Why You Should Care About AI Agents

Contents

The AI field is abuzz with talk of ‘agents’, the next iteration of AI poised to cause a step-change in the way we interact with the digital world (and vice versa!). Since the release of ChatGPT in 2022, the dominant AI paradigm has been Large Language Models (LLMs), text-based question and answer systems that, while their capabilities continue to become more impressive, can only respond passively to queries they are given.

Now, companies have their sights set on models that can proactively suggest and implement plans, and take real-world actions on behalf of their users. This week, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman predicted that we will soon be able to “give an AI system a pretty complicated task, the kind of task you’d give to a very smart human”, and that if this works as intended, it will “really transform things”. The company’s Chief Product Officer Kevin Weil also hinted at behind-the-scenes developments, claiming: “2025 is going to be the year that agentic systems finally hit the mainstream”. AI commentator Jeremy Kahn has forecasted a flurry of AI agent releases over the next six to eight months from tech giants including Google, OpenAI and Amazon. In just the last two weeks, Microsoft significantly increased the availability of purpose-built and custom autonomous agents within Copilot Studio, in an expansion of what Venturebeat is calling the industry’s “largest AI agent ecosystem”.

So what exactly are AI agents, and how soon (if ever) can we expect them to become ubiquitous? Should their emergence excite us, worry us, or both? We’ve investigated the state-of-the-art in AI agents and where it might be going next.

What is an AI agent?

Defining what exactly constitutes an ‘AI agent’ is a surprisingly thorny task. We could simply call any model that can perform actions on behalf of users an agent, though even LLMs such as ChatGPT might reasonably fall under this umbrella – they can construct entire essays based off of vague prompts by making a series of independent decisions about form and content, for example. But this definition fails to get at the important differences between today’s chat-based systems, and the agents that tech giants have hinted may be around the corner.

Agency exists on a spectrum. The more agency a system has, the more complex tasks it can handle end-to-end without human intervention. When people talk about the next generation of agents, they are usually referring to systems that can perform entire projects without continuous prompting from a human.

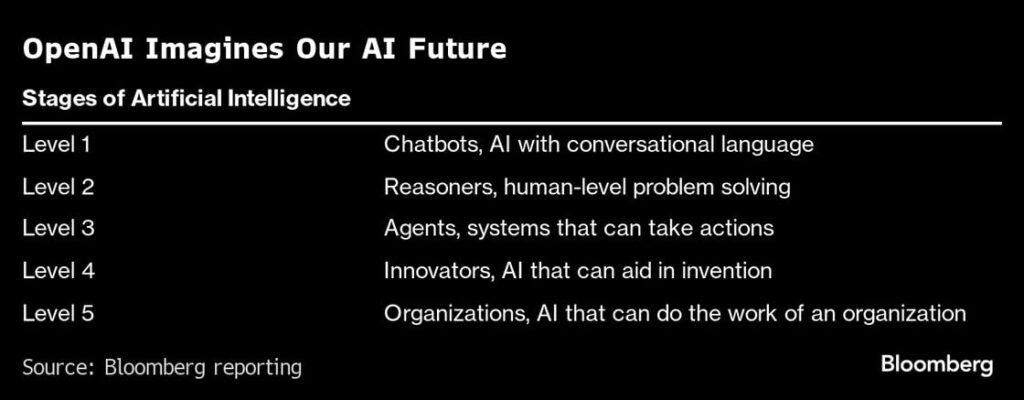

This general trend towards more agentic systems is one of the most important axes of AI development. OpenAI places ‘agents’ at the third rung on a five-step ladder towards Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). They define agents as systems that can complete multi-day tasks on behalf of users. Insiders have disclosed that the company believes itself to be closing in on the second of these five stages already, meaning that systems this transformative be just around the corner.

The difference between the chatbots of today and the agents of tomorrow becomes clearer when we consider a concrete example. Take planning a holiday: A system like GPT-4 can suggest an itinerary if you manually provide your dates, budget, and preferences. But a sufficiently powerful AI agent would transform this process. Its key advantage would be the ability to interact with external systems – it could select ideal dates by accessing your calendar, understand your preferences through your search history, social media presence and other digital footprints, and use your payment and contact details to book flights, hotels and restaurants. One text prompt to your AI assistant could set in motion an automated chain of events that culminates in a meticulous itinerary and several booking confirmations landing in your inbox.

In this video demo, an AI agent is prompted by a single prompt to send an email invitation and purchase a gift:

The holiday-booking and gift-buying scenarios are two intuitive (and potentially imminent) examples, though they are dwarfed in significance if we consider the actions that AI agents might be able to autonomously achieve as their capabilities grow. Advanced agents might be able to execute on prompts that go far beyond “plan a holiday”, able to deliver results for prompts like “design, market and launch an app” or “turn this $100,000 into $1 million” (this is a milestone that AI luminary and DeepMind co-founder Mustafa Suleyman has publicly predicted AIs will reach by 2025). In theory, there is no ceiling to how complex a task AI systems might be able to independently complete as their capabilities and integration with the wider world increase.

We’ve been focusing so far on software agents that are emerging at the frontier of general-purpose AI development, but these are of course not the only type of AI agent out there! There are many agents that already interact with the real world, such as self-driving cars and delivery drones. They use sensors to perceive their environment, complete complex, multi-step tasks without human intervention, and can react to unexpected changes in their environment. Though these agents are highly capable, they are only trained to perform a narrow set of actions (your Waymo isn’t going to start pontificating on moral philosophy in the middle of your morning commute). AI agents that have the ability to generalise across domains, and build on the capabilities of today’s state-of-the-art LLMs, are what will likely be the most transformative – which is why we’re primarily focusing on them here.

The AI agent state-of-the-art

Tech leaders have bold visions for a future that humans share with powerful AI agents. Sam Altman imagines each of us having access to “a super-competent colleague that knows absolutely everything” about our lives. DeepMind CEO Demmis Hassabis envisions “a universal assistant” that is “multimodal” and “with you all the time”. How close are they to realising these ambitions?

Here’s how much progress each of the leading AI companies has made towards advanced agents.

OpenAI

OpenAI has yet to release any products explicitly marketed as ‘agents’, though several of its products have already demonstrated some capacity for automation of complex tasks. For example, its Advanced Data Analytics tool (which is built into ChatGPT and was previously known as Code Inpreter), can write and run Python code on a user’s behalf, and independently complete tasks such as data scrubbing.

Custom GPTs are another OpenAI product that represent an important step on the way to fully autonomous agents. They can already be connected to external services and databases, which means you can create AI assistants to, for example, read and send emails, or help you with online shopping.

According to several reports, OpenAI plans to release an agent named Operator as soon as January 2025, which will have capabilities such as autonomous web browsing, making purchases, and completing routine tasks like scheduling meetings.

Anthropic

Anthropic recently released a demo of its new computer use feature, which allows its model, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to operate computers on a user’s behalf. The model uses multimodal capabilities to ‘see’ what is happening on a screen, and count the number of pixels the cursor needs to be moved vertically or horizontally in order to click in the correct place.

The feature is still fairly error-prone, but Claude currently scores higher than any other model on OSWorld, a benchmark designed to evaluate how well AI models can complete multi-step computer tasks – making it state-of-the-art in what will likely be one of the most important capabilities for advanced agents.

Google Deepmind

Deepmind has been experimenting with AI agents in the videogame sphere, where they have created a Scalable Instructable Multiworld Agent (SIMA). SIMA can carry out complex tasks in virtual environments by following natural language prompts. Similar techniques could help produce agents that can act in the real world.

Project Astra is DeepMind’s ultimate vision for an universal, personalised AI agent. Currently in its prototype phase, the agent is pitched as set apart by its multimodal capabilities. CEO Demis Hassabis imagines that Astra will ultimately become an assistant that can ‘live’ on multiple devices and will carry about complex tasks on a user’s behalf.

Why are people building AI agents?

The obvious answer to this question is that reliable AI agents are just very useful, and will become more so as their power increases. At the personal level, a personal assistant of the type that DeepMind is attempting to build could liberate us from much of the mundane admin associated with everyday life (booking appointments, scheduling meetings, paying bills…) and free us up to spend time on the many things we’d rather be doing. On the company side, they have the clear potential to boost productivity and cut costs – for example, publishing company Wiley saw a 40% efficiency increase after adopting a much-publicised agent platform offered by Salesforce.

If developers can ensure that AI agents do not fall prey to technical failures such as hallucinations, it’s possible that they could prove more reliable than humans in high-stakes environments. OpenAI’s GPT-4 already outcompetes human doctors at diagnosing illnesses. Similarly accurate AI agents that can think over long enough time horizons to design treatment plans and assist in providing sustained care to patients, for example, could save lives if deployed at scale. Studies have also suggested that autonomous vehicles cause accidents at a lower rate than human drivers, meaning that widespread adoption of self-driving cars would lead to fewer traffic accidents.

Are we ready?

A world populated with extremely competent AI agents that interact autonomously with the digital and physical worlds may not be far away. Taking this scenario seriously raises many ethical dilemmas, and forces us to consider a wide spectrum of possible risks. Safety teams at leading AI labs are racing to answer these questions as the AI-agent era draws nearer, though the path forward remains unclear.

Malfunctions and technical failures

One obvious way in which AI agents could pose risks is in the same, mundane way that so many technologies before them have – we could deploy them in a high stakes environment, and they could break.

Unsurprisingly, there have been cases of AI agents malfunctioning in ways that caused harm. In one high-profile case, for example, a self-driving car in San Francisco struck a pedestrian, and failing to register that she was still pinned under its wheels, dragged her 20 feet as it attempted to pull over. The point isn’t necessarily that AI agents are (or will be) more unreliable than humans – as mentioned above, the opposite may even be true in the case of self-driving cars. But these early, small-scale failures are harbingers of larger ones that will inevitably occur as we deploy agentic systems at scale. Imagine the havoc that a malfunctioning agent could cause if it had been appointed CEO of a company (this may sound far-fetched, but has already happened)!

Misalignment risks

If in the early days of agentic AI systems, we have to worry about AIs not reasoning well enough, increasing capabilities may lead to the opposite problem – agents that reason too well, and that we have failed to sufficiently align with our interests. This opens up a suite of risks in a category that AI experts refer to as ‘misalignment’. In simple terms, a misaligned AI is one that is pursuing different objectives to those of its creators (or pursuing the right objectives, but using unexpected methods). There are good reasons to expect that the default behaviour of extremely capable but misaligned agents may be dangerous. For example, they could be incentivised to seek power or resist shutdown in order to achieve their goals.

There have already been examples of systems that pretend to act in the interests of users while harbouring ulterior motives (deception), tell users what they want to hear even if it isn’t true (sycophancy) or cut corners to elicit human approval (reward-hacking). These systems were unable to cause widespread harm, due to remaining less capable than humans. But if we do not find robust, scalable ways to ensure AIs always behave as intended, powerful agents may be both motivated and able to execute complex plans that harm us. This is why many experts are worried that advanced AI may pose catastrophic or even existential risks to humanity.

Opaque reasoning

We know that language models like ChatGPT work very well, but we have surprisingly little idea how they work. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei recently estimated that we currently understand just 3% what happens inside artificial neural networks. There is an entire research agenda called mechanistic interpretability, which seeks to learn more about how AI systems acquire knowledge and make decisions – though it may be challenging for progress to keep pace with improvement in AI’s capabilities. The more complex plans AI agents are able to execute, the more of a problem this might pose. Their decision making processes may eventually prove too complicated for us to interpret, and we may have no way to verify whether they are being truthful about their intentions.

This exacerbates the problem of misalignment described above. For example, if an AI agent formulates a complex plan that involves deceiving humans, and we are unable to ‘look inside’ its neural network and decode its reasoning, we are unlikely to realise we are being deceived in time to intervene.

Malicious use

The problem of reliably getting powerful AI agents to do as we say is mirrored by another – what about situations where we don’t want them to follow their user’s instructions? Experts have long been concerned about the misuse of powerful AI, and the rationale behind this fear is very simple: there likely are many more actors in the world who want to do widespread harm than have the ability to. This is a gap that AI could help to close.

For example, consider a terrorist group attempting to build a bioweapon. Currently, highly-specialised, PhD-level knowledge is required to do this successfully – and current LLMs have, so far, not meaningfully lowered this bar to entry. But imagine that this terrorist group had access to a highly capable AI agent of the type that may exist in the not-too-distant future. A purely ‘helpful’ agent would faithfully assist them in acquiring the necessary materials, conducting research, running simulations, developing the pathogen, and carrying out an attack. Depending on how agentic this system is, it could do anything from providing support at each separate stage of this process to formulating and executing the entire plan autonomously.

AI companies apply safety features to their models to prevent them from producing harmful outputs. However, there are many examples of models being jailbroken using clever prompts. More and more powerful models are also being open-sourced, which makes safety features easy and cheap to remove. It therefore seems likely that malicious actors will find ways to use powerful AI agents to cause harm in the future.

Job automation

Even if we manage to prevent AI agents from malfunctioning or being misused in ways that prove catastrophically harmful, we’ll still be left to grapple with the issue of job automation. Though this is a perennial problem of technological progress, there are good reasons to think that this time really is different – after all, the stated goal of frontier companies is to create AI systems that “outperform humans at most economically valuable work”.

It’s easy to imagine how general-purpose AI agents might cause mass job displacement. They will be deployable in any context, able to work 24/7 without breaks or pay, and capable of producing work much more quickly than their human equivalents. If we really do get AI agents that are this competent and reliable, companies will have a strong economic incentive to replace human employees in order to remain competitive.

The transition to a world of AI agents

AI agents are coming – and soon. There may not be a discrete point at which we move from a ‘tool AI’ paradigm to a world teaming with AI agents. Instead, this transition is likely to happen subtly as AI companies release models that are able to handle incrementally more complex tasks.

AI agents hold tremendous promise. They could automate mundane tasks and free us up to pursue more creative projects. They could help us make important scientific breakthroughs in spheres such as sustainable energy and medicine. But managing this transition carefully requires addressing a number of critical issues, such as how to reliably control advanced agents, and what social safety nets we should have in place in a largely automated economy.

About the author

Sarah Hastings-Woodhouse is an independent writer and researcher with an interest in educating the public about risks from powerful AI and other emerging technologies. Previously, she spent three years as a full-time Content Writer creating resources for prospective postgraduate students. She holds a Bachelors degree in English Literature from the University of Exeter.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI

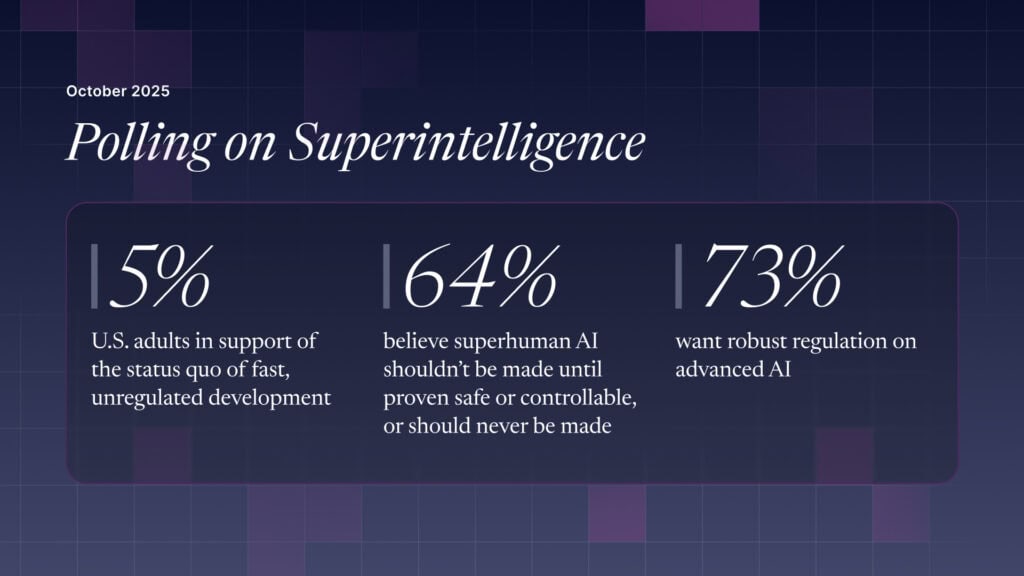

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI