Understanding the Risks and Limitations of North Korea’s Nuclear Program

Contents

Late last month, North Korea launched a ballistic missile test whose trajectory arced over Japan. And this past weekend, Pyongyang flaunted its nuclear capabilities with an underground test of what it claims was a hydrogen bomb: a more complicated—and powerful—alternative to the atomic bombs it has previously tested.

Though North Korea has launched rockets over its eastern neighbor twice before—in 1998 and 2009—those previous launches carried satellites, not warheads. And the reasoning behind those two previous launches was seemingly innocuous: eastern-directed launches use the earth’s spin to most effectively put a satellite in orbit. Since 2009, North Korea has taken to launching its satellites southward, sacrificing maximal launch conditions to keep the peace with Japan. This most recent launch, however, seemed intentionally designed to aggravate tensions not only with Japan but also with the U.S. And while there is no way to verify North Korea’s claim that it tested a hydrogen bomb, in such a tense environment the claim itself is enough to provoke Washington.

What We Know

In light of these and other recent developments, I spoke with Dr. David Wright, an expert on North Korean nuclear missiles at the Union of Concerned Scientists, to better understand the real risks associated with North Korea’s nuclear program. He described what he calls the “big question”: now that its missile program is advancing rapidly, can North Korea build good enough—that is, small enough, light enough, and rugged enough—nuclear weapons to be carried by these missiles?

Pyongyang has now successfully detonated nuclear weapons in six underground tests, but these tests have been carried out in ideal conditions, far from the reality of a ballistic launch. Wright and others believe that North Korea likely has warheads that can be delivered via short-range missiles that can reach South Korea or Japan. They have deployed such missiles for years. But it remains unclear whether North Korean warheads would be deliverable via long-range missiles.

Until last Monday’s launch, North Korea has sought to avoid provoking its neighbors by not conducting missile tests that would pass over other countries. Instead it has tested its missiles by shooting them upwards on highly lofted trajectories that land them in the Sea of Japan. This has caused some confusion about the range that North Korean missiles have achieved. Wright, however, uses height data from these launches to calculate the potential range that its missiles would reach on standard trajectories.

To date, North Korea’s farthest test launch—in July of this year—had the range to reach large cities in the U.S. mainland. That range, however, depends on the weight of the warhead used in the tests, a factor that remains unknown. Thus while North Korea is capable of launching missiles that would hit the U.S., it is unclear whether such missiles could actually deliver a nuclear warhead to that range.

A second key question, according to Wright, is one of numbers: how many missiles and warheads do the North Koreans have? Dr. Siegfried Hecker, former head of Los Alamos weapons laboratory, makes the following estimates based in part on visits he has made to North Korea’s Yongbyon laboratory. In terms of nuclear material, Hecker suggests that the North Koreans have “20 to 40 kilograms plutonium and 200 to 450 kilograms highly enriched uranium.” This material, he estimates, would “suffice for perhaps 20 to 25 nuclear weapons, not the 60 reported in the leaked intelligence estimate.” Based on past underground tests, it was estimated that the biggest yield of a North Korean warhead was about the size of the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima—which, though potentially devastating, is still about 20 times smaller than most U.S. warheads. The test this past weekend outsized its largest previous yield by a factor of five or more.

As for missiles, Wright says estimates suggest that North Korea may have a few hundred short- and medium-range missiles. The number of long-range missiles, however, is unknown—as is the speed with which new ones could be built. In the near term, Wright believes the number is likely to be small.

What seems clear is that Kim Jong Un, following his father’s death, began pouring money and resources into developing weapons technology and expertise. Since Kim Jong Un has taken power, the country’s rate of missile tests has skyrocketed: since last June, it has performed roughly 30 tests.

It has also unveiled a surprising number of new types of missiles. For years, the longest-range North Korean missiles reached about 1300 km—just putting Japan within range. In mid-May of this year, however, North Korea launched a missile with a potential range (depending on its payload) of more than 4000 km, for the first time putting Guam—which is 3500 km from North Korea—in reach. Then in July, that range increased again. The first launch in that month could reach 7000 km; the second—their current record—could travel more than 10,000 km, about the distance from North Korea to Chicago.

An Existential Risk?

On its own, the North Korean nuclear arsenal does not pose an existential risk—it is too small. According to Wright, the consequences of a North Korean nuclear strike, if successful, would be catastrophic—but not on an existential scale. He worries, though, about how the U.S. might respond. As Wright puts it, “When people start talking about using nuclear weapons, there’s a huge uncertainty about how countries will react.”

That said, the U.S. has overwhelming conventional military capabilities that could devastate North Korea. A nuclear response would not be necessary to neutralize any further threat from Pyongyang. But there are people who would argue that failure to launch a nuclear response would weaken deterrence. “I think,” says Wright, “that if North Korea launched a nuclear missile against its neighbors or the United States, there would be tremendous pressure to respond with nuclear weapons.”

Wright notes that moments of crisis have been shown to produce unpredictable responses: “There would be no reason for the U.S. to use nuclear weapons, but there is evidence to suggest that in high pressure situations, people don’t always think these things through. For example, we know that there have been war simulations that the U.S. has done where the adversary using anti-satellite weapons against the United States has led to the U.S. using nuclear weapons.”

Wright also worries about accidents, errors, and misinterpretations. While North Korea does not have the ability to detect launches or incoming missiles, it does have a lot of anti-aircraft radar. Wright offers the following example of a misinterpretation that could stem from North Korean detection of U.S. aircraft.

The U.S. has repeatedly said that it is keeping all options on the table—including a nuclear strike. It also talks about preemptive military strikes against North Korean launch sites and support areas, which would include targets in the Pyongyang area. North Korea knows this.

The aircraft that it would use in such a strike are likely its B-1 bombers. The B-1 once carried nuclear weapons but, per a treaty with Russia, has been modified to rid it of its nuclear capabilities. Despite U.S. attempts to emphasize this fact, however, Wright says that “statements we’ve seen from North Korea make you wonder whether it really has confidence that the B-1s haven’t been re-modified to carry nuclear weapons again”; the North Koreans, for example, repeatedly refer to the B-1 as nuclear-capable.

Now imagine that U.S. intelligence detects launch preparations of several North Korean missiles. The U.S. interprets this as the precursor to a launch toward Guam, which North Korea has previously threatened. The U.S. then sends a conventional preemptive strike to destroy those missiles using B-1s. In such a crisis, Wright reminds us, “Tensions are very high, people are making worst-case assumptions, they’re making fast decisions, and they’re worried about being caught by surprise.” It is feasible that, having detected the incoming B-1 bombers flying toward Pyongyang, North Korea would assume them to be carrying nuclear weapons. Under this assumption, they might fire short-range ballistic missiles at South Korea. This illustrates how misinterpretations might drive a crisis.

“Presumably,” says Wright, “the U.S. understands the risk of military attacks and such a scenario is unlikely.” He remains hopeful that “the two sides will find a way to step back from the brink.”

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Nuclear, Recent News

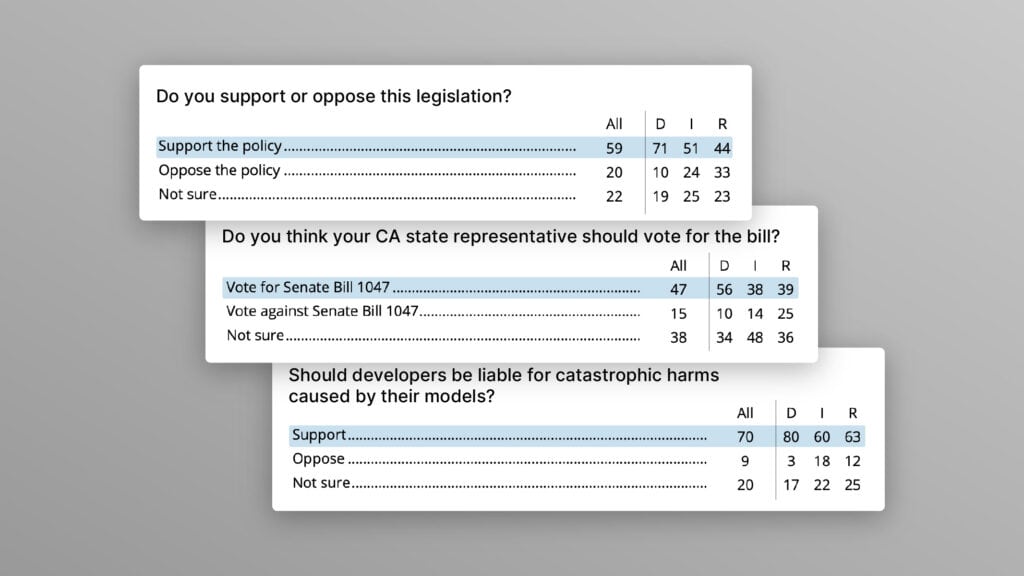

Poll Shows Broad Popularity of CA SB1047 to Regulate AI

FLI Praises AI Whistleblowers While Calling for Stronger Protections and Regulation