Op-ed: On Robot-delivered Bombs

Contents

“In An Apparent First, Police Used A Robot To Kill.” So proclaimed a headline on NPR’s website, referring to the method Dallas police used to end the standoff with Micah Xavier Johnson. Johnson, an army veteran, shot 12 police officers Thursday night, killing five of them. After his attack, he holed himself up in a garage and told police negotiators that he would kill more officers in the final standoff. As Dallas Police Chief David Brown said at a news conference on Friday morning, “[w]e saw no other option but to use our bomb robot and place a device on its extension for it to detonate where the subject was. Other options would have exposed our officers to grave danger.”

The media’s coverage of this incident generally has glossed over the nature of the “robot” that delivered the lethal bomb. The robot was not an autonomous weapon system that operated free of human control. Rather, it was a remote-controlled bomb disposal robot–one that was sent, ironically, to deliver and detonate a bomb rather than to remove or defuse one. Such a robot can be analogized to the unmanned aerial vehicles or “drones” that have seen increasing military and civilian use in recent years–there is a human somewhere who is controlling every significant aspect of the robot’s movements.

Legally, I don’t think the use of such a remote-controlled device to deliver lethal force presents any special challenges. Because a human is always in control of the robot the lines of legal liability are no different than if the robot’s human operator had walked over and placed the bomb himself. I don’t think that entering the command that led to the detonation of the bomb was any different from a legal standpoint than a sniper pulling the trigger on a rifle. The accountability problems that arise with autonomous weapons simply are not present when lethal force is delivered by a remote-controlled device.

But that is not to say that there are no ethical challenges with police delivering lethal force remotely. As with aerial drones, a bomb disposal robot can deliver lethal force without placing the humans making the decision to kill in danger. The absence of risk creates a danger that the technology will be overused.

That issue has already been widely discussed in the context of military drones. Military commanders think carefully before ordering pilots to fly into combat zones to conduct air strikes, because they know it will place those pilots at risk. They presumably have less hesitation about ordering air strikes using drones, which would not place any of the men and women under their command in harm’s way. That absence of physical risk may make the decision to use lethal force easier, as explained in a 2014 report produced by the Stimson Center on US Drone Policy:

The increasing use of lethal UAVs may create a slippery slope leading to continual or wider wars. The seemingly low-risk and low-cost missions enabled by UAV technologies may encourage the United States to fly such missions more often, pursuing targets with UAVs that would be deemed not worth pursuing if manned aircraft or special operation forces had to be put at risk. For similar reasons, however, adversarial states may be quicker to use force against American UAVs than against US manned aircraft or military personnel. UAVs also create an escalation risk insofar as they may lower the bar to enter a conflict, without increasing the likelihood of a satisfactory outcome.

The same concerns apply to the use of robo-bombs by police in civilian settings. The exceptional danger that police faced in the Dallas standoff makes the use of robot-delivered force in that situation fairly reasonable. But the concern is that police will be increasingly tempted to use the technology in less exceptional situations. As Ryan Calo said in the NPR story, “the time to get nervous about police use of robots isn’t in extreme, anomalous situations with few good options like Dallas, but if their use should become routine.” The danger is that the low-risk nature of robot-delivered weapons makes it more likely that their use will become routine.

Of course, there is another side of that coin. Human police officers facing physical danger, or even believing that they are facing such danger, can panic or overreact,. That may lead them to use lethal force in situations where it is not warranted out of a sense of self-preservation. That may well have been what happened in the shooting of Philando Castile, whose tragic and unnecessary death at the hands of police apparently helped drive Micah Xavier Johnson to open fire on Dallas police officers. A police officer controlling a drone or similar device from the safely of a control room will feel no similar compulsion to use lethal force for reasons of self-preservation.

Legally, I think that the bottom line should be this: police departments’ policies on the use of lethal force should be the same regardless of whether that force is delivered personally or remotely. Many departments’ policies and standards have been under increased scrutiny due to the high-profile police shootings of the past few years, but the gist of those policies is still almost always some variation of: “police officers are not allowed to use lethal force unless they reasonably believe that the use of such force is necessary to prevent death or serious injury to the officer or a member of the public.”

I think that standard was met in Dallas. And who knows? Since the decision to use a robot-delivered bomb came about only because of the unique nature of the Dallas standoff, it’s possible that we won’t see another similar use of robots by police for years to come. But if such an incident does happen again, we may look back on the grisly and dramatic end to the Dallas standoff as a turning point.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, Recent News

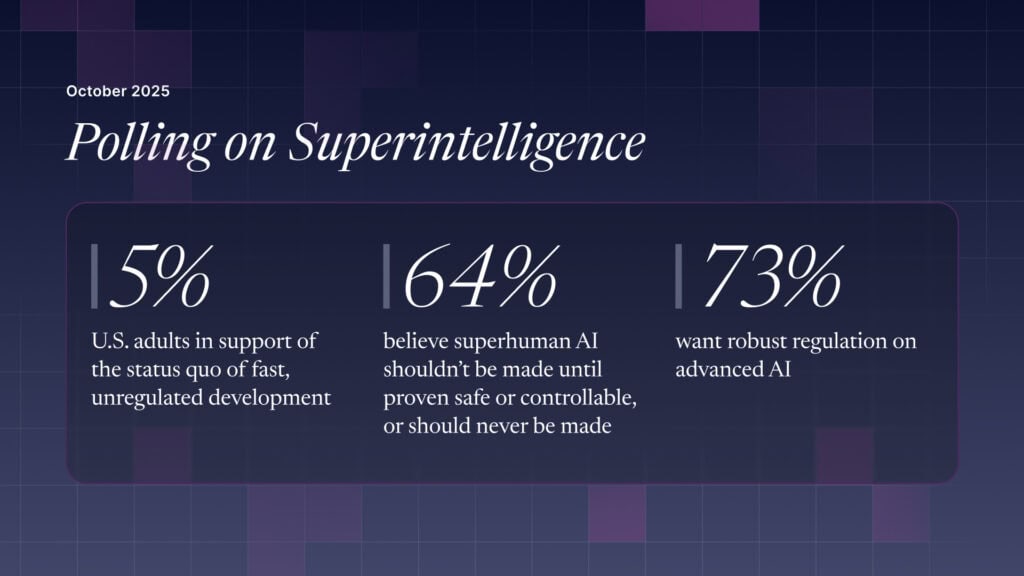

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI