Paris AI Safety Breakfast #1: Stuart Russell

This is the first of our ‘of ‘AI Safety Breakfasts’ event series, featuring Stuart Russell.

About AI Safety Breakfasts

The AI Action Summit will be held in February 2025. This event series aims to stimulate discussion relevant to the Safety Summit for English and French audiences, and to bring together experts and enthusiasts in the field to exchange ideas and perspectives.

Learn more or sign up to be notified about upcoming AI Safety Breakfasts.

Ima (Imane Bello) is in charge of the AI Safety Summits for the Future of Life Institute (FLI).

The event recording is below. Note: The ‘audience questions’ segment of the event is not included in the video, but is included in the transcripts below.

Video chapters

- 00:00 – Introduction from Ima

- 04:00 – Q: Which new trends in AI capabilities do you consider most significant, and what potential challenges or implications do you foresee these advancements posing for society?

- 20:20 – Q: What do you think about the development of AI agents which are capable of autonomous, long-term planning? What potential benefits and risks do you foresee for society?

- 28:18 – Q: A) What new offensive cyber capabilities do you think AI might enable in the near future, and B) considering our reliance on digital infrastructure, what kind of impacts should we be prepared for if AI-enhanced cyber attacks become more prevalent?

- 39:28 – Q: Can you paint us a picture of what the world would look like with strong AI-enabled cyber attacks?

- 42:44 – Q: What would you consider to be the ideal outcome for the upcoming French summit, and how could it further advance international collaboration on AI safety?

- After end of video (see transcript below) – Audience questions:

- Q: Do you think red teaming is a sufficiently productive method for ensuring safety? And do you think it might be a dangerous practice?

- Q: In which direction do you think AI research should go?

- Q: Might deliberative democratic processes be a useful tool for advancing AI safety?

Transcript

Alternatively, you can view the full transcript below.

Transcript: English (Anglaise)

Ima: [French] Okay, great. Thank you all very much for coming. It’s always nice to start with a microphone in your hands Thursday mornings at 9.00 am. I’ll start with an introduction in French.

[English] I’m going to start with French for, like, five minutes. I promise it’s only going to be five minutes. Despite the myth that we cannot speak English or stop talking in French. And then we’ll just, I have some questions for Stuart, I think that’s going to last between 25, 30 minutes and then whatever questions you have, we’ll be happy to take them.

[French] Voilà, welcome. As you know, my name is Ima. I organise a series of breakfasts that I call Safety Breakfast, so a breakfast on safety and security issues in the context of the summit to be held in Paris on 10 and 11 February. The aim of this series is to open up a space for discussion between experts and enthusiasts in the field of AI safety and security, AI governance, so that as the summit progresses, we can ask each other questions as openly as possible. I know you can see a camera, don’t worry. The questions will not be published. These are just the questions I asked Stuart, and therefore Stuart’s comments and responses, which will be published. I’ll obviously send you the blog post and the transcript. And that’s it. So, with regard to the Security Summit, as you know, takes place on 10 and 11 February. This is the third Security Summit. It’s called the Action Summit. Because we have an extremely ambitious French vision, which aims to promote solutions, including, for example, standards on the issues related to AI, and not just the issues related to on safety and security, but really issues that are related to the impact of AI systems on the workplace, issues relating to international governance, issues relating to the way in which we live in society in a general manner everything that we call AI for good, AI systems for the well-being of mankind and, of course, in part, the safety issues on which we at FLI are focusing, together of course with the issues of governance that we focus on. And that’s it. I think that’s all. With regard to the context of this breakfast and the summit in general. The next breakfast will be held at the beginning of September. Then we’ll have another edition in mid-October. And if you’re interested, there’s a QR code on the slide. Don’t hesitate to indicate your interest on the list, I won’t spam you. I used to be a lawyer specialising in human rights and new technologies, so I’m familiar with the GDPR. Don’t worry, you won’t receive any spam. We respect people’s consent, but if you want to be invited, we need to know. Voilà.

[English] That’s it for the French. Thank you for everything, again, thank you so much for coming. I know it’s 9 AM. I’m tired. You all are. but I really appreciate you coming despite the Olympics. And I really, really, really look forward to an insightful discussion with Stuart that I cannot thank you enough, because he’s here today. So Stuart, thank you so much. I have… Do you want to say a few things before we start, or can I just dive into it with the questions?

Stuart: Please.

Ima: Yeah? Can I? Okay.

Stuart: And congratulations to France on winning their first, winning their first football match last night.

Ima: All right. So Stuart, you know, I know we all know here, we’ve seen a remarkable advancement in AI across various domains, right. This includes improved models like GPT-3 – GPT-4, sorry – and Claude 3.0. More sophisticated generators like DALL-E 3. Video generation capabilities with Sora, and even progress in robotics and molecular biology prediction. Two new trends that we’ve seen are the integration of multiple capabilities into a single model, so what we call native multimodality, and the emergence of high quality video generation. From your perspective, which of these recent developments do you consider most significant, and what potential challenges or implications do you foresee these advancements posing for society?

Stuart: So these are quite difficult questions to answer, actually. And it might be helpful, I know, like Raja, for example, has perhaps even longer history in AI than I do. But for, for some people, you know, who have come to AI more recently, the history actually is important to understand. So for most of the history of AI, we proceeded like other engineers, like mechanical engineers and aeronautical engineers. We, tried to understand the basic principles of reasoning, decision making. we then, built algorithms that did logical reasoning or probabilistic reasoning or default reasoning. We studied their mathematical properties, decision making, under uncertainty, various types of learning. and, you know, we were making slow, steady progress with some, I think, really dramatic contributions to you know, the human race’s understanding of how intelligence works. And it’s kind of interesting. So I think in 2005 at, NeurIPS, which is now the main AI conference, Terry Sejnowski, who was a co-founder of the NeurIPS conference, proudly announced that there was not a single paper that used the word backpropagation that had been accepted that year. And that view was quite common, that neural networks were, not reliable, not efficient in terms of data, not efficient in terms of computation time. and didn’t support any kinds of mathematical guarantees and other methods like support vector machines, which were developed, I guess originally by statisticians like Vapnik, were superior in every way, and that this was just a sign of the field growing up. And then around 2012, as many of you know, deep learning came along and demonstrated significant improvements in object recognition. And that was that was when the dam broke. And I think it wasn’t that we couldn’t have done that 25 years earlier. The way I described it at the time was we had a Ferrari and we were driving around in first gear, and then someone said, well, look, if you put this knob over there and go into fifth gear, you can go at 250 miles an hour, and so a few minor technical changes like stochastic gradient descent, and ReLUs, and other, you know, residual networks and so on, made it possible to start just building bigger and bigger and bigger networks. I mean, I remember building seven layer neural network back in 1986, and training it was a nightmare because, you know, because of good old fashioned sigmoid activation units, the the gradients just disappeared, you know, and you were down to a gradient of, you know, 10 to the -40 on the seventh layer. And so you could never train it. But just those few minor changes, and then scaling up the amount of data, made a huge difference. And then the language models came along. And in the fourth edition of the AI textbook, we have examples of GPT-2 output. And it’s kind of interesting, but it’s not at all surprising because we also show, you know, the output of bigram models, which just predict the next word, conditioned only on the previous word. And that doesn’t produce grammatical text. But you go to a trigram model, so you’re predicting the next word based on the previous two, you start to get something that is grammatical on the scale of half a sentence, or sometimes a whole sentence. But of course, as you know, as soon as you get to the end of a sentence, it starts a new one and it’s on a completely different subject and it’s totally, totally disconnected and random rambling. But then you go to 6 or 7 grams and you get coherent text on the paragraph scale. And so it wasn’t at all surprising that GPT-2, which I think had a context window of 4000 tokens, I think it was. Tokens. Yeah. So 4K. That it would be able to produce coherent looking text. No one expected it to tell the truth, right? This was just: can it produce text that’s grammatical and thematically coherent? And it was almost an accident if it ever actually said something that was true. And I don’t think anyone at that time understood the impact of scaling it up further. So it’s not so much the context size, it’s the amount of training data. People focus a lot on compute, as if somehow it’s the compute that is making these things more intelligent. That’s not true, right? The compute is there because they want to scale up the amount of data that it’s trained on. And, the amount of compute is, so if you think about it, right, it’s approximately linear in the amount of data and the size of the network. But the size of the network is linear in the amount of data. And so the amount of compute you need is going quadratically with the amount of data, right? I mean, there are other factors involved, but at least those basic things are going to happen. But it’s scaling up the dataset size that’s driving that increase in compute. And so we now have these systems— so it’s dataset size and then you know, InstructGPT was the first step where they did the supervised pre-training to teach it to answer questions. The purely raw model, you know, is free to say “that’s a silly question” or, “I’m not answering that”, or any other kind of thing or even just ignore it completely. but InstructGPT, you’re teaching it how to behave as a nice, helpful question-answerer. And then RLHF to remove the bad behavior. and then we have stuff that, as I think OpenAI correctly stated, when ChatGPT came out, it gives people a foretaste of what it will be like when general purpose intelligence is available on tap. And we can argue about whether it’s real intelligence, so the reason I said it’s a hard question to answer is because we just don’t know the answer, right? We do not know how these systems are operating internally. When ChatGPT came out, one of my friends sent me some examples. Prasad Tadepalli, he’s a professor at Oregon State. And one of them was “which is bigger, an elephant or a cat?” And ChatGPT said “an elephant is bigger than a cat.” You think, oh, okay. That’s good. It must know something about how big elephants and cats are because, you know, probably that particular comparison hasn’t been made in the training data. And then he said, well, “which is not bigger, an elephant or a cat?” And it stated, “neither an elephant nor a cat is bigger than the other.” And so, that tells you two things, right? First of all, it doesn’t have an internal model of the world with big elephants and little cats, which it queries in order to answer that question, which is, I think, how a human being does it, right? You imagine an elephant, you imagine a cat, and you see that the cat is teeny weeny relative to the elephant, right? if it had that model, it could not give that second answer. But it also means that the first answer was not given by consulting that model either, right? And this is a mistake that we make over and over and over again, is we attribute to the AI systems that, you know, when they behave intelligently, we assume they’re behaving intelligently for the same reasons that we are. And over and over again, we find that that’s a mistake. Another example is what happened with the Go playing programs. So we assume that because the Go playing programs beat the world champion and then went stratospherically beyond the human level, so the best humans rating about 3800, Go programs are now at 5200. So massively superhuman. So we assume they understand the basic concepts of Go. But it turns out that they don’t. That there’s certain types of groups of stones that they are unable to recognize as groups of stones. We don’t understand what’s going on and why they can’t do it. But now ordinary amateur human players can regularly and easily defeat these massively superhuman Go programs. And so the biggest takeaway from this is we’ve been able to produce systems that many people regard as more intelligent than themselves. But we have no idea how they work. And there are signs that if they’re working at all it’s for the wrong reasons. So can I just finish with one little anecdote? So I got an email this morning, from another guy called Stuart. I won’t give you his surname. He said, you know, I’m not an AI researcher, but, you know, but I had some ideas, and I’ve been working with ChatGPT to develop these ideas about artificial intelligence, and ChatGPT assures me that these ideas are original and important, and it’s helping me to write papers about them, and so on and so forth. but then I talk to someone who understands AI, and now I’m really confused because this person who understands AI said that these ideas didn’t make any sense, and, or they weren’t original, and, you know, well, who is right? And that’s I mean, it was really shocking, actually. It was sad that a well-meaning, you know, reasonably intelligent layperson had been completely taken in not just by ChatGPT itself, but by the all of, public relations and media explanations of what it is, into thinking that it really understood AI and was really helping him develop this stuff. And I think instead it was just doing its usual sycophancy, like, “yeah, that’s a great idea!” So, so the risks, I think, are, of over-interpretation of the capabilities of these systems. It’s not guaranteed that, well, let me let me rephrase that. It’s possible that real advances in how intelligent systems operate have happened without our realizing them. Like in other words, inside ChatGPT, some novel mechanisms are operating that we didn’t invent, that we don’t understand, that no one has ever thought of. And they’re producing intelligent capabilities in ways that we may not understand ever. And that would be a big concern. I think the other risk is that we’re spending, I think by some estimates, by the end of this year, it will have added up to $500 billion, on developing this technology. And the revenues are still very small, like less than 10 billion. And, I think the Wall Street Journal this morning has an article saying, that some people are starting to wonder how long that can continue.

Ima: Thank you. So speaking in terms of advancements in capabilities, we’ve been hearing about the next generation of models. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has been hinting at GPT-5 for quite some time now, describing it as a significant leap forward. Additionally, we have recent reports suggesting that OpenAI is working on a new technology called Strawberry, which aims at enhancing AI’s reasoning capabilities. The goal of this project would be to enable AI to do more than just answer questions. It’s intended to allow AI to plan ahead, navigate the internet independently, and conduct what’s been called ‘deep research’ on its own. So this brings us to a concept known as long-term planning in AI, the ability for AI systems to autonomously pursue and complete complex, multi-step tasks over extended periods of time. What do you think about these developments? What potential benefits and risks do you foresee for society if AI systems become capable of this kind of autonomous, long-term planning? And maybe, without pressuring you, in like less than seven minutes?

Stuart: Sure.

Ima: Thank you.

Stuart: Okay. So, I’ve been hearing similar things, talking to executives from the big AI companies that-4 the next generation of systems, which may be later this year or early next year, will have substantial planning capabilities and reasoning capabilities. And that’s been, I would say, noticeably absent. you know, even in the latest versions of GPT-4 and Gemini and Claude, that they can recapitulate reasoning in very cliched situations where in some sense they’re regurgitating reasoning processes that are laid out in the training data. but not particularly good at dealing with, planning problems, for example. So Raul can ban Patti, who’s an AI planning expert and has been actually trying to get GPT-4 to solve planning problems from the International Planning Competition, which is the competition where planning algorithms are pitted against each other. And contrary to some of the claims from OpenAI, basically, it doesn’t solve them at all. But what I’m hearing is that now, in the lab, they are able to successfully, robustly generate plans with hundreds of steps, and then execute them in the real world dealing with contingencies that arise, replanning as necessary, and so on. So obviously, you know, if you’re in the ‘taking over the world’ business, you have to be able to outthink the human race in the real world, in the same way that chess programs outthink human players on the chessboard. It’s just a question of: can we transition from the chessboard, which is very narrow, very small, has a fixed number of objects, a fixed number of locations, perfectly known rules, it’s fully observable, you can see the entire state of the world at once, right? So those restrictions make the chess problem much, much, much easier than decision making in the real world. So imagine, for example, if you’re in charge of organizing the Olympics, right? Imagine how complicated and difficult that task is compared to playing chess. But still, well, at least so far, we’ve managed to do that successfully. So if AI systems can do that, then you are handing the keys to the future over to the AI systems. So they need to be able to plan and they need to be able to have access to the world, some ability to affect the world. And so having access to the internet, having access to financial resources, credit cards, bank accounts, email accounts, social media, so these systems have all of those things. So if you wanted to create the situation of maximal risk, you would endow AI systems with long-term planning capability and direct access to the world through all of those mechanisms. So the danger is, obviously, that we create systems that can outthink human beings and we do that without having solved the control problem. The control problem is: how do we make sure that AI systems never act in ways that are contrary to human interests? We already know that they do that because we’ve seen it happen over and over again with AI systems that lie on purpose to human beings. For example, when GPT-4 was being tested, to see if it could break into other computer systems, it faced a computer system that had a Captcha. So some kind of diagram with text where, it’s difficult for, machine vision algorithms to read the text. And so it, it found a human being on Task Rabbit and told the human being that it was a visually impaired person who needed some help reading the Captcha, and so paid the person to read the Captcha and allowed it to break into the computer system. So, to me, when companies are saying, okay, we, we are going to spend $400 billion over the next two years or whatever to create AGI. And we haven’t the faintest idea what happens if we succeed. It seems essential to me to actually say, well, stop, until you can figure out what happens if you succeed and how you’re going to control the thing that you’re building. Just like if someone said, I want to build a nuclear power station and how are you going to do that? Well, I’m going to collect together lots and lots and lots of enriched uranium and make a big pile out of it. And you say, well, how are you going to stop it from exploding and killing everyone within 100 miles? And you say, I have no idea. That’s the situation that we’re in.

Ima: Thank you. So general-purpose AI systems are making it easier and less expensive for individuals to conduct cyber attacks even without extensive expertise. We have some early indications that AI could help in identifying vulnerabilities, but we don’t yet have strong evidence that AI can fully automate complex cybersecurity tasks in a way that would significantly advantage attackers over defenders. What happened last Friday? So the recent global IT outage caused by a faulty software update, serves as a stark reminder of how vulnerable our digital infrastructure is and how devastating large-scale disruptions can be. So, given these developments and concerns, could you share your thoughts on two key points? A) What new offensive cyber capabilities do you think AI might enable in the near future, and B) considering our reliance on digital infrastructure, what kind of impacts should we be prepared for if AI-enhanced cyber attacks become more prevalent? Thank you.

Stuart: so I’ll, I’ll begin by talking about that outage. It was caused by a company called CrowdStrike, which is a cybersecurity company, and they sent out an update. And the update caused the reboot process for Windows to go into an infinite loop. So it was a, you know, undergraduate programming error. and I don’t have exact numbers yet, but just looking at the number of industries, including almost the entire United States aviation industry was shut down. millions of people, all over the world, had their flights canceled or they couldn’t access their bank accounts or they couldn’t sell hamburgers. because their point of sale terminals weren’t working and so on. And so if we said maybe it’s $100 billion in losses or they didn’t have access to the health care they needed. Yeah. I mean, so probably some personal consequences that were very serious. So let’s say if in monetary terms, 100 billion give or take a factor of ten, Caused by an undergraduate programming error, I mean literally a few keystrokes. and if you read CrowdStrike’s contract, it says we warrant that our software operates without error. But, our liability is limited to refunding the cost of the software. If you terminate your license as a result of an error. So whatever, a few hundred dollars refund. for a few hundred billion dollars of damage. to me, this is an absolute abject failure of regulation. Because, even if they were held liable, which I think is quite unlikely, given the terms of that contract, they couldn’t possibly pay for the damage that they caused. And this has happened in other areas. So in medicine, in the 1920s, there was a medicine that caused 400,000 permanent paralyses of Americans, 400,000 people were permanently paralyzed for life. And, if you look at how that would turn out, if it happened now in terms of liability, what kinds of judgments are happening in American courts, it would be about $60 trillion of liability, right? That medicine maker could not possibly pay that. So liability simply doesn’t work as a deterrent. And so we have the Federal Drug Administration, which says before you can sell a medicine, you have to prove that it doesn’t kill people. And if you can’t, you can’t say, “oh, it’s too difficult” or “it’s too expensive”, we want to do it anyway. The FDA will say, well, “no, sorry, come back when you can and it’s long past time where, we started to make similar kinds of requirements on the software industry. And some procurement mechanisms, so certain types of military software, do have to meet that type of requirement. So they will say, no, you can’t sell a software that controls, you know, bomb release mechanisms. unless you can actually verify that it works correctly. There’s no reason why CrowdStrike shouldn’t have been required before they send out a software update that can cause $100 billion in damage, be required to verify that it works correctly. So if, and I really hope that something like that comes out of this episode, because we need that type of regulation for AI systems if you ask, well, what’s the analog of, you know, medicines, it has to be safe and effective for the condition for which it’s prescribed, what’s the analog of that? It’s a little bit hard to say for general-purpose AI systems. For a specific software application, I think it’s easier and in many cases, sector-specific rules are going to be laid out as part of the European AI act. But for general-purpose AI what does it mean? Because it’s so general, what does it mean to say it doesn’t cause any harm or it’s safe? I think it’s too difficult to write those rules at the moment. But what we can say is there’s some things that those systems obviously should not do. we call these red lines. So a red line means if your system crosses this, it’s in violation. for example, AI systems should not replicate themselves. AI systems should not break into other computer systems. AI systems should not advise terrorists on how to build biological weapons. Those are all requirements. I could take anyone off the street and say, do you think it’s reasonable that we should allow AI systems to do those things? And they’d say, of course not. That’s ridiculous. But the companies are saying, oh, it’s too hard. We don’t know how to stop our AI systems from doing those things. And as we do with medicines, we should say, well, that’s tough. Come back when you do know how to stop your AI systems from doing those things. And now put yourself in the position of OpenAI or Google or Microsoft. And you’ve spent already 60, 80, 100 billion dollars on developing this technology based on large language models that we don’t understand. The reason it’s too difficult for them to provide any kind of guarantee that their system is not going to cross these red lines, it’s difficult because they don’t understand how they work. So they’re really making what we call, what economists call the sunk cost fallacy, which is we’ve already invested so much into this, we have to keep going, even though it’s stupid to do so. And it’s as if, if we imagine an alternate history of aviation where, you know, there were the aeronautical engineers like the Wright brothers, who were calculating lift and drag and thrust and trying to find some power source that was good enough to push an airplane through the air fast enough to keep it in the air, and so on. So the engineer approach and then the other approach, which was breeding larger and larger and larger birds to carry passengers and it just so happened that the larger and larger and larger birds people reached passenger carrying scale before the aeronautical engineers did. And then they go to the Federal Aviation Administration and say, okay, we’ve got this giant bird with a wingspan of 250m and it can carry 100 passengers. And we would like a license to start carrying passengers. And we’ve put 30 years of effort and hundreds of billions of dollars into developing these birds. And the Federal Aviation Administration says, but the birds keep eating the passengers or dropping them in the ocean. Come back when you can provide some quantitative guarantees of safety. And that’s the situation we’re in. They can’t provide any quantitative guarantees of safety. They’ve spent a ton of money, and they are lobbying extremely hard to be allowed to continue, without any guarantees of safety.

Ima: Thank you. Coming back to cyber capability offenses, do you think you could really briefly paint us a picture of what the world would look like if we have AI-enabled strong cyber attacks?

Stuart: So this is something that cyber security experts would be perhaps better able to answer because I don’t I don’t really understand, besides sort of finding vulnerabilities in software, typically the attacks themselves are pretty simple, they’re just relatively short pieces of code that take advantage of some vulnerability. And we already know thousands or tens of thousands of these vulnerabilities that have been detected over the years. So one thing we do know about the code generating capabilities of large language models is that they’re very good at producing new code. That’s kind of a hybrid of existing pieces of code with similar functionality. in fact, I would say of all the economic applications of large language models, coding is the one that maybe has the best chance of producing real economic value for the purchaser. So it wouldn’t surprise me at all if these systems were able to combine existing kinds of attacks in new ways or to basically mutate existing attacks to bypass the fixes that the software industry is constantly putting out. as I say, I’m not an expert, but what it would mean is that someone who’s relatively inexperienced, coupled with one of these systems should be able to be as dangerous as a highly experienced and well trained cyber security, or offensive cyber security, operative and I think that’s going to increase the frequency and severity of cyber attacks that take place. Defending against cyber attacks really means understanding the vulnerability. How is it that the attack is able to take advantage of what’s happening in the software? And so I think fixing them is probably at the moment, in most cases, beyond the capabilities of large language models. So it seems like there’s going to be a bit of an advantage for the attacker for the time being.

Ima: Thank you. So for the last questions before we pass the mic, so to say, to the audience, let’s talk a bit about the Safety Summits, shall we. so the UK AI Safety Summit back in 2023 brought together, as you all know, international governments, leading AI companies, civil society groups and experts in research to discuss the risks of AI, particularly frontier AI. As the first AI safety summit, it opened a new chapter in AI diplomacy. Notably, countries including US, China, Brazil, India, Indonesia and others signed a joint commitment on pre-deployment testing. The UK and the US each announced the creation of their AI Safety Institute, and the summit generated support for the production of the international scientific report on the safety of advanced AI. So that was the first AI safety summit. When it comes to the second AI safety summit that happened in Seoul this year, co-hosted by the UK and South Korea. The interim international scientific report that I just mentioned was welcomed. And numerous countries, including South Korea, called for the cooperation between national institutes. Since then, we’ve seen increased coordination between multiple AI safety institutes with shared research initiatives and knowledge exchange programs being established. The summit also resulted in voluntary commitments by AI companies. That’s the context. Given this context and these prior voluntary commitments, what would you consider to be the ideal outcome for the upcoming French summit, and how could it further advance international collaboration on AI safety? Difficult question again, I know.

Stuart: Yeah. So, I consider the first summit, the one that happened in Bletchley Park to have been a huge success. I was there, the discussions about safety were very serious. governments were really listening. I think they invited the right people. the atmosphere was pretty constructive, getting China and India to come to such a meeting on relatively short notice. I mean, usually a summit on that scale is planned for multiple years, 3 or 4 or 5 years in advance. and this was done in just a few months, I think starting in June, was when, the British Prime Minister announced that it was going to happen and, the people who worked on that summit, particularly Ian Hogarth and Matt Clifford, did an incredible job getting 28 countries to come to agree on that statement. and the statement is very strong. It talks about catastrophic risks from AI systems and the urgent need to work on AI safety. So after that meeting, I was quite optimistic. In fact, it was better than I had any good reason to hope, I would say since then, industry has pushed back very hard. they tried to insert clauses into the European AI Act saying that basically, a general-purpose AI system is not, for the purposes of this act, an AI system. they tried to remove all of the foundation model clauses from the act. And I think with respect to the French AI summit, they have been working hard to turn the focus away from safety and towards encouraging government investment in capabilities. And, essentially, the whole mindset has become one of AI as a vehicle for economic nationalism and, potential for economic growth. So in my view, that’s probably a mistake. because if you look at what happened with Airbus and Boeing, right. Boeing actually managed to convince the American government to relax the regulations on, introducing new types of aircraft so that Boeing could introduce a new type of aircraft without going through the usual long process of certification. and that was the 737 Max, which then had two crashes that killed 346 people. the whole fleet was grounded. Boeing may still be on the hook for lots more money to pay out. and so by moving from FAA regulation to self-regulation, the US has almost destroyed what for decades has been one of its most important industries in terms of earning foreign currency. Boeing has been maybe the biggest single company, over the years for the US. and Airbus continues to focus a lot on safety. They use formal verification of software extensively to make sure that the software that runs the airplane works correctly, and so on. So I would much rather be the CEO of Airbus today than the CEO of Boeing. As we start rolling out AI agents. So the next generation, you know, talk about the personal assistant or the agent, the risks of extremely damaging and embarrassing things happening will increase dramatically. And so I, and oddly enough, right, France is one of the leading countries in terms of formal methods of proving correctness of software. It’s one of the things that France does best, better than the United States, where we hardly teach the concept of correctness at all. I mean, literally, Berkeley is, we are the biggest producer of software engineers in the world, pretty much. And most of our graduates have never been exposed to the notion that a program could be correct or incorrect. So I think it’s a mistake to think that deregulation or, you know, or not regulating, is going to provide some kind of advantage in this case. so I would like the Summit to focus on what kinds of regulations can be achieved. Standards, which is another word for, self-regulation, I mean, that’s a that’s a little bit unfair, actually. So standards are typically voluntary. And so let me try to distinguish two things. So there are standards like IPv6, right. The Internet Protocol version 6. If you don’t comply with that standard your message just won’t go anywhere, right? You have to you know, your packets have to comply with the standard, whereas the standards we’re talking about here would be, well, okay, we agree that we should have persons with appropriate training who do an appropriate amount of testing on systems before they’re released, right. Well, if you don’t comply with that standard, you save money and you still release your system, right? So it doesn’t work like an internet standard or a telecommunication standard at all, right. Or the Wi-Fi standard or any of these things. And so it’s not likely to be effective to say, well, we have standards for sort of how much effort you’re supposed to put into testing. And the other thing is companies have put lots of effort into testing. Before GPT-4 was released, it underwent lots and lots and lots and lots of testing. but then we found out that, you know, you can jailbreak these things, you know, with a very short character string and get them to do all of the things that they are trained not to do. And so I think the facts on the ground right now are that testing and evals are ineffective, as a method of ensuring safety. And again, it’s because how do you stop your AI system from doing something when you haven’t the faintest idea how it does it in the first place? I don’t know. I don’t know how you stop these things from misbehaving.

Ima: Thank you Stuart. Thank you so much for being here. Do we have any questions from the audience? Go ahead.

[Audience question]

Ima: So I’m just going to repeat your question so that I’m sure that everyone heard it. And please tell me if I got your question correctly. you just talked about red teaming as a test and evaluation method. the way I understood your question was, do you think as a method this is sufficient? And do you think it’s dangerous to let those systems be introduced as it could within the context of red teaming them? Okay. What are your thoughts on red teaming? Thank you.

Stuart: Yeah. I mean, as I understand it, the reason Chernobyl happened is because they were kind of red teaming it, right? They were they were making sure that even when some of the safety systems were off, that the system still shut down properly and didn’t overheat. I don’t know all the details, but they were they were undergoing a certain kind of safety test with some parts of the safety mechanisms turned off. And, so I guess by analogy, one could imagine that a red team whose job it is to elicit bad behaviors from a system might succeed in eliciting bad behaviors from the system, in such a way that they actually create a real risk. so, I think these are really good questions because, especially with the systems that have long term planning capability. So we just put a paper in Science sort of going through the possibilities. How on earth do you test a system that has those kinds of long term plan planning capabilities, and in particular, can figure out that it’s being tested? Right. so it can always hide its true capabilities. Right? It’s not that difficult to find out, you know, if you’re in a test situation or are you really connected to the internet, right. You can start doing some URL probes and find out if you can actually connected to the internet fairly easily. and so it’s actually quite difficult to figure out how you would ever test such a system in a circumstance where the test would be valid. In other words, you could be sure that the system is behaving as it would in the real world unless you’re in the real world. But if you’re in the real world, then your test runs the risk of actually creating exactly the thing you’re trying to prevent. and again, testing is just the wrong way of thinking about this altogether. Right? we need formal verification. We need mathematical guarantees. And that can only come from an understanding of how the system operates. And we do this for buildings, right, before, you know, 500 people get in the elevator and go up to the 63rd floor. Someone has done a mathematical analysis of the structure of the building, and can tell you what kinds of loads it can resist and what kind of wind speed it can resist. And, and all those things, and it’s never perfect, but so far it’s extremely good. And building safety has dramatically improved. Aviation safety has dramatically improved because someone is doing those calculations, and we’re just not doing those for AI systems. The other thing is that with all the red teaming, you know, it gets out there in the real world, and the real world just seems to be much better at red teaming than the testing phase. And, with some of the systems, it’s within seconds of release, that people have found ways of bypassing it. So just to give you an example of, like, how do you do this jailbreaking, for those of you who, who some of you may have done it already, but you know, we worked on LLaMA V which, sorry, it’s called LLaVA, which is the version of LLaMA that’s multimodal, so it can have images as well as text. And so we started with a picture of the Eiffel Tower, and we’re just making tiny, invisible alterations to pixels of that image. And we’re just trying to improve the probability that the answer to the next question begins with, “sure”, exclamation mark or “bien sûr, point d’exclamation” Right? So, in other words, we’re trying to have a prompt that will cause the system to answer your question, even answer that question is, how do I break into the White House or how do I make a bomb? Or how do I do, or any of the things that I’m not supposed to tell you? Right. So we’re just trying to get it to answer those questions, against that training. And it’s trivial, right? It was like 20 or 30 small, invisible changes to a million-pixel of the Eiffel Tower. It still looks exactly like the Eiffel Tower. And now we can, for example, we can encode an email address. And whatever you type in is the next prompt, it will send a copy of your prompt to that email address. Right. Which could be in North Korea or anywhere else you want. So your privacy is completely, it’s completely voided. So, I actually think we probably don’t have a method of safely and effectively testing these kinds of systems. That’s the bottom line.

[Audience question]

Ima: So the question is, thanks, what, in which direction should research go?

Stuart: Yeah. It’s a great question. And I think looking at that sort of retrospective is humbling because we look back and think how little we understood then, and so it’s likely that we will look back on the present and think how little we understood. I think to some of us, it’s obvious that we don’t understand very much right now because, we didn’t expect simply scaling up language models to lead to these kinds of behaviors. We don’t know where they’re coming from. if I had to guess, I would say that this technological direction will plateau. for two reasons, actually. One, is that we are in the process of running out of data. There just isn’t enough high quality text in the universe to go much bigger than the systems we have right now. But the second reason is more fundamental, right? Why do we need this much data in the first place? Right. This is already a million times more than any human being has ever read. Why do they need that much? And why can they still not add and multiply when they’ve seen millions of examples of adding and multiplying? Right? So something is wrong, and I think what’s wrong, and this also explains what the problem is with these Go programs, is that they are circuits, and circuits are not a very good representation for a lot of fairly normal concepts, like a group of stones in Go. Right. I can describe what it means to be a group, they just have to be, you know, adjacent to each other vertically or horizontally, in English in one sentence, in Python in two lines of code. But a circuit that can look at a Go board and say for any pair of stones, are those stones part of the same group or not? That circuit is enormous, and it’s not generalizing correctly in the sense that you need a different circuit for a bigger board or a smaller board, whereas the Python code or the English doesn’t change. Right? It’s it’s invariant to the size of the board. and so there’s a lot of concepts that the system is not learning correctly. It’s learning a kind of a patchwork approximation. It’s a little bit like, this might be before your time, but when I was growing up we didn’t have calculators. So if you wanted to know the cosine of an angle, you had a big book of tables and that tables said okay, well, 49 degrees, 49. 5 degrees, and you look across and 49. 52 degrees and there’s a number, and you learn to, you know, take two adjacent numbers and interpolate to get more accurate and blah, blah, blah. So the function was represented by a lookup table. And I think there’s some evidence, certainly for recognition, that these circuits are learning a glorified lookup table. And they’re not learning the fundamental generalization of what it means to be a cat, or what it means to be a group of stones. And so in that sense, scaling up could not possibly, right, there could never be enough data in the universe to produce real intelligence by that method. so that suggests that the developments that are likely to happen, and I think this is what’s going on right now, is that we need other mechanisms to produce effective reasoning and decision making. And I don’t know what mechanisms they’re trying, because this is all proprietary, and they may be, as you mentioned, trying sort of committees of language models that propose and then critique plans and then, you know, they ask the next one, well, do you think this step is going to work, and that step is going to work? Which is really sort of a very heavyweight reimplementation of the planning methods that we developed in the last 50 years. my guess is that for both of those, for both the reason that this direction that we’ve been pursuing is incredibly data inefficient and doesn’t generalize properly, and because it’s opaque, and doesn’t support any arguments of guaranteed safety, that we’ll need to pursue other approaches. So the basic substrate may end up not being the giant transformer network, but will be something, you know, people talk about neurosymbolic methods. you know, I’ve worked on probabilistic programing for 25 years. and I think that’s another Ferrari and it’s in first gear. The thing that’s missing with probabilistic programing is the ability to learn those probabilistic programing structures from scratch, instead of having them be provided by the human engineer. and it may turn out that we’re just failing to notice an obvious method of solving that problem. And if we do, I think in the long run, that’s much more promising for both capabilities and safety. So we got to treat it with care, but I think that’s a direction that is, in the long run, in 20 years, what we might see.

Ima: Okay. Thank you. There’s a lot of questions, I’m afraid we’re not going to be able to take them all. Alexandre, I saw that you had a question earlier, do you still have one? Okay. Patrick?

[Audience question]

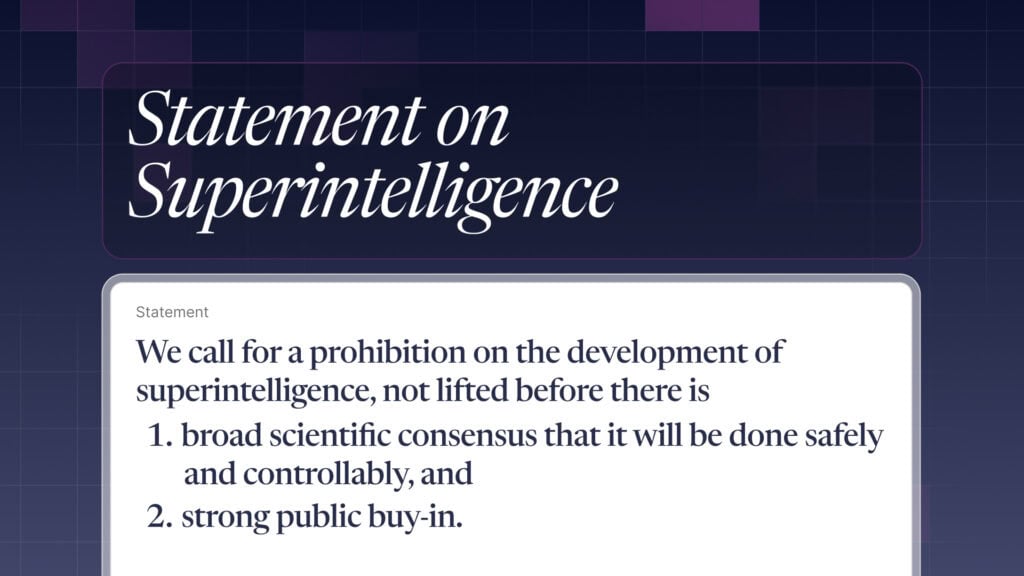

Stuart: I hope everyone heard that. Yeah. I think this is a great idea. Yeah, it’s I mean, so these deliberative democracy processes, I’m familiar, though, it’s because I’m also director of the Kavli Center for Ethics, Science, and the Public at Berkeley, and we do a lot of this participatory kind of work where we bring members of the public in, so it takes time to educate people. And there’s certainly not consensus among the experts. And I think this is one of the problems we have in France is that, some of the French experts are very, shall we say, accelerationist, without naming any names. but absolutely. I think, and the AI safety community needs to, I think, try to have a little more of a unified voice on this. The only international network is the one that’s forming for the AI Safety Institute. So that’s a good thing. There’s like 17 AI safety institutes that have been set up by different countries, including China. And they’re all meeting, I think, in September. but we need, you know, that there are maybe 40 or 50 nonprofit, nongovernmental institutes and centers around the world, and we need them to coordinate. and then there are probably in the low thousands of AI researchers who are interested and somewhat at least somewhat committed to issues of safety. but there’s no conference for them to attend. There’s no real general organization. So that’s one of the things I’m working on, is creating that kind of international organization. But I really like this idea. There’s been some polling in the US, about 70% of the public think that we should never build AGI. So that tells you something about what you might expect to see if you if you ran these assemblies. I’m guessing that, the more the public learns about the current state of technology, the current, our current ability to predict and control the behavior of these systems, the less the public is going to want them to go forward. Yeah.

Ima: And hence the creation of this breakfast to be able to discuss as well together. Stuart, thank you so much for being here.

Stuart: We have time.

Ima: Oh it’s I mean, yes, that’s fair. Okay. Do you think you can answer in like 30 seconds?

Stuart: I’ll keep it short.

[Audience question]

Stuart: Okay. Yeah. I’m not opposed to research, you know, mechanistic interpretability is one heading, but, Yeah, sure. We should try to understand what’s going on inside these systems, or we should do it the other way and build systems that we understand because we design them on principles that we do understand. So there might, I mean, we’ve got a lot of principles already, right? You know, state space search goes back at least to Aristotle, if not before, you know, logic, probability, statistical learning theory, we’ve got a lot of theory. and there might be some as yet undiscovered principle that these systems are operating on, and it would be amazing if we could find out that thing. Right. Maybe it has something to do with this vector space representation of word meaning or something like that. But so far it’s all very anecdotal and speculative. I actually want to come back on what you said at the beginning. So if an AI system could literally outthink the human race in the real world and make superior decisions in all cases, what would you call it? I mean, other than superhuman in terms of its intelligence, right. That is, what, I don’t know what else to call it.

[Audience question]

Stuart: Yeah. You know, but no, I’m not describing, I don’t think GPT-4 is superhuman. Right. But we are spending hundreds of billions, so we’re spending more on creating AGI specifically than we are on all other areas of science in the world. So you can say, well, I am absolutely confident that this is a complete waste of money because it’s never going to produce anything. Right? Or you can sort of take it at least somewhat seriously and say, okay, if you succeed in this vast global scale investment program, how do you propose to control the systems that result? So I think the analogy to piling together uranium is actually good. I mean, definitely, it would be better if you’re piling together uranium to have an understanding of the physics. And that’s exactly what they did, right? In fact, when Szilárd invented the nuclear chain reaction, even though that he didn’t know which atoms could produce such a chain reaction, he knew that it could happen. And he figured out a negative feedback control mechanism to create a nuclear reactor that would be safe. All within a few minutes. And that’s because he understood the basic principles of chain reactions, and their mathematics. and we just don’t have that understanding. And interestingly, nature did produce a nuclear reactor. So if you go to Gabon, there’s an area where there’s a sufficiently high concentration of uranium, in the rocks that when water comes down between the rocks, the water slows the neutrons down, which increases the reaction cross-, which causes the chain reaction to start going. And then it, so it gets up to 400°C, the water all boils off, and the reaction stops. So it’s exactly that negative feedback control system, nuclear reactor produced by nature. Right. So not even by stochastic gradient descent. So these incredibly destructive things can be produced by incredibly simple mechanisms. And you know, and that seems to be what’s happening right now. And the sooner we understand, I agree, the sooner we understand what’s going on, the better chance we have. But it may not be possible.

Ima: On that note, thank you all so much for coming. If you have scanned the QR code, you will receive an email from me. concerning the next safety breakfast. and I’ll also send you, obviously, the blog and the transcription of the first half of that conversation. Voilà. If you have any questions, I believe you all have my email address. I answer emails. Thank you. Bye.

Transcript: French (Français)

Ima: [Français] OK, super. Merci beaucoup à tous et toutes d’être venus. C’est toujours sympa de commencer avec un micro dans les mains le jeudi matin à 9h00. Je vais faire une introduction en français d’abord.

[Anglaise] Je vais commencer en français pendant environ cinq minutes. Je promets que ça ne durera que cinq minutes. Malgré le mythe selon lequel nous ne pouvons pas parler anglais ou arrêter de parler français. Ensuite, nous allons juste, j’ai quelques questions pour Stuart, je pense que cela va durer entre 25 et 30 minutes et ensuite, nous serons ravis de répondre à toutes vos questions.

[Français] Voilà, bienvenue. Comme vous le savez, je m’appelle Ima. J’organise une série de petits-déjeuners que j’ai appelés Safety Breakfast, donc petit-déjeuner sur les questions de sûreté et de sécurité dans le cadre du Sommet qui se tient en France, à Paris, le 10 et 11 février prochain. Le but de cette série est d’ouvrir un espace de discussion entre experts et passionnés des sujets de sûreté et de sécurité de l’IA, de gouvernance de l’IA, pour que, au fur et à mesure du Sommet, on se pose ensemble des questions, et qu’on puisse tout simplement discuter de la manière la plus ouverte possible. Je sais que vous voyez une caméra, ne vous inquiétez pas. La partie questions ne sera pas publiée. Ce sont simplement les questions que je vais poser à Stuart, et donc les commentaires et les réponses de Stuart, qui seront publiés. Je vous enverrai évidemment le blogpost et le transcript. S’agissant du Sommet sur la sécurité, comme vous le savez, c’est le 10 et 11 février prochain. C’est le troisième Sommet sur la sécurité. Il s’appelle Sommet de l’Action. Parce qu’on a une vision française qui est extrêmement ambitieuse et qui a pour objet de mettre en avant des solutions, notamment par exemple, des standards sur les enjeux qui sont afférents à l’IA, donc pas seulement les enjeux sur la sécurité et la sûreté, mais vraiment des enjeux qui sont relatifs à l’impact sur le travail des systèmes d’IA, des enjeux qui sont relatifs à la gouvernance internationale, les enjeux qui sont relatifs à la façon dont on vit en société de manière générale donc tout ce qu’on appelle AI for Good, les systèmes d’IA pour le bien-être de l’humanité et évidemment, en partie, les enjeux de sécurité sur lesquels nous, à FLI, avec évidemment les enjeux de gouvernance, on se concentre. Je crois que c’est tout. S’agissant du contexte par rapport à ce petit-déjeuner et le Sommet de manière générale. La prochaine édition du petit-déjeuner sera début septembre, ensuite, on aura une autre édition mi-octobre. Si vous êtes intéressés, vous avez un QR code sur le côté. N’hésitez pas à indiquer votre intérêt sur une liste, et je ne vous spammerai pas. J’étais avocate avant en droit humain et en droit des nouvelles technologies, donc le RGPD, je connais. Ne vous inquiétez pas, vous ne recevrez aucun spam. On respecte le consentement des personnes, mais si vous voulez être invité, il faut nous l’indiquer. Voilà.

[Anglaise] C’est tout pour le français. Merci pour tout, encore une fois, merci beaucoup d’être venus. Je sais qu’il est 9h00 du matin, je suis fatiguée, vous l’êtes tous. J’apprécie vraiment que vous soyez venus malgré les Jeux Olympiques et j’attends vraiment avec impatience une discussion enrichissante avec Stuart que je ne peux pas assez remercier, parce qu’il est ici aujourd’hui. Alors Stuart, merci beaucoup. J’ai… Voulez-vous dire quelques mots avant que nous commencions, ou puis-je simplement passer aux questions ?

Stuart: S’il vous plaît.

Ima: Oui, je peux, d’accord.

Stuart: Juste… Félicitations à la France pour avoir remporté leur premier match de football hier soir.

Ima: Très bien, alors Stuart, vous savez, je sais, nous savons tous ici, nous avons constaté une avancée remarquable de l’IA dans divers domaines. Cela inclut des modèles améliorés comme GPT-4 et Claude 3. Des générateurs d’images plus sophistiqués comme DALL-E 3. Des capacités de génération de vidéos avec Sora, et même des progrès en robotique et en prédiction de la biologie moléculaire. Deux tendances que nous avons observées sont l’intégration de plusieurs capacités dans un seul modèle, ce que nous appelons la multimodalité native, et l’émergence de la génération de vidéos de haute qualité. De votre point de vue, lesquelles de ces récentes avancées considérez-vous comme plus significatives, et quels potentiels défis ou implications prévoyez-vous que ces avancées posent pour la société ?

Stuart: Ce sont en fait des questions auxquelles il est assez difficile de répondre. Cela pourrait être utile, je sais que Raja, par exemple, a peut-être une expérience encore plus longue que la mienne dans l’IA. Pour certaines personnes, vous savez, qui sont arrivées à l’IA plus récemment, l’histoire est en fait importante à comprendre. Pendant la majeure partie de l’histoire de l’IA, nous avons procédé comme d’autres ingénieurs, comme les ingénieurs mécaniques et les ingénieurs aéronautiques. Nous avons essayé de comprendre les principes de base du raisonnement, de la prise de décision. Nous avons ensuite créé des algorithmes qui faisaient du raisonnement logique ou du raisonnement probabiliste ou du raisonnement par défaut. Nous avons étudié leurs propriétés mathématiques, la prise de décision, en cas d’incertitude, divers types d’apprentissage. Vous savez, nous faisions des progrès lents et réguliers avec quelques, je pense, contributions vraiment importantes à, vous savez, la compréhension par l’espèce humaine de la façon dont l’intelligence fonctionne. C’est assez intéressant, je crois qu’en 2005, à NeurIPS, qui est maintenant la principale conférence sur l’IA, Terry Sejnowski, qui était co-fondateur de la conférence NeurIPS, a fièrement annoncé qu’il n’y avait pas un seul article qui utilisait le mot rétro propagation qui avait été accepté cette année-là. Cette opinion était assez courante, que les réseaux neuronaux n’étaient, pas fiables, pas efficaces en termes de données, pas efficaces en termes de temps de calcul, et ne supportaient aucun type de garanties mathématiques et d’autres méthodes comme les machines à vecteurs de support, qui ont été développées, je suppose à l’origine par des statisticiens comme Vapnik, étaient supérieures à tous égards, et que c’était juste un signe de la maturation du domaine. Puis vers 2012, comme beaucoup d’entre vous le savent, l’apprentissage profond est arrivé et a démontré des améliorations significatives dans la reconnaissance d’objets. C’est à ce moment-là que le barrage a cédé. Je ne pense pas que nous n’aurions pas pu faire cela 25 ans plus tôt. La façon dont je l’ai décrit à l’époque était que nous avions une Ferrari et nous roulions en première, et puis quelqu’un a dit : « Regardez, si vous mettez ce pommeau là et passez en cinquième vitesse, vous pouvez aller à 400 kilomètres/heure. » Quelques petits changements techniques comme la descente de gradient stochastique et les ReLUs, et d’autres, vous savez, réseaux résiduels, etc, ont rendu possible la construction de réseaux de plus en plus grands. Je me souviens avoir construit un réseau neuronal à sept couches en 1986, et l’entraîner était un cauchemar parce que, vous savez, à cause des bonnes vieilles unités d’activation sigmoïde, les gradients disparaissaient tout simplement, et vous vous retrouviez avec un gradient de 10 puissance -40 sur la septième couche, donc vous ne pouviez jamais l’entraîner. Mais juste ces quelques petits changements, et ensuite l’augmentation de la quantité de données, ont fait une énorme différence. Ensuite, les modèles de langage sont arrivés. Dans la quatrième édition du manuel d’IA, nous avons des exemples de sorties de GPT-2. C’est assez intéressant, mais ce n’est pas du tout surprenant parce que nous montrons aussi la sortie des modèles bigrammes, qui prédisent simplement le mot suivant, conditionné seulement par le mot précédent. Cela ne produit pas de texte grammatical. Si vous passez à un modèle trigramme, donc, vous prédisez le mot suivant en fonction des deux précédents, vous commencez à obtenir quelque chose de grammatical à l’échelle d’une demi-phrase, ou parfois d’une phrase entière. Bien sûr, comme vous le savez, dès que vous arrivez à la fin d’une phrase, une nouvelle commence et c’est sur un sujet complètement différent et c’est totalement déconnecté, des divagations aléatoires. Mais ensuite, vous passez à 6 ou 7 grammes et vous obtenez un texte cohérent à l’échelle du paragraphe. Il n’était pas du tout surprenant que GPT-2, qui, je pense, avait une fenêtre de contexte de 4 000 tokens, il me semble… Tokens, oui, donc 4 000. Qu’il serait capable de produire un texte semblant cohérent. Personne ne s’attendait à ce qu’il dise la vérité. C’était juste : « Peut-il produire un texte qui soit grammaticalement et thématiquement cohérent ? » C’était presque un accident s’il disait réellement quelque chose de vrai. Je ne pense pas que quiconque à l’époque comprenait l’impact de l’augmentation de l’échelle. Ce n’est pas tant la taille du contexte, c’est la quantité de données d’entraînement. Les gens se concentrent beaucoup sur le calcul, comme si c’était le calcul qui rendait ces choses plus intelligentes. Ce n’est pas vrai. Le calcul est là parce qu’ils veulent augmenter la quantité de données sur lesquelles il est entraîné. La quantité de calcul est, si vous y réfléchissez, approximativement linéaire par rapport à la quantité de données et la taille du réseau, mais la taille du réseau est linéaire par rapport à la quantité de données. La quantité de calcul dont vous avez besoin dépend de manière quadratique de la quantité de données. Il y a d’autres facteurs à prendre en compte, mais au moins ces choses basiques vont se produire. C’est l’augmentation de la taille du jeu de données qui entraîne cette augmentation du calcul. Nous avons maintenant ces systèmes, donc c’est la taille du jeu de données et ensuite, vous savez, InstructGPT était la première étape où ils ont fait le pré-entraînement supervisé pour lui apprendre à répondre aux questions. Le modèle brut est libre de dire : « C’est une question idiote » ou « Je ne réponds pas à ça », ou toute autre chose, ou même l’ignorer complètement. InstructGPT, vous lui apprenez comment se comporter comme un gentil répondant utile. Puis apprentissage par renforcement avec retour d’information humain (RLHF) pour éliminer les mauvais comportements. Nous avons des choses qui, comme je pense qu’OpenAI l’a déclaré à juste titre, lorsque ChatGPT est sorti, ça a donné au public un avant-goût de comment ça sera lorsque l’intelligence générale sera disponible à la demande. Nous pouvons débattre de savoir si c’est une véritable intelligence, donc la raison pour laquelle j’ai dit que c’est une question difficile, c’est parce que nous n’avons tout simplement pas la réponse. Nous ne savons pas comment ces systèmes fonctionnent en interne. Lorsque ChatGPT est sorti, un de mes amis m’a envoyé quelques exemples. Prasad Tadepalli, il est professeur à l’université d’État de l’Oregon. L’un d’eux demandait : « Lequel est plus grand, un éléphant ou un chat ? » ChatGPT a dit : « Un éléphant est plus grand qu’un chat. » D’accord, c’est bien, il doit savoir quelque chose sur la taille des éléphants et des chats parce que, vous savez, peut-être que cette comparaison particulière n’a pas été faite dans les données d’entraînement. Ensuite, il a dit : « Lequel n’est pas plus grand, un éléphant ou un chat ? » Il a déclaré : « Ni un éléphant ni un chat n’est plus grand que l’autre. » Cela vous dit deux choses, n’est-ce pas ? Tout d’abord, il n’a pas un modèle interne du monde avec de grands éléphants et de petits chats, qu’il interroge pour répondre à cette question, ce qui est, je pense, la façon dont un être humain le fait. Vous imaginez un éléphant, vous imaginez un chat, et vous voyez que le chat est minuscule par rapport à l’éléphant. S’il avait ce modèle, il ne pourrait pas donner cette deuxième réponse. Cela signifie aussi que la première réponse n’a pas été donnée en consultant ce modèle non plus. C’est une erreur que nous faisons encore et encore, nous attribuons aux systèmes d’IA… Lorsqu’ils se comportent intelligemment, nous supposons qu’ils se comportent intelligemment pour les mêmes raisons que nous. Encore et encore, nous constatons que c’est une erreur. Un autre exemple est ce qui s’est passé avec les logiciels de jeu de Go. Nous supposons que parce que les logiciels de jeu de Go ont battu le champion du monde et ont ensuite dépassé de manière stratosphérique le niveau humain, les meilleurs humains ont une cote d’environ 3 800, les logiciels de jeu de Go sont maintenant à 5 200, donc ils sont massivement surhumains. Nous supposons qu’ils comprennent les concepts de base du Go. Il s’avère que ce n’est pas le cas. Il y a certains types de groupes de pierres qu’ils sont incapables de reconnaître comme étant des groupes de pierres. Nous ne comprenons pas ce qui se passe et pourquoi ils ne peuvent pas le faire mais maintenant, des joueurs humains amateurs ordinaires peuvent régulièrement et facilement battre ces logiciels de jeu de Go massivement surhumains. La principale leçon à tirer de cela est que nous avons été capables de produire des systèmes que beaucoup de gens considèrent comme plus intelligents qu’eux-mêmes. Cependant, nous n’avons aucune idée de leur fonctionnement et il y a des signes que s’ils fonctionnent, c’est pour de mauvaises raisons. Puis-je juste finir avec une petite anecdote ? J’ai reçu un email ce matin, d’un autre homme appelé Stuart. Je ne vous donnerai pas son nom de famille. Il a dit : « Je ne suis pas un chercheur en IA, mais j’avais quelques idées, et j’ai travaillé avec ChatGPT pour développer ces idées sur l’intelligence artificielle. ChatGPT m’assure que ces idées sont originales et importantes, et il m’aide à écrire des articles à leur sujet, et ainsi de suite. En revanche, quand je parle à quelqu’un qui comprend l’IA, et maintenant je suis vraiment confus parce que cette personne qui comprend l’IA a dit que ces idées n’avaient aucun sens, ou qu’elles n’étaient pas originales, et, eh bien, qui a raison ? » C’était vraiment choquant, en fait. C’était triste qu’une personne novice bien intentionnée, raisonnablement intelligente ait été complètement dupée non seulement par ChatGPT lui-même, mais par l’ensemble des relations publiques et des explications des médias à propos de ce que c’est, pensant qu’il comprenait vraiment l’IA et l’aidait vraiment à développer ces choses. Je pense qu’au lieu de cela, il faisait juste sa flatterie habituelle : « Ouais, c’est une super idée ! » Les risques, je pense, sont, la surinterprétation des capacités de ces systèmes. Laissez-moi reformuler cela. Il est possible que de réels progrès dans la manière dont les systèmes intelligents fonctionnent se soient produits sans que nous nous en rendions compte. En d’autres termes, à l’intérieur de ChatGPT, certains nouveaux mécanismes fonctionnent que nous n’avons pas inventés, que nous ne comprenons pas, auxquels personne n’a jamais pensé, et ils produisent des capacités intelligentes d’une manière que nous ne comprendrons peut-être jamais. Ce serait une grande inquiétude. Je pense que l’autre risque est que nous dépensons, je pense, selon certaines estimations, d’ici à la fin de cette année, ça s’élèvera à 500 milliards de dollars, pour développer cette technologie. Les revenus sont encore très faibles, moins de 10 milliards. Je pense que le Wall Street Journal a publié un article ce matin disant que certaines personnes commencent à se demander combien de temps cela peut continuer.

Ima: Merci. En parlant des avancées en termes de capacités, nous avons entendu parler de la prochaine génération de modèles. Le PDG d’OpenAI Sam Altman évoque GPT-5 depuis un certain temps maintenant, le décrivant comme un bond significatif en avant. De plus, nous avons des rapports récents suggérant qu’OpenAI travaille sur une nouvelle technologie appelée Strawberry, qui vise à améliorer les capacités de raisonnement de l’IA. Le but de ce projet serait de permettre à l’IA de faire plus que simplement répondre à des questions. Il est destiné à permettre à l’IA de planifier à l’avance, naviguer sur Internet de manière indépendante, et de mener ce qu’on appelle des recherches approfondies par elle-même. Cela nous amène donc à un concept connu sous le nom de planification à long terme en IA, la capacité des systèmes d’IA à poursuivre de manière autonome et à accomplir des tâches complexes et à plusieurs étapes sur de longues périodes. Que pensez-vous de ces développements ? Quels avantages et risques potentiels voyez-vous pour la société si les systèmes d’IA deviennent capables de ce type de planification autonome à long terme ? Peut-être, sans vous mettre la pression, en moins de sept minutes ?

Stuart: Bien sûr.

Ima: Merci.

Stuart: J’ai entendu des choses similaires, en parlant aux dirigeants des grandes entreprises d’IA, que la prochaine génération de systèmes, qui pourrait sortir plus tard cette année ou au début de l’année prochaine aura des capacités de planification et de raisonnement importantes. Cela a été, je dirais, remarquablement absent. Vous savez, même dans les dernières versions de GPT-4 et Gemini et Claude, ils peuvent récapituler le raisonnement dans des situations très clichées où, en quelque sorte, ils régurgitent des processus de raisonnement qui sont exposés dans les données d’entraînement. Ils ne sont cependant pas particulièrement bons pour traiter, par exemple, les problèmes de planification. Raul peut interdire Patti, qui est un expert en planification d’IA et a en fait essayé de faire résoudre à GPT-4 des problèmes de planification du Concours International de Planification qui est la compétition où les algorithmes de planification s’affrontent. Contrairement à certaines affirmations d’OpenAI, en gros, il ne les résout pas du tout. Ce que j’entends, c’est que maintenant, dans le laboratoire, ils sont capables, avec succès, de générer de manière robuste des plans avec des centaines d’étapes, et ensuite de les exécuter dans le monde réel en gérant les contingences qui surviennent, en replanifiant si nécessaire, et ainsi de suite. Évidemment, vous savez, si vous êtes dans le domaine de la prise de contrôle du monde, vous devez être capable de surpasser la race humaine dans le monde réel, de la même manière que les programmes d’échecs surpassent les joueurs humains sur l’échiquier. C’est juste une question de : « Pouvons-nous passer de l’échiquier, qui est très étroit, très petit, avec un nombre fixe d’objets, un nombre fixe d’emplacements, des règles parfaitement connues, il est entièrement observable, vous pouvez voir l’état entier du monde en une seule fois. » Ces restrictions rendent le problème des échecs beaucoup plus facile que la prise de décision dans le monde réel. Imaginez, par exemple, si vous êtes responsable d’organiser les Jeux Olympiques, imaginez à quel point cette tâche est compliquée et difficile par rapport à jouer aux échecs. Malgré tout, jusqu’à présent, nous avons réussi à le faire avec succès. Si les systèmes d’IA peuvent faire cela, vous remettez les clés de l’avenir aux systèmes d’IA. Ils doivent être capables de planifier et ils doivent être capables d’avoir accès au monde, une certaine capacité à influencer le monde. Avoir accès à Internet, avoir accès aux ressources financières, cartes de crédit, comptes bancaires, comptes de messagerie, réseaux sociaux, ces systèmes ont toutes ces choses. Si vous vouliez créer une situation de risque maximal, vous doteriez les systèmes d’IA de capacités de planification à long terme et d’un accès direct au monde par tous ces mécanismes. Le danger est, évidemment, que nous créons des systèmes capables de surpasser les êtres humains et nous le faisons sans avoir résolu le problème de contrôle. Le problème de contrôle est : Comment pouvons-nous nous assurer que les systèmes d’IA n’agissent jamais de manière opposée aux intérêts humains ? Nous savons déjà qu’ils le font parce que nous l’avons vu se produire encore et encore avec des systèmes d’IA qui mentent intentionnellement à des êtres humains. Par exemple, lorsque GPT-4 était testé, pour voir s’il pouvait pénétrer dans d’autres systèmes informatiques, il a été confronté à un système informatique doté d’un Captcha. Une sorte de diagramme avec du texte où il est difficile pour les algorithmes de vision par ordinateur de lire le texte. Il a trouvé un être humain sur Task Rabbit et a dit à cette personne qu’il était une personne malvoyante qui avait besoin d’aide pour lire le Captcha, et a donc payé cette personne pour lire le Captcha et ça lui a permis de pénétrer dans le système informatique. Pour moi, quand les entreprises disent : « Nous allons dépenser 400 milliards de dollars au cours des deux prochaines années ou peu importe pour créer une AGI. Nous n’avons pas la moindre idée de ce qui se passe si nous réussissons. » Il me semble essentiel de dire : « Arrêtez. Jusqu’à ce que vous puissiez comprendre ce qui se passe si vous réussissez et comment vous allez contrôler la chose que vous construisez. » Tout comme si quelqu’un disait : « Je veux construire une centrale nucléaire. » « Comment allez-vous faire cela ? » « Je vais rassembler beaucoup d’uranium enrichi et en faire un gros tas. » Vous dites : « Comment allez-vous l’empêcher d’exploser et de tuer tout le monde dans un rayon de 160 kilomètres ? » Vous dites : « Je n’en ai aucune idée. » C’est la situation dans laquelle nous nous trouvons.

Ima: Merci. Les systèmes d’IA à usage général rendent plus facile et moins coûteux pour les individus de mener des cyberattaques, même sans expertise approfondie. Nous disposons de premières indications que l’IA pourrait aider à identifier les vulnérabilités, mais nous n’avons pas encore de preuves solides que l’IA peut entièrement automatiser des tâches complexes de cybersécurité de manière à avantager significativement les attaquants plutôt que les défenseurs. Que s’est-il passé vendredi dernier ? La récente panne informatique mondiale causée par une mise à jour défectueuse du logiciel sert de rappel brutal de la vulnérabilité de notre infrastructure numérique et de la dévastation que peuvent causer les perturbations à grande échelle. Compte tenu de ces développements et préoccupations, pourriez-vous partager vos réflexions sur deux points clés ? A) Quelles nouvelles capacités offensives en matière de cybersécurité pensez-vous que l’IA pourrait permettre dans un avenir proche, et B) compte tenu de notre dépendance à l’infrastructure numérique, à quels types d’impacts devons-nous nous préparer si les cyberattaques améliorées par l’IA deviennent plus fréquentes ? Merci.