FHI: Putting Odds on Humanity’s Extinction

Contents

Not long ago, I drove off in my car to visit a friend in a rustic village in the English countryside. I didn’t exactly know where to go, but I figured it didn’t matter because I had my navigator at the ready. Unfortunately for me, as I got closer, the GPS signal became increasingly weak and eventually disappeared. I drove around aimlessly for a while without a paper map, cursing my dependence on modern technology.

It may seem gloomy to be faced with a graph that predicts the potential for extinction, but the FHI researchers believe it can stimulate people to start thinking—and take action.

But as technology advances over the coming years, the consequences of it failing could be far more troubling than getting lost. Those concerns keep the researchers at the Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) in Oxford occupied—and the stakes are high. In fact, visitors glancing at the white boards surrounding the FHI meeting area would be confronted by a graph estimating the likelihood that humanity dies out within the next 100 years. Members of the Institute have marked their personal predictions, from some optimistic to some seriously pessimistic views estimating as high as a 40% chance of extinction. It’s not just the FHI members: at a conference held in Oxford some years back, a group of risk researchers from across the globe suggested the likelihood of such an event is 19%. “This is obviously disturbing, but it still means that there would be 81% chance of it not happening,” says Professor Nick Bostrom, the Institute’s director.

That hope—and challenge—drove Bostrom to establish the FHI in 2005. The Institute is devoted precisely to considering the unintended risks our technological progress could pose to our existence. The scenarios are complex and require forays into a range of subjects including physics, biology, engineering, and philosophy. “Trying to put all of that together with a detailed attempt to understand the capabilities of what a more mature technology would unleash—and performing ethical analysis on that—seemed like a very useful thing to do,” says Bostrom.

Far from being bystanders in the face of apocalypse, the FHI researchers are working hard to find solutions.

In that view, Bostrom found an ally in British-born technology consultant and author James Martin. In 2004, Martin had donated approximately $90 million US dollars—one of the biggest single donations ever made to the University of Oxford—to set up the Oxford Martin School. The school’s founding aim was to address the biggest questions of the 21st Century, and Bostrom’s vision certainly qualified. The FHI became part of the Oxford Martin School.

Before the FHI came into existence, not much had been done on an organised scale to consider where our rapid technological progress might lead us. Bostrom and his team had to cover a lot of ground. “Sometimes when you are in a field where there is as yet no scientific discipline, you are in a pre-paradigm phase: trying to work out what the right questions are and how you can break down big, confused problems into smaller sub-problems that you can then do actual research on,” says Bostrom.

Though the challenge might seem like a daunting task, researchers at the Institute have a host of strategies to choose from. “We have mathematicians, philosophers, and scientists working closely together,” says Bostrom. “Whereas a lot of scientists have kind of only one methodology they use, we find ourselves often forced to grasp around in the toolbox to see if there is some particular tool that is useful for the particular question we are interested in,” he adds. The diverse demands on their team enable the researchers to move beyond “armchair philosophising”—which they admit is still part of the process—and also incorporate mathematical modelling, statistics, history, and even engineering into their work.

“We can’t just muddle through and learn from experience and adapt. We have to anticipate and avoid existential risk. We only have one chance.”

– Nick Bostrom

Their multidisciplinary approach turns out to be incredibly powerful in the quest to identify the biggest threats to human civilisation. As Dr. Anders Sandberg, a computational neuroscientist and one of the senior researchers at the FHI explains: “If you are, for instance, trying to understand what the economic effects of machine intelligence might be, you can analyse this using standard economics, philosophical arguments, and historical arguments. When they all point roughly in the same direction, we have reason to think that that is robust enough.”

The end of humanity?

Using these multidisciplinary methods, FHI researchers are finding that the biggest threats to humanity do not, as many might expect, come from disasters such as super volcanoes, devastating meteor collisions or even climate change. It’s much more likely that the end of humanity will follow as an unintended consequence of our pursuit of ever more advanced technologies. The more powerful technology gets, the more devastating it becomes if we lose control of it, especially if the technology can be weaponized. One specific area Bostrom says deserves more attention is that of artificial intelligence. We don’t know what will happen as we develop machine intelligence that rivals—and eventually surpasses—our own, but the impact will almost certainly be enormous. “You can think about how the rise of our species has impacted other species that existed before—like the Neanderthals—and you realise that intelligence is a very powerful thing,” cautions Bostrom. “Creating something that is more powerful than the human species just seems like the kind of thing to be careful about.”

Nick Bostrom, Future of Humanity Institute Director

Far from being bystanders in the face of apocalypse, the FHI researchers are working hard to find solutions. “With machine intelligence, for instance, we can do some of the foundational work now in order to reduce the amount of work that remains to be done after the particular architecture for the first AI comes into view,” says Bostrom. He adds that we can indirectly improve our chances by creating collective wisdom and global access to information to allow societies to more rapidly identify potentially harmful new technological advances. And we can do more: “There might be ways to enhance biological cognition with genetic engineering that could make it such that if AI is invented by the end of this century, might be a different, more competent brand of humanity ,” speculates Bostrom.

Perhaps one of the most important goals of risk researchers for the moment is to raise awareness and stop humanity from walking headlong into potentially devastating situations. And they are succeeding. Policy makers and governments around the globe are finally starting to listen and actively seek advice from researchers like those at the FHI. In 2014 for instance, FHI researchers Toby Ord and Nick Beckstead wrote a chapter for the Chief Scientific Adviser’s annual report setting out how the government in the United Kingdom should evaluate and deal with existential risks posed by future technology. But the FHI’s reach is not limited to the United Kingdom. Sandberg was on the advisory board of the World Economic Forum to give guidance on the misuse of emerging technologies for the report that concludes a decade of global risk research published this year.

Despite the obvious importance of their work the team are still largely dependent on private donations. Their multidisciplinary and necessarily speculative work does not easily fall into the traditional categories of priority funding areas drawn up by mainstream funding bodies. In presentations, Bostrom has been known to show a graph that depicts academic interest for various topics, from dung beetles and Star Trek to zinc oxalate, which all appear to receive far greater credit than the FHI’s type of research concerning the continued existence of humanity. Bostrom laments this discrepancy between stakes and attention: “We can’t just muddle through and learn from experience and adapt. We have to anticipate and avoid existential risk. We only have one chance.”

“Creating something that is more powerful than the human species just seems like the kind of thing to be careful about.”

It may seem gloomy to be faced every day with a graph that predicts the potential disasters that could befall us over the coming century, but instead, the researchers at the FHI believe that such a simple visual aid can stimulate people to face up to the potentially negative consequences of technological advances.

Despite being concerned about potential pitfalls, the FHI researchers are quick to agree that technological progress has made our lives measurably better over the centuries, and neither Bostrom nor any of the other researchers suggest we should try to stop it. “We are getting a lot of good things here, and I don’t think I would be very happy living in the Middle Ages,” says Sandberg, who maintains an unflappable air of optimism. He’s confident that we can foresee and avoid catastrophe. “We’ve solved an awful lot of other hard problems in the past,” he says.

Technology is already embedded throughout our daily existence and its role will only increase in the coming years. But by helping us all face up to what this might mean, the FHI hopes to allow us not to be intimidated and instead take informed advantage of whatever advances come our way. How does Bostrom see the potential impact of their research? “If it becomes possible for humanity to be more reflective about where we are going and clear-sighted where there may be pitfalls,” he says, “then that could be the most cost-effective thing that has ever been done.”

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, Biotech, Climate & Environment, Nuclear, Partner Orgs

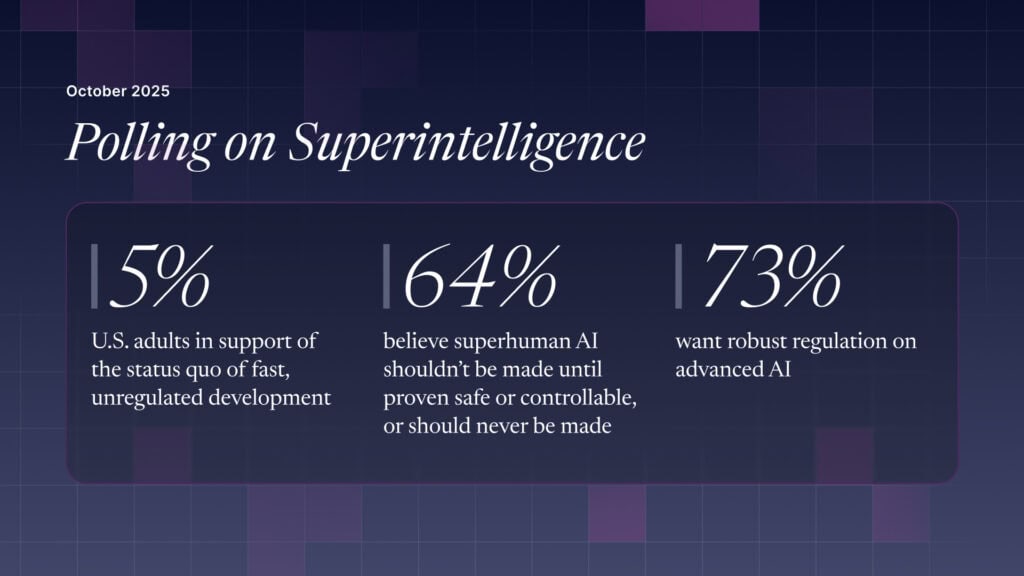

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI