Future of Life Award 2020: Saving 200,000,000 Lives by Eradicating Smallpox

- William Foege's and Victor Zhdanov's efforts to eradicate smallpox

- Personal stories from Foege's and Zhdanov's lives

- The history of smallpox

- Biological issues of the 21st century

18:51 Implementing surveillance and containment throughout the world after success in West Africa

23:55 Wrapping up with eradication and dealing with the remnants of smallpox

25:35 Lab escape of smallpox in Birmingham England and the final natural case

27:20 Part 2: Introducing Michael Burkinsky as well as Victor and Katia Zhdanov

29:45 Introducing Victor Zhdanov Sr. and Alissa Zhdanov

31:05 Michael Burkinsky's memories of Victor Zhdanov Sr.

39:26 Victor Zhdanov Jr.'s memories of Victor Zhdanov Sr.

46:15 Mushrooms with meat

47:56 Stealing the family car

49:27 Victor Zhdanov Sr.'s efforts at the WHO for smallpox eradication

58:27 Exploring Alissa's book on Victor Zhdanov Sr.'s life

1:06:09 Michael's view that Victor Zhdanov Sr. is unsung, especially in Russia

1:07:18 Part 3: William Foege on the history of smallpox and biology in the 21st century

1:07:32 The origin and history of smallpox

1:10:34 The origin and history of variolation and the vaccine

1:20:15 West African "healers" who would create smallpox outbreaks

1:22:25 The safety of the smallpox vaccine vs. modern vaccines

1:29:40 A favorite story of William Foege's

1:35:50 Larry Brilliant and people central to the eradication efforts

1:37:33 Foege's perspective on modern pandemics and human bias

1:47:56 What should we do after COVID-19 ends

1:49:30 Bio-terrorism, existential risk, and synthetic pandemics

1:53:20 Foege's final thoughts on the importance of global health experts in politics

Transcript

Lucas Perry: Welcome to the Future of Life Institute Podcast. I'm Lucas Perry. Today's episode is with the recipients of the 2020 Future of Life Award. The Future of Life Award is an annual prize we give out to an individual who, without receiving much recognition at the time, has helped make today dramatically better than it may have been otherwise. The 2017 and 2018 winners of the Future of Life Award were Vasili Arkhipov and Stanislav Petrov. Two heroes of the nuclear age that helped prevent accidental nuclear war.

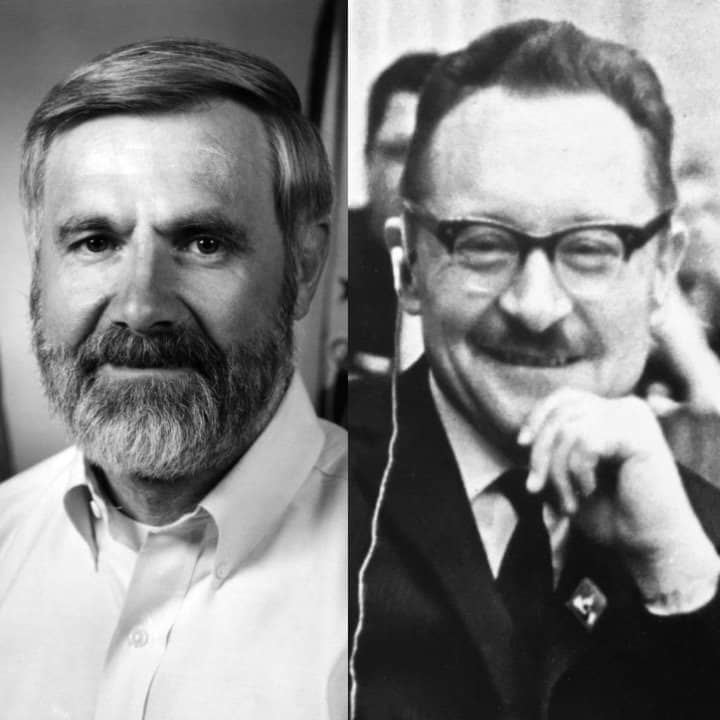

The 2019 winner was Dr. Matthew Meselson for his crucial efforts behind the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, an international ban that has prevented one of the most inhumane forms of warfare known to humanity. This year, we are awarding Viktor Zhdanov and William Foege for their crucial efforts in the eradication of smallpox. Viktor Zhdanov passed away in July of 1987, so his stepson Michael Burkinsky and son, Victor, will be receiving the prize in his honor. William Foege, Michael Burkinsky, Victor Zhdanov Jr., and his wife, Katia, have all joined us today to discuss the award.

For a little background on the 2020 award, smallpox has been around for at least 3000 years and claimed the lives of about 300 million people in the 20th century alone. UNICEF estimates that smallpox eradication has saved close to 200 million lives so far. While serving as the Soviet Union's deputy minister of health, Dr. Viktor Zhdanov, persuasively argued at the 11th World Health Assembly meeting in 1958, that the world could eradicate smallpox within a decade with a united effort, and successfully lobbied the Soviet Union to donate 25 million doses of the smallpox vaccine to kickstart the effort in developing countries.

The World Health Assembly accepted his proposal in 1959 under resolution WHA 11.54. While working for the Centers for Disease Control in Africa as chief of the Smallpox Eradication Program, Dr. William Foege developed the highly successful surveillance and ring vaccination strategy to contain smallpox spread. This greatly reduced the number of vaccinations needed, ensuring that the limited resources available sufficed to make smallpox the first infectious disease to be eradicated in human history. This podcast is broken into three parts.

The first is with William Foege on his experience in the efforts to eradicate smallpox. We then introduce Michael Burkinsky, Victor Zhdanov Jr., and his wife, Katia Zhdanov, where we discuss Viktor Zhdanov Sr. and their memories and accounts of his life. We end by pivoting back to William Foege where he offers us a history of the smallpox virus, as well as his perspective on biological issues in the 21st century. Without further ado, I'm happy to introduce this conversation with the 2020 Future of Life Award recipients.

Thanks again for coming on. I'm excited to take a tour with you through your life's history and the history of smallpox, and also get into a bit of more contemporary problems for the 21st century that are relevant to the Future of Life. Let's start off with your personal life and then we'll get into smallpox more specifically. Could you give a little bit of background about your life's history and life occupation? What it is that has really driven you and captured your heart and mind and attention throughout your life?

William Foege: Okay. I spent my first 10 years in rural Iowa, and then we moved to the Northeast section of the state of Washington. When I was 15, I ended up in a body cast in a town that had no television and therefore reading was the only thing that I could really concentrate on, but I did a lot of reading. At that time, one of the books that caught my attention was by Albert Schweitzer. Albert Schweitzer, a little over a hundred years ago, went to Africa where he spent the rest of his life running a medical center. What was unusual about him is he is what we would now call a polymath.

That is, he was interested in so many things. By the time he was 30, he already had three earned PhD degrees. I mean, that's just incredible. At the same time, he was an accomplished organist, so good that he would give concerts around Europe. He was probably the world's expert on Bach at that time. In addition, he was the world's expert on organ building. He was just interested in so many things. At the age of 30, he decided, "Up until this time I've spent my life doing what I wanted to do. Now I'm going to spend the rest of my life doing something for others."

At the age of 30, he entered medical school, got his fourth doctoral degree, then went to Africa and that's what he did. He spent the rest of his life in what is now Gabon. I was so taken by his story that I became interested in both Africa and in medicine. By the time I was out of high school, I was already getting literature from the World Health Organization and from CDC in Atlanta. Now, CDC was quite new at that time, I don't even recall how I got on their mailing list, but I did. When I started medical school, I found that there were very few people interested in global health.

At the University of Washington in Seattle, I could only find a couple of people that even had an interest. One of them was a very interesting person by the name of Rei Ravenholt. He just died last month at the age of 95. What he said to me is, "If you're actually interested in global health, there is no good pathway." It's not like you want to become a pediatrician and there are residencies that you enroll in it. He said global health, you have to make your own way. He told me at that time, "If you're truly interested, go to Atlanta, join the Epidemic Intelligence Service at CDC.

You'll find other people interested in global health and they will end up as colleagues for the rest of your life." That's what I did. I ended up going to CDC. While there I was stationed in Denver, Colorado working for the entire state, but I got a call one afternoon asking me to investigate what was a suspected case of smallpox in a Navajo child. They told me the book I should get from the library, which was a book by an author by the name of Dixon. I went to the library, found it was checked out by a medical student who was writing a paper.

It took me some time to find that medical student, and of course he didn't want to give up the book, but I finally talked him out of the book. By the time I got to Farmington, New Mexico that night, I had a pretty good idea on how to differentiate smallpox and chickenpox. I entered the hospital that night and as I walked in the patient's door, a little child, less than a year old, I knew looking across the room that I had no idea what that child had. That humbles you very fast because here I was, the out-of-town expert coming in to diagnose smallpox.

I did an examination. I called my bosses back in Atlanta, we discussed what I was finding. They could not make a diagnosis, and so we had to treat it as suspected smallpox. For the next three days, that's what we did. We found all the people who had been in contact with either the patient or their parents. That was my first interest in smallpox. A year later, I went to India because a Peace Corps physician had become ill. I went for three months to replace the physician while they recruited. That's when I saw my first cases of smallpox.

I had read about it, but I had not anticipated what an ugly disease it actually was. The people with smallpox were so disfigured in the hospital that even the staff did not want to deal with them. I came to realize that that was their introduction to, "Even if I survive, people will probably not want to deal with me in the future." About a third of the people died, about a third ended up scarred for life. These poor people had trouble finding marriage partners and they had trouble finding jobs and so forth.

It was then in 1965 that I was at the Harvard School of Public Health, getting a degree in tropical medicine that I did my first paper on smallpox. It was a seminar for a man by the name of Tom Weller, who was a Nobel Laureate for having been one of three people to perfect the growing of polio virus in the lab. This allowed Jonas Salk then to make his vaccine, which came out in 1955. I presented a paper at his seminar class and he was so questioning of everything I said that it made me nervous.

Afterwards, a member of his staff said, "Tom Weller never embarrasses a student. What you saw was true interest. He was so interested in what you were saying, he had to keep asking questions." Well, I went off to Africa, not intending to do anything in smallpox, but I had agreed with a church group to run a medical center. While I was there, CDC sent me a letter asking if I would be a consultant for a new program that they were starting in West Africa. That's how I got into smallpox.

Even before that program started, I was called to an outbreak only to find we didn't have enough vaccine because it was not due to arrive until the next month. We had to figure out how to use the vaccine most efficiently. What we did was to call the missionaries in the area by radio. I found out that they had a network. They would get on the radio every night at seven o'clock just to make sure no one was in dire need of something. I got on the radio, we divided the area up and asked each missionary to send runners to the villages the next day.

24 hours later, we got back on the radio and now we knew exactly which villages had smallpox. We were able to use our limited vaccine in those villages and the remaining vaccine in marketplaces where we thought it might spread next. With less than 7% of the population vaccinated in that area, the outbreaks shopped. It totally surprised us because up until this point, everyone said you had to get 80% coverage in order to get what's called herd immunity. This led us down a road of asking, is there a more efficient way to get rid of smallpox?

We started what we called surveillance-containment. We spent our attention not on vaccinating everybody, but on trying to find where the virus was. The virus leaves a trail because you either find sick people or you find people with pockmarks. You can find out by questioning them how long ago they got those pockmarks. You can actually trail smallpox and know where it's been. What we found was that using that approach, we were able to get rid of smallpox in all of Eastern Nigeria, which is where I was working at the time, in six months' time. It happened so fast.

Then we started to the same approach in the rest of West and Central Africa. In this area of 20 countries, which was now the project of CDC funded by USAID with a five-year goal of getting rid of smallpox, we were able to do it in three years and six months and under budget. That's the way the smallpox story changed. Then we went on to India, which was an even bigger problem. In India, we went from high number of cases, in fact, in May of 1974, one state alone, Bihar, was having 1,500 new cases of smallpox every day, which meant 1500 new investigations every day.

It required a large army of people being hired and trained in order to do that. Once we got the system going in India, they went from these high rates to zero in the entire country in 12 months' time. I think it was probably the most exciting 12 months in all of global health up to that point.

Lucas Perry: What year is it that you're graduating medical school and being told that global health isn't really a ... there's not really a clear pathway to work in that? It's not really established as a field or an endeavor yet.

William Foege: This was in the late 1950s and I graduated from medical school in 1961, went to CDC first and then to Africa in 1965. We intended to spend our life there, but a civil war broke out between Nigeria and a breakaway region that named itself Biafra. The Biafra and Nigerian Civil War, and our medical center was overrun in the first weeks of the war that we had to flee. I went back then to work in the relief action in 1968. That war went on until the early 1970s.

I always intended to go back, but after years of working now in smallpox at CDC, I was so enamored with the idea of smallpox eradication, I couldn't leave. I continued then in CDC on smallpox eradication.

Lucas Perry: On this timeline, where do the efforts with regards to the WHO to begin having conversations about a possible smallpox eradication program, where does that fit in?

William Foege: Well, in the late 1950s, the Soviet Union began pushing who to do this. Dr. Zhdanov and others that the Soviet Union came in with a proposal. The very first vote at WHO only three countries agreed to get into a smallpox eradication program. Then the Soviet Union found that by joining up with the U.S., this increased the force and the U.S. and the Soviet Union together we're able to get WHO in 1964 to agree to this. At first there was no money. It was not until 1966 that they allocated money for smallpox eradication and so the program in West and Central Africa began in January of 1967.

Lucas Perry: Okay. You're working in Nigeria before the WHO has commenced this program.

William Foege: That's correct.

Lucas Perry: Then once Zhdanov helps to push this program through, you're then funded and the area for which you're working on smallpox increases throughout West Africa.

William Foege: 20 countries of West and Central Africa. From Senegal all the way over to the CAR, the Sahel countries, Mali, Niger and so forth, right down to the ocean with Ghana, Nigeria, Togo, it's now Benin, and so forth.

Lucas Perry: What was your involvement in the WHO specifically in terms of the strategy for smallpox eradication?

William Foege: Well, the head of the smallpox program at CDC right at the beginning was D.A. Henderson. D.A. Henderson was then seconded from CDC to WHO in order to start the global program. The CDC was asked to take this 20-country area of West and Central Africa because initially people thought this would be the most difficult place in the world. They had the highest rates of smallpox, poorest communications, poorest transportation. I think that there was some idea at WHO this couldn't succeed. There were lots of people at WHO that didn't really want it to succeed.

They had been burned twice with the idea of eradication programs. The first time with yellow fever, where they instituted a eradication program, only to find out that the yellow fever virus was prevalent in primates in the forest. Short of being able to figure out how to vaccinate primates, you simply could not contain this with the vaccination of people only. That program was stopped. Then they had a program for malaria eradication and they were simply too early.

The technology wasn't there, the ability wasn't there, so they spent a lot of effort on malaria eradication, but were not successful. Now comes a request to try a third eradication program and there were many people who had no interest in this at all. Some of them actually were hoping it would not succeed. I think that's one reason that they gave CDC what they regarded as the most difficult area in the world. Of course, the surgeon general of the United States years later said the CDC people who went to do that were so young that they didn't know they couldn't.

That's why it succeeded. That's partially true. They were very energetic zealots and nothing would get in the way. There were about 43 of them assigned to the 20 countries, both medical officers and operational officers. These were exceedingly hard-working people so the goal of five years was met early, and as I say, it was under budget. It turned out to be a great success, but now it gave the strategy for the rest of the world. That is, you don't have to go through the first part, which is to seek herd immunity.

You don't have to have a mass vaccination program. You can start right in the middle and find the virus. Then it becomes a battle between you and the virus. Are you good enough to find the virus and figure out who's at risk now? Not who's going to be at risk in nine months.

Lucas Perry: Right. I think the jargon for this is surveillance and containment?

William Foege: Correct.

Lucas Perry: Surveillance and containment has demonstrated to be successful in West Africa and so then this is going to get implemented throughout the world to finish off the smallpox eradication program. Can you take us to that larger worldwide perspective in places like India and Southeast Asia, where smallpox is still widespread and where we are on this timeline?

William Foege: Yes. The year after West Africa became free of smallpox, Brazil became free using the same technique of surveillance-containment. In 1973, most countries in Asia had become free except for Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan so now we could concentrate on those countries. The concentration in India started in October of 1973 and the same for Bangladesh. The amount of smallpox in these countries was so great. We were not sure that this new approach could actually work.

In October of 1973, we did our first pilot of trying to figure out, could we do surveillance in a way that you could go to villages and find out very rapidly whether they had smallpox? We tried in four different states to do this. I was so naive that the instructions that I wrote for doing the search indicated we won't find much smallpox because it's the low season of transmission of smallpox, but we're going to learn how to find smallpox. We're going to learn the technique going to the village, who should we be talking to? What should we do when we're there?

To my great surprise and horror, I might add, six days later in just two states, which are Pradesh and Bihar, the searchers had found 10,000 new cases of smallpox that we didn't know about. Suddenly we're overwhelmed. There's no way we can respond with containment to that many cases of smallpox. There were some people that suggested, "Let's never do this again. It's finding too much smallpox." Well, it's finding too much smallpox because this is the best surveillance we've ever done, and we're going to keep doing it and we'll do it every month. That's what we did.

Every month we took six days to search and to find what we could find, and every month we got better at it. Instead of just talking to school teachers and maybe the village chief, and maybe some school children, we started going house by house, asking people if they'd seen smallpox. Each month, the searchers would have to put a mark of some kind on the door that was changed every month, but it allowed a chalk mark so that the people doing the appraisal afterwards could estimate what percentage of houses were actually visited.

The search really became very good, but we weren't satisfied with that. We did secondary surveillance in marketplaces, and again, asking people if they've seen smallpox. We set up tertiary surveillance systems in areas likely to have smallpox such as bigger communities or people working on brick hills, where they would move from village to village. Surveillance in about six months became exceedingly good. Containment was more difficult because we had a much bigger job than what we anticipated. At first, we couldn't even get to all the villages that reported smallpox.

The ones we did get to, people would vaccinate the household and a few houses around and then move on to the next place. As we got better and were able to hire more people, we could do a larger ring around every affected person that had small box. There were so many people you could not send them to a hospital so you quarantined them at home. That meant we had to have watch guards at the house, not so much to keep people from visiting, but to keep people from visiting who were not vaccinated.

We had learned in Africa that if you vaccinated a person, the day they were exposed, they would be protected. Anyone that came to visit the sick people, we would vaccinate them before they would go to the house and they would not get smallpox. You have to have two watch cards because the first one has to take breaks, has to go to the bathroom and has to go get food. That sort of thing. If you have two, you need at least four, even if they work 12-hour shifts, and maybe you need six people in order to have eight-hour shifts. It required a lot of people.

In May of 1974, where surveillance was now really at a very good level, containment was beginning to improve. When Bihar reported 1500 new cases a day, that meant 1500 new investigations a day. It meant hiring new watch guards. At one point I think we had about a hundred thousand watch guards on our payroll. It was a big operation. As I say, we went from those high rates to zero in 12 months' time. The system worked, it just took a while to perfect it. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh were the big ones in the early 70s.

By 1975, we had finished in May in India. By that fall, Bangladesh had finished, Pakistan had finished and so now we had the last case of Asian smallpox in the fall of 1975. Now, the only part left in the world is Ethiopia. Ethiopia is a very difficult country to work in for lack of roads and very difficult terrain. Now we could concentrate on that. Ethiopia had a strain of smallpox that did not have high death rates and so you can understand that they were less interested than a country like India.

In India, 30% of people getting smallpox would die. In Ethiopia, it was just one or 2% would die and so you can see why it would be difficult to get their interest. Now that they were the last country in the world, a lot of people put a lot of resources, even bringing in helicopters in order to finish Ethiopia. Ethiopia finished and people started celebrating that this was now the end of smallpox in the world, only to learn that in that last week of smallpox in Ethiopia, it had somehow migrated from there to Somalia.

Somalia was a difficult country, always at war internally, not a safe place to work, but now we had to concentrate on Somalia. It took several more years to finish Somalia. Then that was the end of smallpox in the world. We thought. What happened next? There was a case of smallpox in Birmingham, England that came from a lab and it infected a woman that worked in the story above the lab. She was a photographer. She ended up in the hospital and they had some trouble making a diagnosis at first because no one was actually suspecting smallpox and she eventually died.

Her father came to the hospital, had a heart attack and he was admitted as a patient and he died. Then her mother got smallpox, but her mother recovered. That turned out to be the end of smallpox in the world, but it took that odd twist at the end. When you think that the answer to smallpox started in England in 1796, and now the last case in the world ends up in England also, the irony of that is really something.

Lucas Perry: The Birmingham case is because there was smallpox in the lab and so there's this distinction we can make between the last naturally-occurring incidence of smallpox and the last lab escape version. I wasn't aware of this less fatal variation on smallpox that was in Ethiopia and Somalia. I thought I heard somewhere that the last case of maybe the more fatal version was in Southeast Asia?

William Foege: That's correct. In Bangladesh. On the 30th anniversary of smallpox eradication in India, I was invited back to give a talk, which I did and met that last case. She was now a mother and her husband came, who was a farmer in Bangladesh, and so for me, it was a nice completion of the circle to meet her.

Lucas Perry: That concludes the first portion of my conversation with Bill Foege. Now I'm happy to introduce my conversation with Michael Burkinsky as well as Victor and Katia Zhdanov. I'm really happy to have you guys here. I'm really grateful for this opportunity and to be able to learn more about your lives and the life of Viktor Zhdanov. Could you guys just start off by explaining the family structure and we can also have you introduce yourselves?

Michael Burkinsky: I'm a stepson of Viktor Zhdanov. My mom married him when I was about 11 or 12. We lived for some time before Victor was born, so Victor can say a little more about what he remembers.

Victor Zhdanov: Well, then I was a little boy, because I don't remember much, but my memories maybe start when I was five years old or four years old. Every weekend we went to our country house from Friday to Monday morning or to Sunday evening, then went back. Then I went to school.

Katia Zhdanov: That's all you remember?

Victor Zhdanov: Almost.

Lucas Perry: Victor, when were you born in relation to when Viktor Zhdanov was introduced to Michael's life?

Katia Zhdanov: Victor is 15 years-

Victor Zhdanov: 15 years, actually. Yeah.

Katia Zhdanov: ... younger than Michael.

Michael Burkinsky: Right. It was probably three/four years after my mom married Viktor Zhdanov. Yeah.

Katia Zhdanov: It was second marriage for both of them. For Victor's dad and Michael's stepdad and Victor's and Michael's mom.

Lucas Perry: Right. Your mother's name is Elena?

Katia Zhdanov: Alissa.

Michael Burkinsky: A-L-

Lucas Perry: So your mother's name is Elena?

Katia Zhdanov: Alissa.

Michael Burkinsky: A-L-I-S-S-A. Elena is her name in the book because she wrote this book as if it's fictional, but all these people there who have different names, they are real people.

Lucas Perry: Hey, it's post-podcast, Lucas here. The book that Michael is referring to is by Viktor Zhdanov Sr's wife. It's titled Viktor Zhdanov, My Husband, Elena Tatalova's Diary. It covers much of his life from her perspective and gets into a lot of the events surrounding smallpox and the eradication efforts. All right. Back to the episode.

So Alissa and Viktor Zhdanov the father, they had a similar intellectual and professional background. Could you explain what that was?

Michael Burkinsky: Alissa was a scientist in the Institute of Virology and Viktor Zhdanov was the director of the Institute of Virology. My mom worked on Influenza and Viktor worked on different viruses including influenza so they had some common interests, but the main thing is that they were both very virologists.

Victor Zhdanov: That's how they met.

Lucas Perry: Both of you have also studied medicine, correct?

Victor Zhdanov: Correct.

Lucas Perry: Could you explain to me what your personal relationship is like with medicine and biology now and throughout your life?

Michael Burkinsky: Well, I pursued a career in medicine and biology, and specifically in virology. Victor switched to a different area.

Victor Zhdanov: Yeah, I prefer business actually. From the very beginning I was in business.

Michael Burkinsky: He went to medical school mostly not to disappoint.

Katia Zhdanov: The parents.

Victor Zhdanov: Correct.

Lucas Perry: Okay. I see. So let's stick with a bit more about your personal experience growing up in the family and what Victor and Alissa was like before we get into the actual work on eradicating smallpox. So I will start with you Michael. You were 12 at the time that Viktor Zhdanov was introduced to your life. What are your earliest memories and what was it like growing up with him and having two parents that were deeply embedded in quite academic scientific fields?

Michael Burkinsky: When my mom married Viktor, he was actually the Director of the Institute, so immediately I felt that he is a little bit far away from me in terms of his position. He was really a senior boss in terms of his social position and the stuff, he had a personal car for example, and in USSR at that time, a personal car was a sign of really very high position and stuff like that. So I was kind of scared of him in a sense. In the beginning, I didn't even know how to call him, so I didn't call any name. And then he started to kind of making contact with me, I guess, showing that he is not really a high above person, but a normal guy. He went with me to children's shows for example. Of course, we went together to the country house as Victor has said, and basically it started some kind of relationship.

In the end much later of course it was really pretty close, especially when I started working this virology field. But that was much later. He tried very hard to make my life comfortable. For example, when I was in senior classes in school, of course, as all kids do, you need some money to go places and stuff like that, and he never rejected. He would always give me whatever I asked for. Although I should say that he was very focused on his work, and the science, and business relations, so he didn't really have much time to talk to me and to spend with me. His days were extremely busy. He woke up early, went to work, came back late in the evening. And still after coming back, we had probably some meal together, but then he was again sitting down to write his papers, books, and stuff like that. So there was not much opportunity to communicate with him unfortunately. This is I think a big thing that we all missed.

So that's how it was in my childhood. But after then, the time came for me to choose the career. He was instrumental in deciding which school I should apply to. He helped me a lot with preparing for my exam to medical school, and it's mostly because of him that I got into this medical school which I graduated from. He was really the key person who helped me with all my appointments, and a place to do my PhD studies. He actually advised me where to go because he knew all these paths and places. My mom also knew of course, but he had much more influence on me in terms of selecting the career path. And then the final input from him was choosing this HIV research as a career and that was exclusively due to him that I started this career path. Without him I probably would never do it.

Lucas Perry: This Institute of Virology, was it started by your stepfather, Michael?

Michael Burkinsky: Institute of Virology was the main virological research Institute in Moscow and in Russia in general. It was organized sometime before Viktor Zhdanov became the director, but it really flourished after he became the director. It became really a well-known place for research, not only in USSR, but all over the world. He was really instrumental in making this Institute well-recognized and known organization.

Lucas Perry: Right. So he later founded a Journal of Virology.

Michael Burkinsky: He founded it, yes.

Lucas Perry: Okay. So you say that he was extremely busy, which is quite easy to imagine. What is the home experience like for you then? You said you're not interacting with him much. Do you guys have the occasional dinner together? Do you have meals together? What are most of your conversations like? What are some of your favorite memories with him in general?

Michael Burkinsky: Victor may say maybe his experience, but with me, he was not involved in my homework or stuff like that. What I remember very well was meals together because sometimes he came back from work when my mom was not home, and then we had a meal together and I was hungry of course. I remember that he comes and says, "Oh, you're hungry. Let's make some food," and he started cooking. And this was really funny because his cooking was really a thing of, he could boil sausages, and then use the same water to make tea. He didn't pay much attention to these kind of details and this was more of a formal thing. You need to eat, you need to drink and do we'll do something, and that's what it is. He just looked at it very utilitarian.

Lucas Perry: So what was it like eating that food?

Michael Burkinsky: Well, I ate sausages. I didn't drink the tea that he-

Lucas Perry: You didn't drink tea water?

Michael Burkinsky: Yeah. I thought that that's really inappropriate. And I remember that sometimes funny things happened, like we had dogs at the country house and he sometimes cooked porridge for the dogs and then he could use the remaining of this porridge to eat himself. What he loved really was science and stamps. Those were his two hobbies, Science first and stamps second. And that's what he loved. He had a great collection, one of the biggest in Moscow. All the other things were really kind of secondary.

Lucas Perry: So you didn't think you would be doing HIV research if it weren't for him. You're currently at George Washington University, yes?

Michael Burkinsky: Yes.

Lucas Perry: And you've focused your career on HIV. You have many publications and many citations on that subject. What was his role in that decision, and what were his reasons, and what was his guidance?

Michael Burkinsky: Well, he was really instrumental here because at that time the epidemic had just started and it started in US, and in USSR, there were occasional cases, very few cases, but he envisioned that this would become a big problem for the world. And besides the virus itself was very interesting. It was a new virus that was discovered so he envisioned that this will be really a whole new area of science in a sense. And he told me that's probably what you should try to do, and that's extremely interesting and potentially very important. That's what I did, and I started in 84.

Lucas Perry: Do you remember his reasons?

Michael Burkinsky: His reasons were that it is a disease that will really affect a lot of people, on all continents, in all countries, and will be potentially a very serious healthcare problem. That's one thing. But second is that it's a very interesting scientific problem also. So it has both things that are very attractive for a scientist, that you do interesting research, and you can discover a new biological phenomenon, and you are helping people.

Lucas Perry: All right. So Victor, what was your experience like?

Victor Zhdanov: Well, as Michael mentioned, my father was a high social position, but he never showed this. He really had his personal car, but he used it only on weekends to get to our country house. He act himself like a usual guy. He was fond of garden, and he was growing tomatoes, cucumbers, some fruits, some salads. That was his third hobby. Besides the science and postal stamps, the third hobby was the garden. All the weekend he spent in the garden. He did it himself. He didn't hire anybody to develop, but he did it all by himself. During the weekdays, he was really busy and he really, like Michael said, came home very late, and when he came home, he continued working on his articles, and my mother too.

They had two tables standing one to each other, and they were sitting and writing, siting and writing. Articles, articles, scientific books. I felt lonely mostly because not father, not mother almost didn't have any time to spend with me. The only time we spend together when my father and my mother, they took a break one month in the year and we went somewhere, Black Sea usually, two or three weeks. That was the time when we were together.

Lucas Perry: So you mentioned that your mother was also working on articles. Could you explain what your mother's position and academic interests were, and what her science life was like?

Victor Zhdanov: Well, she was chief of laboratory in the same Institute where my father was director. She was also professor.

Michael Burkinsky: Yeah. She was teaching at the college for doctors. There was a college where practicing physicians could learn some science.

Victor Zhdanov: Yeah. Upgrade the skills and she was teaching there. That was her second job.

Lucas Perry: Okay. So I guess I'm a bit more interested also on what's actually in your houses. Are there lots of books? In the diary it seemed like there was all this experiment stuff in the houses, and when it overflowed at one house, that the overflow got moved to the country home. What does the actual house look like?

Victor Zhdanov: We had an apartment in Moscow and the country house was also filled up with the books, with his articles, with the pictures of viruses. Viruses were everywhere, in Moscow apartment and in country house as well.

Lucas Perry: So I'm just imagining an apartment, there's tons of papers and books stacked, and there are also prints of viruses from microscopes on the walls or.

Michael Burkinsky: There was this office where the tables stood side by side. On the wall near his desk where he was sitting and writing was a collection of his souvenirs that he brought from all over the world, from the countries that he visited at some point. So it was like 50, 60, 70 different souvenirs, just little things that he brought from foreign countries. And he hang them on the wall in two or three rows. This took a lot of wall space. Then there were shelves filled with books and that's where all their writings went until they overflow and then it was taken to the country house.

Lucas Perry: So Victor continuing with a bit of your life experience there, so your parents are both incredibly busy, you're going between the Moscow apartment and the country house, is there anything else you want to add about your life experience up until you're about 18? How do you end up in America? And are there any other funny or interesting stories you have about growing up with your father or any other favorite moments?

Victor Zhdanov: This lasted for, not 18, he passed when I was 16. I had just finished school when he passed. And then during when I was passing my exams, he died. And my mother and my brother, they didn't tell me because they told me I need to pass my exams. I was in process of my exams in college. And so they considered that I need to concentrate on it, and only after I passed my last exam successfully, my brother Michael, he picked me up from my exam, and while he was driving me home, he told me this story that my father died and it was already a week or two ago, and so they didn't tell me this.

Lucas Perry: Was his passing sudden?

Victor Zhdanov: To get the stroke, the stroke was sudden, yes. He had a bad heart. He was ill, but he was still working. And this attack, it came suddenly. He had couple of them before, but they were not that serious as the last one. The doctor was called and he was taken to hospital where he stayed like a week or two and then he died.

Lucas Perry: So as we kind of wrap up on this more personal side of your experience with your father, I guess I just want to offer a little bit of space in case anything else comes to your mind if either of you guys want to add anything before we move on.

Michael Burkinsky: Well, I just want to say that it sounds as if he didn't pay much attention to us at home because he didn't have time, or was too busy, and all these things, but he was extremely attentive in terms of if we needed something, he was always there to help. He could throw away his work, and make phone calls, and make arrangements, and things like that. Or whether we had a problem at school, or at the college, and in personal problems, probably not so much. We just didn't, at least I didn't really go to him with my personal things too much, but he was an extremely warm person, warm and kind, and tried to help. And I think that he was teared between his main interests, and his feeling of his obligations towards greater human, let's put it this way, human need and his family interests.

He was an extremely kind, and warm, and helpful person. And maybe he didn't express it too much but now I realize that he really was.

Victor Zhdanov: Michael mentioned that he was the higher social position, but he acted himself like a simple man. For example, he had government car with personal driver besides his own car, but he often went to work using just regular bus. He could eat in restaurants but he ate in the street dumplings place. He also had a lot of friends who visited us, and I and my mother, we were fond of mushroom hunting. In the United States it's not popular, but in Russia, it's very popular. Gathering mushrooms in the summer, and he also went with us. There's some mushrooms, they are with worms. Well, we usually throw away these mushrooms, but he did say that they're also edible. And he marinated, and then when his friends came, he put these mushrooms on the table, with some worms on the button.

Lucas Perry: Wait, what?

Katia Zhdanov: Because he was very high position, his friends or people visiting him, they couldn't-

Victor Zhdanov: Refuse. They couldn't refuse eating it.

Katia Zhdanov: They couldn't refuse.

Lucas Perry: That's hilarious.

Katia Zhdanov: So they would actually eat it. But that's what he did.

Victor Zhdanov: He ate himself as well.

Lucas Perry: Did he remove the worms from the mushrooms?

Michael Burkinsky: No. The worms were there. People didn't have to eat them of course. But they were there, and you could just put them aside.

Victor Zhdanov: His friends called it mushrooms with meat.

Lucas Perry: Okay. So they knew that it had worms in it?

Victor Zhdanov: Of course, of course. And he knew, but everything was marinated, and worms also. And he ate it himself. He didn't eat the mushroom that we prepared with my mother, he prepared himself and ate his own mushrooms, and also his friends.

Lucas Perry: Oh, that's hilarious. That's a really good story. Thanks for sharing.

Between the mushroom worms and the sausage water, did you guys have anything else like that before we move on? These are pretty gold.

Katia Zhdanov: They keep saying that they didn't spend much time with the father but Victor told me some stories, like his father bringing him some presents from different countries, which was very rare. Back in USSR bringing in something from out of the country, it was really exclusive. So, and also the car that your cousin?

Victor Zhdanov: I wouldn't say cousin, Michael's wife's brother, we're the same age approximately. My father was teaching me to drive the car when we were in our country house. Starting from, I think then he was teaching me to drive the car so I was driving. And once we took the key and stole this car.

Katia Zhdanov: They decided to go for a ride without [crosstalk 00:48:22].

Victor Zhdanov: Little bit, little ride like maybe 500 meters back and forth-

Katia Zhdanov: Without letting the adults know that they're taking the car.

Victor Zhdanov: And then we got stuck in the woods for an hour and they were all searching for us. We were afraid to come back and say, "We're stuck in the woods because we cannot move the car." And finally a group of tourists helped us. They pushed the car out of the mud and then we decided, they're already searching for us, they're already angry with us, let's go ride for the highway. And we went to highway and I remember I was spinning like 80 miles.

Katia Zhdanov: And you were 10?

Victor Zhdanov: I was I think 12.

Lucas Perry: Is that how fast you're going, or how far you went?

Victor Zhdanov: How fast.

Katia Zhdanov: How fast.

Victor Zhdanov: It's really fast for me, for a 12 year old boy.

Lucas Perry: Yeah.

Katia Zhdanov:And obviously when they came back, the parents already called the police so they were already searching for them. So you can imagine they got in big trouble.

Victor Zhdanov:Father didn't talk to me for several days after that.

Lucas Perry:Wow. Yeah. Thank you for sharing all of these. Let's pivot here into a bit of the more narrative story of the actual smallpox efforts. Where do those smallpox efforts start? And then it'd be great if you could take us through how Viktor Zhdanov was involved in the efforts for smallpox eradication and what his role there really was.

Michael Burkinsky:So smallpox eradication started in 68 so this was quite a long time before my mom married Viktor Zhdanov so this was a pretty long time before the things that we discussed so far. It started when Viktor Zhdanov was a Vice Secretary for Health Affairs in USSR. At that time, he was not really doing science. He was an administrator and he was a high level administrator. He introduced today's program of eradicating smallpox using vaccines to the Assembly of World Health Organization in 68. And this was accepted and it took about 10 years, I believe to eradicate smallpox all over the world. So in 78, this program was completed. I only know about that from records and I didn't have any personal experience with that part of his career. He spoke about it occasionally, with us, and with his guests, just remembering about these times, but he never put it as a front accomplishment of his life. And he always thought that he would do much more. Although in the hindsight, it is clear that this was his major contribution to humanity because it really saved in a measurable number of lives.

But after that, he contributed a lot to HIV prevention and the cure efforts to Influenza, pandemic, relief, and many other things which are related to those worldwide pandemics, epidemics, and I think that based on his initial experience during that time of smallpox, that helped him a lot in these future efforts.

Victor Zhdanov: Yes, of course. I cannot tell nothing about his role while I was not born, but I remember that once he returned, I think from Geneva, and he was awarded with the Bifurcated Needle award, he was very proud of it. He proudly put it on the wall or somewhere.

Lucas Perry: All right. So with regards to his actual efforts in relation to smallpox, the central contribution here is convincing the World Health Organization to take up this smallpox eradication program, which then effectively eliminated smallpox from the population. Do you guys have any insights into how he got interested in that or more of the details about his experience leading up to that presentation to the WHO about the need for smallpox eradication, or any of the details of him convincing members of the WHO to take it up?

Michael Burkinsky: Well, this program of smallpox vaccination was introduced in the USSR sometime before this session of the WHO. The program was extremely successful in USSR, and basically the number of infections dropped dramatically and eventually disappeared. So his idea was to expand this to the whole world basically. And what actually put him towards this idea, I cannot say, but he was a physician by training. He gradated from the medical school and was always interested in curing disease, so when he got to a position where he could influence world health, I think this was logical for him, natural for him to try to implement things like this program that would cure and eliminate the scourge, the smallpox, which was killing millions of people.

He was always, during his whole life as I remember, very interested in approaches to cure and eliminate infectious diseases, whether we talk about smallpox, polio, influenza, hepatitis, he was involved in many, many different diseases and infections, and specifically in viral infections, of course. And I think that that was very natural of him to propose this vaccination and a smallpox elimination program.

Lucas Perry: So something significant that you mentioned was that Russia already had a program for widely vaccinating the population against smallpox.

Michael Burkinsky: Correct.

Lucas Perry: And so perhaps that served as some kind of example of what should be done for the global community.

Michael Burkinsky: Absolutely, yes.

Lucas Perry: Okay.

Michael Burkinsky: His contribution was huge to many different elimination, or cure, or vaccination efforts. In some, he played the leading role like in HIV/AIDS efforts in USSR. In some, he was more in that secondary, like in polio vaccination, but he was actually a friend of Sabin, the author of the polio vaccine, and he invited Sabin to Moscow. Influenza vaccine for example program was one of his main interests because influenza studies were actually the main focus of the Institute of Virology for some time. So he was really instrumental in a number of vaccination, and cure, and other efforts. He was really a great virology figure, not only in Soviet Union, but I think worldwide.

Lucas Perry: All right. Finishing up here, could you expand a little bit on the specifics of what he exactly proposed at the WHO?

Michael Burkinsky: The vaccine scene was present. Scientifically everything was in place. So the only thing that was needed was a cooperation between the countries to implement the vaccination strategy around the world. And this required agreement between the health officials from all countries, and as we know, and we can see it now, with this Coronavirus vaccination, that's not an easy task. It requires a lot of administrative and medical arrangements, and that requires commitment on the governmental and local levels. He was able to really put it together, basically, to convince all the people present at this meeting to sign the agreement and basically commit to implementing this vaccination in their respective countries.

Lucas Perry: So it's this massive coordination effort to first of all, implement surveillance of where the virus is, and then containment. To some sense of there being a limited amount of vaccines, and so instead of just giving it to everyone in the world, you find where the smallpox is, and then identify everyone that's interacted with that person and then vaccinate everyone around there. And so with a limited amount of vaccine, you can effectively stamp out the fire of smallpox by causing a cessation of the spread and so then it dies.

Michael Burkinsky: That's correct, but it also requires production of the large number of vaccines. Ideally you want to really have total population being vaccinated rather than counting that maybe we will vaccinate half of the people and the virus will kind of disappear. At least in USSR, they vaccinated all children who were born. This was an obligatory vaccination strategy, and I believe this was an obligatory vaccination with a strategy and I believe it was accepted all over the world that that's the way to do this. You need to vaccinate everybody at least only new born children. Not everybody agreed with this strategy because I mean it's expensive of course, it's difficult and it's not a commonly accepted thing at least especially at that time.

Lucas Perry: All right. So, let's talk a little bit about your mother and the book which she wrote titled, "From Viktor Zhdanov My husband, Elena Tatulova's Diary," sorry for butchering that, diary. You guys mentioned already that this is fictionalized to a certain extent. Can you explain why it's fictionalized?

Michael Burkinsky: I don't know. I guess that she didn't want to put the real names there to avoid potential problems with people being in contempt with her recount and things like that. Although I should say that what is written in the book is pretty close to reality and I can recognize all the characters there. I suppose that that's one reason and the second was that when she wrote it I think she saw it more as a love story if you want, rather than just a memoir or remembrance of Viktor. She thought that it would be more interesting for readers who do not know Viktor's down to four people around him and maybe they will be just interested in reading a story in general about a scientist, his wife, and things like that.

Lucas Perry: So I'm going to share some extracts that I liked or found interesting and then you guys can react to them if you'd like, this is a translation from the Russian so it's not totally perfect right now. Alyssa is mentioning that she found shortly after the death of your father in his journal, this kind of frustration around his work. She finds his journal entry in his office and it says, "I stopped working in the laboratories of course there is an excuse. I'm too busy working as the director but I don't accept my own excuse. That is laziness inertia, how I hate myself for it. So much effort has been spent in vain and now I have no strength left no time for real science. I did not do what I should have and could have done with my life." She then goes on to say, "He could have done a lot, move mountains, find a new code of life, invent a cure for all viral diseases but for that, the brash fearless and selfless person that Viktor Zhdanov was should have been born at a different time or place."

Michael Burkinsky: He was always discontent with himself. He always felt that he should do more and that's the reason why he was spending so much time at work and writing and he was always thinking that he did not do everything that he could, that's his nature but he had a lot of obstacles and was always a target for all those people who tried to diminish him, tried to discredit him. The first year was very tough, it wasn't competition. Competition might be healthy but this was not a healthy thing, it was more of an atmosphere where people used all the means to discredit him. Writing anonymous letters to those administrative organizations, making all this nasty phone calls and this was really unhealthy and difficult situation which definitely prevented him from being more productive and more purposeful.

Lucas Perry: What was the incentives or motivations for people to be disparaging?

Michael Burkinsky: Motivations were he usually either due to his ideas and that was on a kind of regulatory levels. For example, he wanted to establish close collaborations with the Western scientists and empower exchange of people, ideas and things like that and this was against the policy of the government.

Victor Zhdanov: KGB was everywhere at this time.

Michael Burkinsky: That was one of the things, another was his ideas of which people should actually be promoted and demoted and what should be the incentives and stuff like that. That always causes some tensions in particular for people who are in high positions. So if he wanted to promote somebody who was a Jew for example, this immediately caused tensions with the central communist party officials, things like that so there was a lot of regulations that he was fighting against.

Lucas Perry: Yeah. It seemed like somewhere in the journal he's quoted as saying something like, "Science knows no borders." So he's having a conversation with someone who is kind of reacting to this call from him for this global interdisciplinary approach to science and virology specifically. So, here's another one that I quite liked. It says, "Soon, his conflict with the minister worsened, Viktor with his big sense of humor celebrated our son's first birthday with an article in an American magazine signed Zhdanov and Zhdanov Jr with thanks to Elena Tatulova for her technical assistance. When the minister found out about this he flew into a rage, can such a frivolous person be the director of a major scientific institute?" He asked. I thought that was quite funny and I think shows a bit of his humor and the juxtaposition between that and the overly strict ministers and bureaucratic figures that surrounded him.

Michael Burkinsky: Yeah he was extremely happy when Victor was born. Maybe a formulate was not the proper thing, but especially at that time, it was not a really big offense.

Lucas Perry: Yeah. I think I've got one more here for you it says, "The classification and evolution of viruses was a favorite problem of Viktor, a hobby that he devoted his evening hours to. He worked for many years on the fifth monograph evolution of viruses, which is one of the most voluminous and fundamental monographs on this problem. He believes that the evolution of the organic world and the evolution of viruses as one of the forms of life that went in parallel. Humanity would be different if the evolution of life took place apart from the evolution of viruses." I thought this was interesting it shows that he's thinking quite broadly and deeply, I think about the human condition and how it came to be.

Michael Burkinsky: This was his interest from the very early times in his career and he was a member for many years of this society devoted to classification of viruses and things like that. He wrote also several books about viral evolution and its evolution in the context of human evolution. So, he was very interested in this topic. Besides working on specific viruses he also was really thinking globally and widely about viruses. There was a long argument about whether viruses are alive or dead. He was always arguing that the viruses are a form of life, so they definitely are alive. So, that's how it came up.

Lucas Perry: All right. Is there anything else that you guys would like to finish up on here?

Michael Burkinsky: The only thing that I want to finish up with is that I don't think he is fully recognized for what he did to the world and to the Russian science and Russian virology in particular. I think that that's a shame and I hope that this award that he is getting now would actually push people especially in Russia now to consider better his great accomplishments and contributions.

Lucas Perry: Yeah, totally agree. I mean, he played a necessary role in eliminating something which had taken hundreds of millions of lives. For that we're eternally grateful and I do hope that the award helps to elevate awareness around his contribution and the history of smallpox and global health. So thank you guys so much for coming on and taking all this time to speak with me. It's really been a pleasure and I've really loved hearing all of these fun little anecdotes. So yeah, thank you so much and I'm excited to see you guys at the award ceremony.

Michael Burkinsky: Thank you Lucas.

Victor Zhdanov: Thank you.

Katia Zhdanov: Thank you.

Lucas Perry: And with that, I'd like to reintroduce my conversation with Will Foege. Here we explore the history of smallpox as well as biology in the 21st century. So, I'm interested in getting into the lab side of things and why labs might be holding onto smallpox. I'm also interested here in a bit of the actual history of smallpox so going back maybe a few thousand years. I'm curious if you can give the estimated time at which we think that smallpox arose, how many lives we estimate that it's taken over the 2000 years that it's been around and if you could also introduce the concept of variolation and how variolation was discovered and implemented, and then how it led to a vaccine, I think that'd be interesting.

William Foege: Okay. The history of smallpox it goes back thousands of years, but we don't know how it started or where it started. We do know that Ramesses V probably had smallpox because you can see there's pock marks on his face and we actually attempted to get specimens to see if we could grow smallpox from the skin lesions that he had. So it goes back a long ways. It for some reason, did not come to the Americas though and so it was a disease of China and Asia and Africa and Europe. But you get some idea of how prevalent it was because Voltaire had smallpox and became interested in it and he estimated in his lifetime that about 60% of all children born in Europe would end up getting smallpox and he said of those 60%, a third of them will die, a third of them will be scarred for life and only a third will get away scot-free with this. So that's how common it was and you look back and Mozart had smallpox, Mozart's sister had smallpox.

You saw great changes in the Royal families because of this from smallpox, Louis XV died of smallpox. It was a very common disease. Then Europeans brought it to the Americas and in the Americas there was no immunity. Sometimes with a disease it's dependent on the individual immunity. But sometimes as with smallpox you always have a bell-shaped curve if some people are more resistant to a disease than others and so if smallpox is killing a fair number of people early on, the survivors may well have some natural advantage and therefore over time you get an immunity in the population. There was none of that in the Americas and so when smallpox came through it was very devastating. We know that the Blackfeet got smallpox even before Lewis and Clark made their visit. So in about the 1790s, there was a severe outbreak that took many of the lives of the Blackfeet. The Blackfeet were the most resistant tribe to having Europeans overrun their territory.

They were great fighters and except for smallpox they might well have kept the United States at bay for a long time. Sometime in history and we don't know when and we don't even know how people came across the idea that if you actually took the smallpox virus from the pustule or the sore on a person with smallpox and injected it into the skin of a healthy person, that the death rate was much lower than if they got it through natural means which is through the respiratory tract. I cannot envision how that happened that someone came across that because you don't know the exposure a person had whether it was through a skin lesion or inhaled you would need a number of people in each category to compare the risk of death. So I don't know how this developed, but it did and it may have developed in three different places over time in China, in India and in Africa.

We found out about variolation in this country about 1720. It was about this time that Lady Montagu, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, noticed that in Turkey they would take 20 or 30 school children at a time, take them to a remote farmhouse and they would variolate them. That is they would use smallpox virus to inject each child and over the next few weeks these children would get sick. Most of them would then recover without great damage and they could go back into their homes and be immune the rest of their life. The lady Montagu was intrigued by this and she wrote back to England about what she had observed. The Royal family in England then tried that on prisoners and they came to the conclusion that she was right, that you could spread smallpox and you would not have high mortality if you spread it skin to skin. So they tried that on prisoners it worked and they tried it then on their own children think of the leap of faith that they took there.

Well in England, it became an accepted thing to do and people were very elated by the tens of thousands and by the hundreds of thousands and their military was very elated. At just about the same time but by chance, the Boston area saw a smallpox outbreak. Boston only had about 10,000 people at the time but two or 3000 of them developed smallpox and Cotton Mather always a controversial figure, but a good scientist, a good observer noticed that the rate of smallpox was lower in African Americans than in whites. So he investigated, came to the conclusion that the African American slaves had brought variolation from Africa to America and when the first cases of smallpox appeared in Boston they started variolating in each other. So Cotton Mather wrote a pamphlet trying to get the U.S. to do this and it didn't catch on in the U.S. and I think part of this may be that Cotton Mather was such a controversial figure.

But anyway, if you now go ahead maybe 55 years to the Battle of Quebec during the revolutionary war, the American troops outnumbered the British two to one, and it should have been an easy battle for the Americans. They invaded on December 31st 1775, but a smallpox outbreak decimated the American troops, but the British troops were immune. So the British won that battle handedly and captured a lot of American soldiers and I sometimes say Canadians can thank smallpox for being part of the Commonwealth rather than part of the United States. But George Washington understood what had just happened and so he with his advisors talked about, we need to variolate American troops in order to have equal immunity to this disease and they did it very secretly because they were afraid if the British knew they were doing this that's when they would attack and he was successful in variolating the American troops and so as the revolutionary war headed south from New York down to Washington and down to Williamsburg and so forth, we now find that health-wise the British troops and the American troops were much more equal in their ability.

So I think this may have been the single most important tactical decision that George Washington made during the revolutionary war. So the idea of variolation, it comes from Variola which is the word for smallpox, vaccination comes from vaccinia the virus that's used for vaccinating against smallpox and so you have all this variolation going on, but now in 1796, Edward Jenner is asked by his mentor Hunter to try to figure out what it is that is happening with the spread of smallpox. And we're told that a milkmaid had mentioned to him, "I'll never get smallpox because I've had cowpox." And he decided to study what happens during outbreaks for milkmaids and he actually studied this for 12 years so it wasn't something he did on the spur of the moment and he came to the conclusion that yes milkmaids were in fact immune, if they had ever had cowpox. Now cowpox is a self-limited disease of the hands of the milkmaids. It's not something that they get systemically.

And so in 1796 in the spring, he finally did his big experiment where he made cowpox go from Sarah Nelms, a milkmaid to a boy James Phipps and then he later exposed James Phipps to smallpox, but James Phipps was immune. So that was the beginning of that structure. Now it took several years before he published for a number of reasons, but Thomas Jefferson was one of the first people to understand the significance of this and he was able to get smallpox vaccine through Benjamin Waterhouse in Boston and Thomas Jefferson went back to Monticello and vaccinated his household and his slaves and surrounding households so that they had immunity and then he wrote a letter to Edward Jenner and he said, "Future generations will know by history only that this lowsome disease has existed." And of course he was right. It took a long time to reach that point but then vaccination took off around the world.

But even with it being used around the world there were plenty of people who didn't get it, which explains why Abraham Lincoln got smallpox while he was president. So this is over 60 years after Edward Jenner had discovered the effect of cowpox and Abraham Lincoln had not had it. We only have one picture of him at the Gettysburg address and it's at such a distance you can't make out any real detail. But we're told by reporters that he looked very haggard and he was because he was coming down with smallpox at that time. They put him on the train, he got back to Washington DC early next day, one or two in the morning, went to the white house and that's where he stayed for two weeks. But the person taking care of him on the train developed smallpox from him and went on to die. So as late as the 1860s, it was still a major problem in this country and we had our last cases in 1949 due to an importation from Mexico.

Lucas Perry: So initially we're variolating and then there's this insight about the relationship between cowpox creating immunity to smallpox. Is that the vaccine or is that just a new kind of variolation?

William Foege: That is the vaccine.

Lucas Perry: Okay. That is the vaccine.

William Foege: That's right and recently,and I'm talking about just the last year or so, the history of cowpox virus has been elucidated so that I think now it's actually horsepox virus that we're using and it was horsepox virus that went to cows and moved from cows to humans and then from humans became the vaccine. So that the vaccine we use today is not cowpox it's something called vaccinia and it's probably related to horsepox different than we expected at the beginning.

Lucas Perry: Okay. I see. And so, what is the difference in efficacy between variolation and the vaccine? and what are the risks?

William Foege: With vaccine it's a very good immunizing agent and if you use potent vaccine, you should get a take rate or immune response in 95% plus of people so it's very good but it was also a very unsafe vaccine in the sense that in this country we were losing seven or eight people a year dying because of the vaccine itself and so it's the most dangerous vaccine that we've used. The vaccine was so dangerous that in the early 1970s, in this country we stopped using it routinely even though there was still smallpox in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, East Africa, we stopped using it because we had come to the conclusion we were so good at containing outbreaks that even if we had importations we could contain them with fewer deaths than if we continued to vaccinate. With variolation, if you're using a good virus and I'll say in a minute why you might not be using good virus, it should have been about the same that you would get a take at most people, but it was dangerous, like maybe a one or 2% mortality, so much higher than the risk of vaccine itself.

But in West Africa we found a group of people called Feticheur . They made their living on consulting with people who had smallpox and this was basically in an area that is Western part of Nigeria in what is now Benin into the Eastern part of Togo and if people had smallpox they came to the Feticheur and the Feticheur would give recommendations to the patient on what to do. It was a thriving business because if the person died, all the Feticheur had to say is I told him what to do and he wouldn't do it. But if the patient lived the family was so happy that they would give gifts to the Feticheur. But the Feticheur had learned that they could start outbreaks whenever they wanted to. They would take scabs from the people that they were seeing and they would keep these scabs in a bottle, in the coolest place they could. And those scabs would last for weeks or months.

And then if smallpox disappeared in the area they would make a paste with those scabs, put the paste on thorns and put the thorns on the inside of doorways and so that people going through some of them would inevitably get scratched and some of those would then get smallpox and that would start a new outbreak and continue their livelihood. In those cases, there was a point where you could not have viable virus anymore so that would be the equivalent of variolation but with low take rates. I should add that I spent a day with a Feticheur, I wanted to know what it is he knew about smallpox? What did he do in order to treat people? and why did they get smallpox? and his explanation was that they had all sinned, they'd done something wrong and this was the divine retribution for what they had done wrong. So I asked the question, "Well, what about children with smallpox at six months of age? What did they do wrong?" and they very quickly came back with the fact that the parents had done something wrong and so this was the equivalent of original sin.

Lucas Perry: Yeah. So what was the death rate of the actual vaccine? So you said seven people died from getting vaccine in one year. So it's like one in a million or something.

William Foege: It was probably less than one in a million because we were probably vaccinating several million newborns at that time and also vaccinating a certain number of adults who had never been vaccinated before probably close to one in a million but very low compared to variolation and very low compared to what happened if people got natural smallpox.

Lucas Perry: Compared to the vaccines that are normally distributed today, how does that compare? What is the death rate of a random vaccine we're given today?

William Foege: Smallpox was by far the most dangerous vaccine that we use. Vaccines have not only been quite safe, they've been getting safer all the time. For example, maybe the second most dangerous vaccine was for pertussis. Over the years you did not use pertussis vaccine in adults because they got such severe reactions. But now they have developed pertussis vaccine to a point where it does not have such severe reactions so most of the vaccines are just incredibly safe today and we have very few people who die from the routine vaccinations. You still have a few problems with encephalitis or other things, but they're so safe it's just unbelievable and compared to the disease, the vaccines are extremely safe.

Lucas Perry: Okay. And then you said that sometimes the virus might not be good or for example, in the case of those people in Africa who were intentionally infecting people to make money, maybe the virus wasn't good for some reason.

William Foege: That's correct because the virus dies over a period of time and the virus dies fastest with light and with heat and so in Africa you have trouble actually keeping it cold. If they kept it in a freezer it would last for years but they were finding the coolest place, a good underground as cool as it could be, but it would eventually go on to die so you can't under those conditions keep a virus living for an extended period. With the last case of smallpox in that area, Feticheurs came from all over trying to get scabs and that poor person was just denuded of scabs, but they were not able to pass it on after that and so it died out and the Feticheurs in general went to chickenpox where the survival rate was so great that they'd look good, but they no longer had a business with smallpox.

Lucas Perry: And so when they took the thorns and put them on the inside of doors to scratch people, I mean the point is that that was basically variolation right. Why does that infect people?

William Foege: Because if enough people go through that doorway and enough people get scratched and if the virus is still viable, someone is going to end up getting smallpox and then that starts the chain again.

Lucas Perry: Oh. So variolated people can spread smallpox?

William Foege: Exactly and that's why they would keep the 30 children at the farmhouse in Turkey until they'd all recovered.

Lucas Perry: Okay. That's the missing link, obviously with the vaccine, you can't spread it when you get vaccinated.

William Foege: That's right. Now there are cases of people spreading the virus from the vaccine to someone else and you can see how that would happen with vaccinia that was on the arm of the person and they touch that and then they touch someone. Vacccinia is not good for people who have eczema. For instance, people with eczema were usually excluded for vaccination programs because the virus could then spread in the area of eczema and cause real problems. So you couldn't get some spread of vaccinia virus but it was not that common.

A virus is a curious organism it cannot reproduce itself and so the only way it could reproduce is to get into the cell of a person or an animal or a plant and they're all very much attuned to certain species in certain plants that the nice thing about smallpox is it does not infect other species and so that's why it was possible to eradicate it. If had been a virus easily spread among other species as yellow fever was, there would have been no chance of doing eradication. The vaccine is made up of vaccinia virus and it is a little bit obscure what that virus really is but it appears it came from horsepox to cowpox into humans and mixtures along the way finally ended up with vaccinia which is the vaccine that's used around the world.

Vaccinia, which is the vaccine that's used around the world. Now, one of the things that they had done over the years, in India they used what was called a rotary lancet. And it was spikes around a central core. They would dip it in vaccine, put that on the skin and then spin it and you'd get a big sore because their feeling was it increased the chance that the virus would actually take. And just to be sure they would do this on three different places. So if they were using vaccine that was good, these people would end up with horrendous scars. If the vaccine was not good, they wouldn't end up with anything. So the reason they were using it was because they were not getting a 100% take rates. And the reason for that was because the vaccine wasn't good, not because they weren't doing enough scarification of the skin.

Lucas Perry: Okay. And I guess one last question on this is, what makes a good vaccine?