Can We Ensure Privacy in the Era of Big Data?

Contents

Personal Privacy Principle: People should have the right to access, manage and control the data they generate, given AI systems’ power to analyze and utilize that data.

A major change is coming, over unknown timescales but across every segment of society, and the people playing a part in that transition have a huge responsibility and opportunity to shape it for the best. What will trigger this change? Artificial intelligence.

The 23 Asilomar AI Principles offer a framework to help artificial intelligence benefit as many people as possible. But, as AI expert Toby Walsh said of the Principles, “Of course, it’s just a start. … a work in progress.” The Principles represent the beginning of a conversation, and now we need to follow up with broad discussion about each individual principle. You can read the weekly discussions about previous principles here.

Personal Privacy

In the age of social media and online profiles, maintaining privacy is already a tricky problem. As companies collect ever-increasing quantities of data about us, and as AI programs get faster and more sophisticated at analyzing that data, our information can become both a commodity for business and a liability for us.

We’ve already seen small examples of questionable data use, such as Target recognizing a teenager was pregnant before her family knew. But this is merely advanced marketing. What happens when governments or potential employers can gather what seems like innocent and useless information (like grocery shopping preferences) to uncover your most intimate secrets – like health issues even you didn’t know about yet?

It turns out, all of the researchers I spoke to strongly agree with the Personal Privacy Principle.

The Importance of Personal Privacy

“I think that’s a big immediate issue,” says Stefano Ermon, an assistant professor at Stanford. “I think when the general public thinks about AI safety, maybe they think about killer robots or these kind of apocalyptic scenarios, but there are big concrete issues like privacy, fairness, and accountability.”

“I support that principle very strongly!” agrees Dan Weld, a professor at the University of Washington. “I’m really quite worried about the loss of privacy. The number of sensors is increasing and combined with advanced machine learning, there are few limits to what companies and governments can learn about us. Now is the time to insist on the ability to control our own data.”

Toby Walsh, a guest professor at the Technical University of Berlin, also worries about privacy. “Yes, this is a great one, and actually I’m really surprised how little discussion we have around AI and privacy,” says Walsh. “I thought there was going to be much more fallout from Snowden and some of the revelations that happened, and AI, of course, is enabling technology. If you’re collecting all of this data, the only way to make sense of it is to use AI, so I’ve been surprised that there hasn’t been more discussion and more concern amongst the public around these sorts of issues.”

Kay Firth-Butterfield, an adjunct professor at the University of Texas in Austin, adds, “As AI becomes more powerful, we need to take steps to ensure that it cannot use our personal data against us if it falls into the wrong hands.”

Taking this concern a step further, Roman Yampolskiy, an associate professor at the University of Louisville, argues that “the world’s dictatorships are looking forward to opportunities to target their citizenry with extreme levels of precision.”

“The tech we will develop,” he continues, “will most certainly become available throughout the world and so we have a responsibility to make privacy a fundamental cornerstone of any data analysis.”

But some of the researchers also worry about the money to be made from personal data.

Ermon explains, “Privacy is definitely a big one, and one of the most valuable things that these large corporations have is the data they are collecting from us, so we should think about that carefully.”

“Data is worth money,” agrees Firth-Butterfield, “and as individuals we should be able to choose when and how to monetize our own data whilst being encouraged to share data for public health and other benefits.”

Francesca Rossi, a research scientist for IBM, believes this principle is “very important,” but she also emphasizes the benefits we can gain if we can share our data without fearing it will be misused. She says, “People should really have the right to own their privacy, and companies like IBM or any other that provide AI capabilities and systems should protect the data of their clients. The quality and amount of data is essential for many AI systems to work well, especially in machine learning. … It’s also very important that these companies don’t just assure that they are taking care of the data, but that they are transparent about the use of the data. Without this transparency and trust, people will resist giving their data, which would be detrimental to the AI capabilities and the help AI can offer in solving their health problems, or whatever the AI is designed to solve.”

Privacy as a Social Right

Both Yoshua Bengio and Guruduth Banavar argued that personal privacy isn’t just something that AI researchers should value, but that it should also be considered a social right.

Bengio, a professor at the University of Montreal, says, “We should be careful that the complexity of AI systems doesn’t become a tool for abusing minorities or individuals who don’t have access to understand how it works. I think this is a serious social rights issue.” But he also worries that preventing rights violations may not be an easy technical fix. “We have to be careful with that because we may end up barring machine learning from publicly used systems, if we’re not careful,” he explains, adding, “the solution may not be as simple as saying ‘it has to be explainable,’ because it won’t be.”

And as Ermon says, “The more we delegate decisions to AI systems, the more we’re going to run into these issues.”

Meanwhile, Banavar, the Vice President of IBM Research, considers the issue of personal privacy rights especially important. He argues, “It’s absolutely crucial that individuals should have the right to manage access to the data they generate. … AI does open new insight to individuals and institutions. It creates a persona for the individual or institution – personality traits, emotional make-up, lots of the things we learn when we meet each other. AI will do that too and it’s very personal. I want to control how persona is created. A persona is a fundamental right.”

What Do You Think?

And now we turn the conversation over to you. What does personal privacy mean to you? How important is it to have control over your data? The experts above may have agreed about how serious the problem of personal privacy is, but solutions are harder come by. Do we need to enact new laws to protect the public? Do we need new corporate policies? How can we ensure that companies and governments aren’t using our data for nefarious purposes – or even for well-intentioned purposes that still aren’t what we want? What else should we, as a society, be asking?

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, AI Safety Principles, Recent News

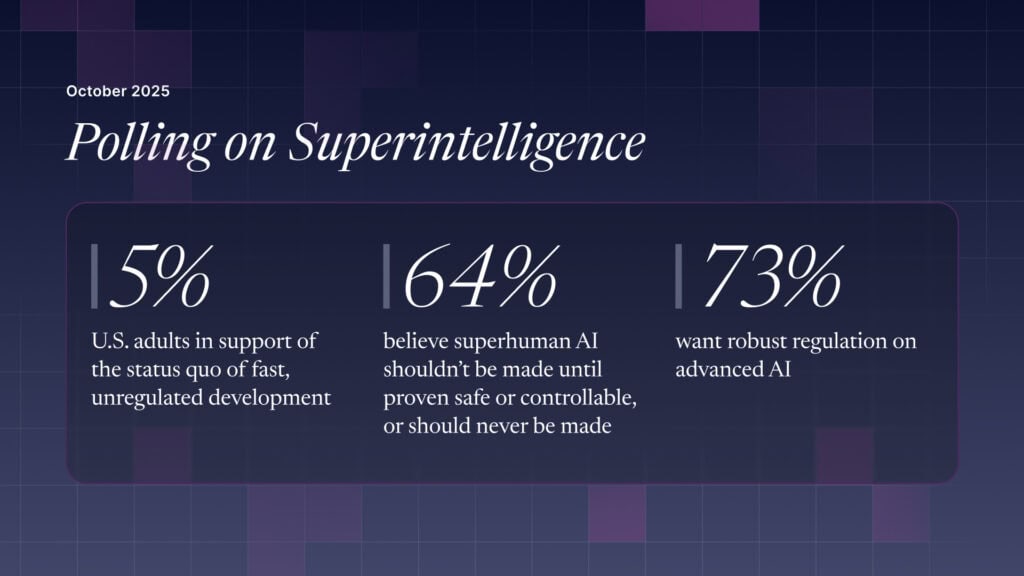

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI