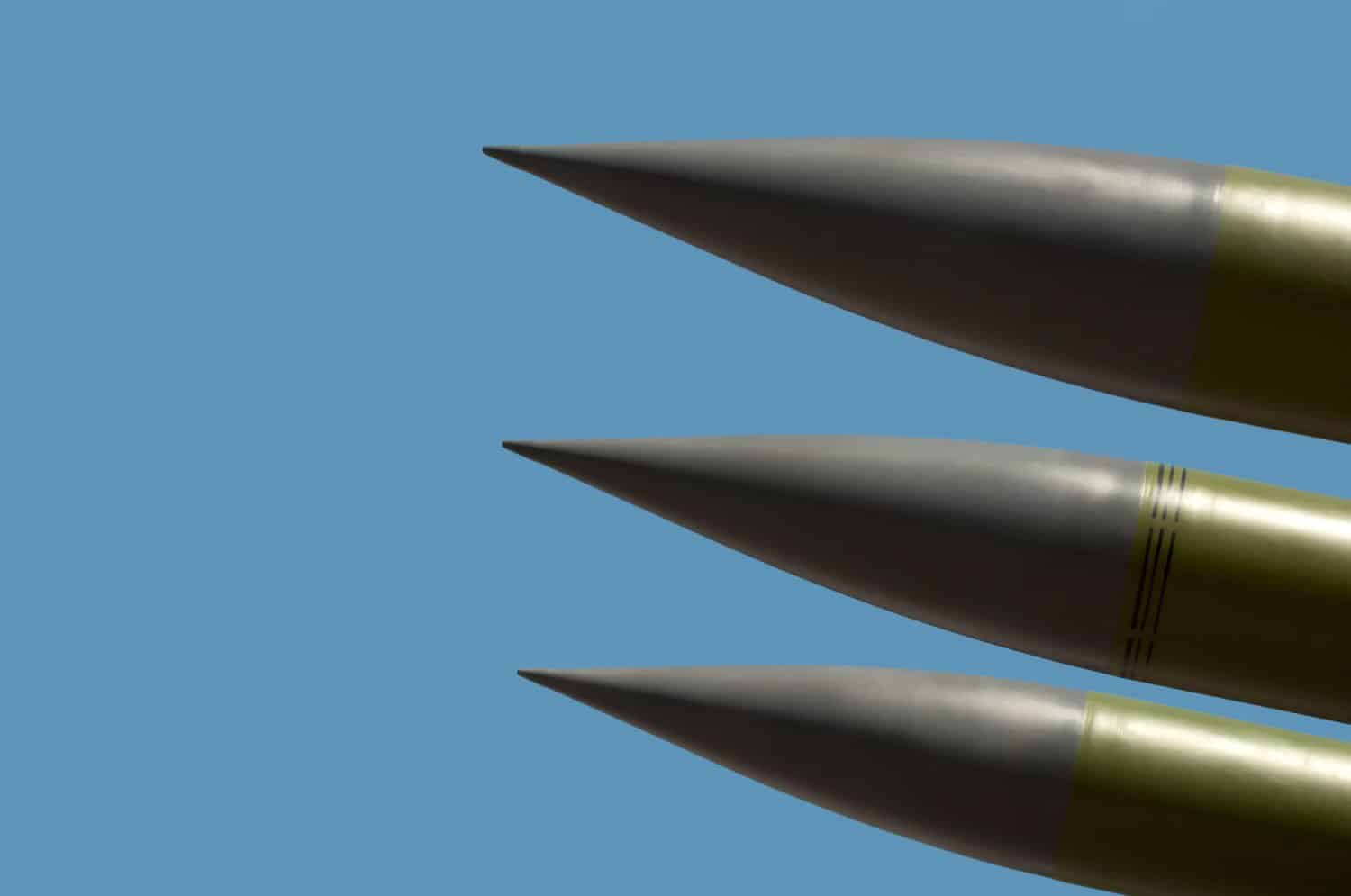

North Korea has also been developing their long-range missile system, and a smaller weapon like this could be more easily placed in a long-range missile than a full-sized, traditional hydrogen bomb.

However, as experts work to determine just what type of bomb the North tested, Wright argues there’s a more important fact to consider: It’s still a nuclear bomb. Whether it’s a fission bomb or a fusion bomb, he says, “It doesn’t really matter that much, to the extent that you’re still talking about nuclear weapons. If you develop a way to deliver them to a city, you’re talking catastrophe.”

To learn more about North Korea’s nuclear test, we recommend the following articles:

“North Korea nuclear: State claims first hydrogen bomb test,” by the BBC.

“Timeline: How North Korea went nuclear,” by CNN.

“Why is North Korea’s ‘hydrogen bomb’ test such a big deal?,” by the Washington Post.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Nuclear, Recent News

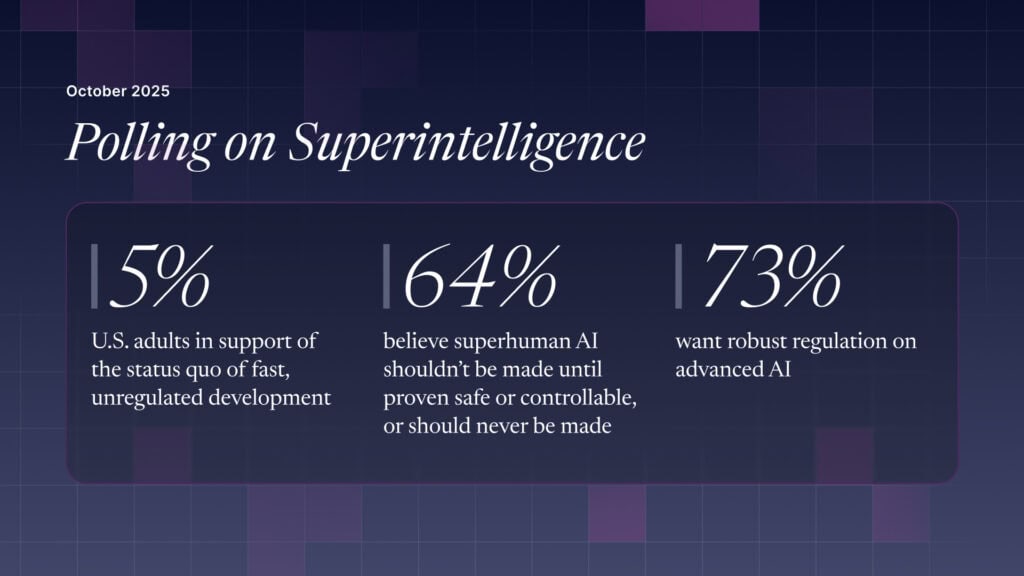

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI

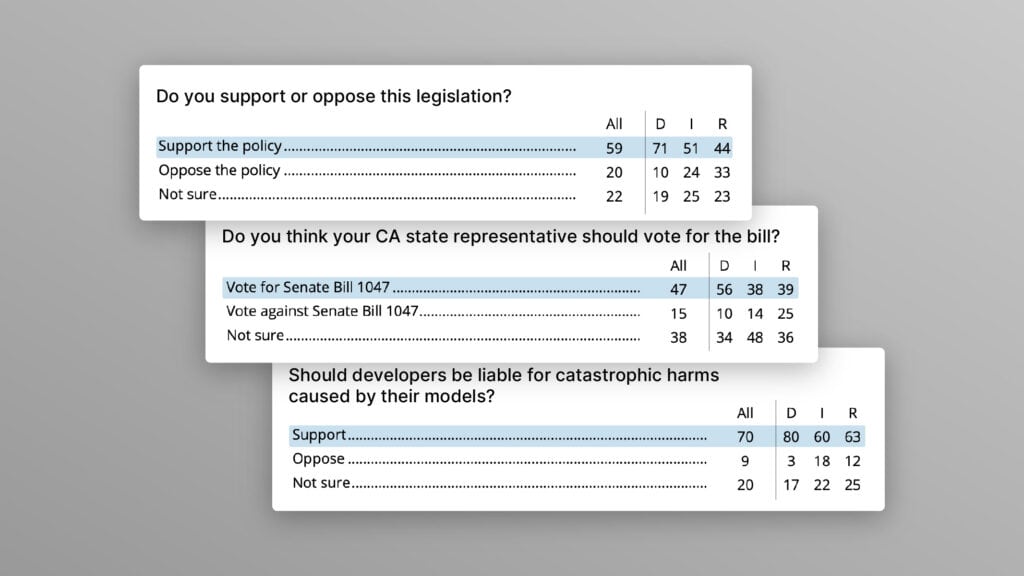

Poll Shows Broad Popularity of CA SB1047 to Regulate AI