Should AI Be Open?

Contents

POSTED ON DECEMBER 17, 2015 BY SCOTT ALEXANDER

I.

H.G. Wells’ 1914 sci-fi book The World Set Free did a pretty good job predicting nuclear weapons:

They did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands…before the last war began it was a matter of common knowledge that a man could carry about in a handbag an amount of latent energy sufficient to wreck half a city

Wells’ thesis was that the coming atomic bombs would be so deadly that we would inevitably create a utopian one-world government to prevent them from ever being used. Sorry, Wells. It was a nice thought.

But imagine that in the 1910s and 1920s, the period’s intellectual and financial elites had started thinking really seriously along Wellsian lines. Imagine what might happen when the first nation – let’s say America – got the Bomb. It would be totally unstoppable in battle and could take over the entire world and be arbitrarily dictatorial. Such a situation would be the end of human freedom and progress.

So in 1920 they all pool their resources to create their own version of the Manhattan Project. Over the next decade their efforts bear fruit, and they learn a lot about nuclear fission. In particular, they learn that uranium is a necessary resource, and that the world’s uranium sources are few enough that a single nation or coalition of nations could obtain a monopoly upon them. The specter of atomic despotism is more worrying than ever.

They get their physicists working overtime, and they discover a variety of nuke that requires no uranium at all. In fact, once you understand the principles you can build one out of parts from a Model T engine. The only downside to this new kind of nuke is that if you don’t build it exactly right, its usual failure mode is to detonate on the workbench in an uncontrolled hyper-reaction that blows the entire hemisphere to smithereens. But it definitely doesn’t require any kind of easily controlled resource.

And so the intellectual and financial elites declare victory – no one country can monopolize atomic weapons now – and send step-by-step guides to building a Model T nuke to every household in the world. Within a week, both hemispheres are blown to very predictable smithereens.

II.

Some of the top names in Silicon Valley have just announced a new organization, OpenAI, dedicated to “advanc digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole…as broadly and evenly distributed as possible.” Co-chairs Elon Musk and Sam Altman talk to Steven Levy:

Levy: How did this come about? […]

Musk: Philosophically there’s an important element here: we want AI to be widespread. There’s two schools of thought?—?do you want many AIs, or a small number of AIs? We think probably many is good. And to the degree that you can tie it to an extension of individual human will, that is also good. […]

Altman: We think the best way AI can develop is if it’s about individual empowerment and making humans better, and made freely available to everyone, not a single entity that is a million times more powerful than any human. Because we are not a for-profit company, like a Google, we can focus not on trying to enrich our shareholders, but what we believe is the actual best thing for the future of humanity.

Levy: Couldn’t your stuff in OpenAI surpass human intelligence?

Altman: I expect that it will, but it will just be open source and useable by everyone instead of useable by, say, just Google. Anything the group develops will be available to everyone. If you take it and repurpose it you don’t have to share that. But any of the work that we do will be available to everyone.

Levy: If I’m Dr. Evil and I use it, won’t you be empowering me?

Musk: I think that’s an excellent question and it’s something that we debated quite a bit.

Altman: There are a few different thoughts about this. Just like humans protect against Dr. Evil by the fact that most humans are good, and the collective force of humanity can contain the bad elements, we think its far more likely that many, many AIs, will work to stop the occasional bad actors than the idea that there is a single AI a billion times more powerful than anything else. If that one thing goes off the rails or if Dr. Evil gets that one thing and there is nothing to counteract it, then we’re really in a bad place.

Both sides here keep talking about who is going to “use” the superhuman intelligence a billion times more powerful than humanity, as if it were a microwave or something. Far be it from me to claim to know more than Sam Altman about anything, but I propose that the correct answer to “what would you do if Dr. Evil used superintelligent AI” is “cry tears of joy and declare victory”, because anybody at all having a usable level of control over the first superintelligence is so much more than we have any right to expect that I’m prepared to accept the presence of a medical degree and ominous surname.

A more Bostromian view would forget about Dr. Evil, and model AI progress as a race between Dr. Good and Dr. Amoral. Dr. Good is anyone who understands that improperly-designed AI could get out of control and destroy the human race – and who is willing to test and fine-tune his AI however long it takes to be truly confident in its safety. Dr. Amoral is anybody who doesn’t worry about that and who just wants to go forward as quickly as possible in order to be the first one with a finished project. If Dr. Good finishes an AI first, we get a good AI which protects human values. If Dr. Amoral finishes an AI first, we get an AI with no concern for humans that will probably cut short our future.

Dr. Amoral has a clear advantage in this race: building an AI without worrying about its behavior beforehand is faster and easier than building an AI and spending years testing it and making sure its behavior is stable and beneficial. He will win any fair fight. The hope has always been that the fight won’t be fair, because all the smartest AI researchers will realize the stakes and join Dr. Good’s team.

Open-source AI crushes that hope. Suppose Dr. Good and her team discover all the basic principles of AI but wisely hold off on actually instantiating a superintelligence until they can do the necessary testing and safety work. But suppose they also release what they’ve got on the Internet. Dr. Amoral downloads the plans, sticks them in his supercomputer, flips the switch, and then – as Dr. Good himself put it back in 1963 – “the human race has become redundant.”

The decision to make AI findings open source is a tradeoff between risks and benefits. The risk is letting the most careless person in the world determine the speed of AI research – because everyone will always have the option to exploit the full power of existing AI designs, and the most careless person in the world will always be the first one to take it. The benefit is that in a world where intelligence progresses very slowly and AIs are easily controlled, nobody will be able to use their sole possession of the only existing AI to garner too much power.

Unfortunately, I think we live in a different world – one where AIs progress from infrahuman to superhuman intelligence very quickly, very dangerously, and in a way very difficult to control unless you’ve prepared beforehand.

III.

If AI saunters lazily from infrahuman to human to superhuman, then we’ll probably end up with a lot of more-or-less equally advanced AIs that we can tweak and fine-tune until they cooperate well with us. In this situation, we have to worry about who controls those AIs, and it is here that OpenAI’s model makes the most sense.

But many thinkers in this field including Nick Bostrom and Eliezer Yudkowsky worry that AI won’t work like this at all. Instead there could be a “hard takeoff”, a huge subjective discontinuity in the function mapping AI research progress to intelligence as measured in ability-to-get-things-done. If on January 1 you have a toy AI as smart as a cow, one which can identify certain objects in pictures and navigate a complex environment, and on February 1 it’s solved P = NP and started building a ring around the sun, that was a hard takeoff.

(I won’t have enough space here to really do these arguments justice, so I once again suggest reading Bostrom’sSuperintelligence if you haven’t already. For more on what AI researchers themselves think of these ideas, see AI Researchers On AI Risk.)

Why should we expect this to happen? Multiple reasons. The first is that it happened before. It took evolution twenty million years to go from cows with sharp horns to hominids with sharp spears; it took only a few tens of thousands of years to go from hominids with sharp spears to moderns with nuclear weapons. Almost all of the practically interesting differences in intelligence occur within a tiny window that you could blink and miss.

If you were to come up with a sort of objective zoological IQ based on amount of evolutionary work required to reach a certain level, complexity of brain structures, etc, you might put nematodes at 1, cows at 90, chimps at 99, homo erectus at 99.9, and modern humans at 100. The difference between 99.9 and 100 is the difference between “frequently eaten by lions” and “has to pass anti-poaching laws to prevent all lions from being wiped out”.

Worse, the reasons we humans aren’t more intelligent are really stupid. Like, even people who find the idea abhorrent agree that selectively breeding humans for intelligence would work in some limited sense. Find all the smartest people, make them marry each other for a couple of generations, and you’d get some really smart great-grandchildren. But think about how weird this is! Breeding smart people isn’t doing work, per se. It’s not inventing complex new brain lobes. If you want to get all anthropomorphic about it, you’re just “telling” evolution that intelligence is something it should be selecting for. Heck, that’s all that the African savannah was doing too – the difference between chimps and humans isn’t some brilliant new molecular mechanism, it’s just sticking chimps in an environment where intelligence was selected for so that evolution was incentivized to pull out a few stupid hacks. The hacks seem to be things like “bigger brain size” (did you know that both among species and among individual humans, brain size correlates pretty robustly with intelligence, and that one reason we’re not smarter may be that it’s too annoying to have to squeeze a bigger brain through the birth canal?) If you believe in Greg Cochran’s Ashkenazi IQ hypothesis, just having a culture that valued intelligence on the marriage market was enough to boost IQ 15 points in a couple of centuries, and this is exactly the sort of thing you should expect in a world like ours where intelligence increases are stupidly easy to come by.

I think there’s a certain level of hard engineering/design work that needs to be done for intelligence, a level waybelow humans, and after that the limits on intelligence are less about novel discoveries and more about tradeoffs like “how much brain can you cram into a head big enough to fit out a birth canal?” or “wouldn’t having faster-growing neurons increase your cancer risk?” Computers are not known for having to fit through birth canals or getting cancer, so it may be that AI researchers only have to develop a few basic principles – let’s say enough to make cow-level intelligence – and after that the road to human intelligence runs through adding the line NumberOfNeuronsSimulated = 100000000000 to the code, and the road to superintelligence runs through adding another zero after that.

(Remember, it took all of human history from Mesopotamia to 19th-century Britain to invent a vehicle that could go as fast as a human. But after that it only took another four years to build one that could go twice as fast as a human.)

If there’s a hard takeoff, OpenAI’s strategy looks a lot more problematic. There’s no point in ensuring that everyone has their own AIs, because there’s not much time between the first useful AI and the point at which things get too confusing to model and nobody “has” the AIs at all.

IV.

OpenAI also skips over a second aspect of AI risk: the control problem.

All of this talk of “will big corporations use AI” or “will Dr. Evil use AI” or “Will AI be used for the good of all” presuppose that you can use an AI. You can certainly use an AI like the ones in chess-playing computers, but nobody’s very scared of the AIs in chess-playing computers either. The real question is whether AIs powerful enough to be scary are still usable.

Most of the people thinking about AI risk believe there’s a very good chance they won’t be, especially if we get a Dr. Amoral who doesn’t work too hard to make them so. Remember the classic programmers’ complaint: computers always do what you tell them to do instead of what you meant for them to do. The average computer program doesn’t do what you meant for it to do the first time you test it. Google Maps has a relatively simple task (plot routes between Point A and Point B), has been perfected over the course of years by the finest engineers at Google, has been ‘playtested’ by tens of millions of people day after day, and still occasionally does awful thingslike suggest you drive over the edge of a deadly canyon, or tell you walk across an ocean and back for no reason on your way to the corner store.

Humans have a really robust neural architecture, to the point where you can logically prove that what they’re doing is suboptimal, and they’ll shrug and say they don’t see any flaw in your proof but they’re going to keep doing what they’re doing anyway because it feels right. Computers are not like this unless we make them that way, a task which would itself require a lot of trial-and-error and no shortage of genius insights. Computers are naturally fragile and oriented toward specific goals. An AI that ended up with a drive as perverse as Google Maps’ occasional tendency to hurl you off cliffs would not be self-correcting unless we gave it a self-correction mechanism, which would be hard. A smart AI might be able to figure out that humans didn’t mean for it to have the drive it did. But that wouldn’t cause it to change its drive, any more than you can convert a gay person to heterosexuality by patiently explaining to them that evolution probably didn’t mean for them to be gay. Your drives are your drives, whether they are intentional or not.

When Google Maps tells people to drive off cliffs, Google quietly patches the program. AIs that are more powerful than us may not need to accept our patches, and may actively take action to prevent us from patching them. If an alien species showed up in their UFOs, said that they’d created us but made a mistake and actually we were supposed to eat our children, and asked us to line up so they could insert the functioning child-eating gene in us, we would probably go all Independence Day on them; because of computers’ more goal-directed architecture, they would if anything be more willing to fight such changes.

If it really is a quick path from cow-level AI to superhuman-level AI, it would be really hard to test the cow-level AI for stability and expect it to remain stable all the way up to superhuman-level – superhumans have a lot more options available to them than cows do. That means a serious risk of superhuman AIs that want to do the equivalent of hurl us off cliffs, and which are very resistant to us removing that desire from them. We may be able to deal with this, but it would require a lot of deep thought and a lot of careful testing and prodding at the cow-level AIs to make sure they are as prepared as possible for the transition to superhumanity.

And we lose that option by making the AI open source. Make such a program universally available, and while Dr. Good is busy testing and prodding, Dr. Amoral has already downloaded the program, flipped the switch, and away we go.

V.

Once again: The decision to make AI findings open source is a tradeoff between risks and benefits. The risk is that assuming hard takeoff and control problems – two assumptions that a lot of people think make sense – it leads to buggy superhuman AIs that doom everybody. The benefit is that in a world where intelligence progresses very slowly and AIs are easily controlled, nobody will be able to use their sole possession of the only existing AI to garner too much power.

But the benefits just aren’t clear enough to justify that level of risk. I’m still not really sure exactly how the OpenAI founders visualize the future they’re trying to prevent. Are AIs fast and dangerous? Are they slow and easily-controlled? Does just one company have them? Several companies? All rich people? Are they a moderate advantage? A huge advantage? None of those possibilities seem worrisome enough to justify OpenAI’s tradeoff against safety.

Suppose that AIs progress slowly and are easy to control, remaining dominated by one company but gradually becoming necessary for almost every computer user. Microsoft Windows is dominated by one company and became necessary for almost every computer user. For a while people were genuinely terrified that Microsoft would exploit its advantage to become a monopolistic giant that took over the Internet and something something something. Instead, they were caught flat-footed and outcompeted by Apple and Google, plus if you really want you can use something open-source like Linux instead. And anyhow, whenever a new version of Windows comes out, hackers have it up on the Pirate Bay in a matter of days.

Or are we worried that AIs will somehow help the rich get richer and the poor get poorer? This is a weird concern to have about a piece of software which can be replicated pretty much for free. Windows and Google Search are both fantastically complex products of millions of man-hours of research, and both are provided free of charge. In fact, people have gone through the trouble of creating fantastically complex competitors to both and providingthose free of charge, to the point where multiple groups are competing to offer people fantastically complex software for free. While it’s possible that rich people will be able to afford premium AIs, it is hard for me to weigh “rich people get premium versions of things” on the same scale as “human race likely destroyed”. Like, imagine the sort of dystopian world where rich people had more power than the rest of us! It’s too horrifying even to talk about!

Or are we worried that AI will progress really quickly and allow someone to have completely ridiculous amounts of power? Remember, there is still a government and they tend to look askance on other people becoming powerful enough to compete with them. If some company is monopolizing AI to become too big and powerful, the government will break it up, the same way they kept threatening to break up Microsoft when it was becoming too big and powerful. If someone tries to use AI to exploit others, the government can pass a complicated regulation against that. You can say a lot of things about the United States government, but you can never say that they don’t realize they can pass complicated regulations forbidding people from doing things.

Or are we worried that AI will be so powerful that someone armed with AI is stronger than the government? Think about this scenario for a moment. If the government notices someone getting, say, a quarter as powerful as it is, it’ll probably take action. So an AI user isn’t likely to overpower the government unless their AI can become powerful enough to defeat the US military too quickly for the government to notice or respond to. But if AIs can do that, we’re back in the intelligence explosion/fast takeoff world where OpenAI’s assumptions break down. If AIs can go from zero to more-powerful-than-the-US-military in a very short amount of time while still remaining well-behaved, then we actually do have to worry about Dr. Evil and we shouldn’t be giving him all our research.

Or are we worried that some big corporation will make an AI more powerful than the US government in secret? I guess this is sort of scary, but you can forgive me for not quite quaking in my boots. So Google takes over the world? Fine. Do you think Larry Page would be a better or worse ruler than one of these people? What if he had a superintelligent AI helping him, and also everything was post-scarcity? Yeah, I guess all in all I’d prefer constitutional limited government, but this is another supposed horror scenario which doesn’t even weigh on the same scale as “human race likely destroyed”.

If OpenAI wants to trade off the safety of the human race from rogue AIs in order to get better safety against people trying to exploit control over AIs, they need to make a much stronger case than anything I’ve seen so far for why the latter is such a terrible risk.

There was a time when the United States was the only country with nukes. While it did nuke two cities during that period, it otherwise mostly failed to press its advantage, bumbled its way into letting the Russians steal the schematics, and now everyone from Israel to North Korea has nuclear weapons and things are pretty okay. If we’d been so afraid of letting the US government have its brief tactical advantage that we’d given the plans for extremely unstable super-nukes to every library in the country, we probably wouldn’t even be around to regret our skewed priorities.

Elon Musk famously said that “AIs are more dangerous than nukes”. He’s right – so AI probably shouldn’t be open source any more than nukes should.

VI.

And yet Elon Musk is involved in this project. So are Sam Altman and Peter Thiel. So are a bunch of other people whom I know have read Bostrom, are deeply concerned about AI risk, and are pretty clued-in.

My biggest hope is that as usual they are smarter than I am and know something I don’t. My second biggest hope is that they are making a simple and uncharacteristic error, because these people don’t let errors go uncorrected for long and if it’s just an error they can change their minds.

But I worry it’s worse than either of those two things. I got a chance to talk to some people involved in the field, and the impression I got was one of a competition that was heating up. Various teams led by various Dr. Amorals are rushing forward more quickly and determinedly than anyone expected at this stage, so much so that it’s unclear how any Dr. Good could expect both to match their pace and to remain as careful as the situation demands. There was always a lurking fear that this would happen. I guess I hoped that everyone involved wassmart enough to be good cooperators. I guess I was wrong. Instead we’ve reverted to type and ended up in the classic situation of such intense competition for speed that we need to throw every other value under the bus just to avoid being overtaken.

In this context, the OpenAI project seems more like an act of desperation. Like Dr. Good needing some kind of high-risk, high-reward strategy to push himself ahead and allow at least some amount of safety research to take place. Maybe getting the cooperation of the academic and open-source community will do that. I won’t question the decisions of people smarter and better informed than I am if that’s how their strategy talks worked out. I guess I just have to hope that the OpenAI leaders know what they’re doing, don’t skimp on safety research. and have a process for deciding which results not to share too quickly. But I’m terrified that it’s come to this. It suggests that we really and truly do not have what it takes, that we’re just going to blunder our way into extinction because cooperation problems are too hard for us.

I am reminded of what Malcolm Muggeridge wrote as he watched World War II begin:

All this likewise indubitably belonged to history, and would have to be historically assessed; like the Murder of the Innocents, or the Black Death, or the Battle of Paschendaele. But there was something else; a monumental death-wish, an immense destructive force loosed in the world which was going to sweep over everything and everyone, laying them flat, burning, killing, obliterating, until nothing was left…Nor have I from that time ever had the faintest expectation that, in earthly terms, anything could be salvaged; that any earthly battle could be won or earthly solution found. It has all just been sleep-walking to the end of the night.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI

Statement from Max Tegmark on the Department of War’s ultimatum

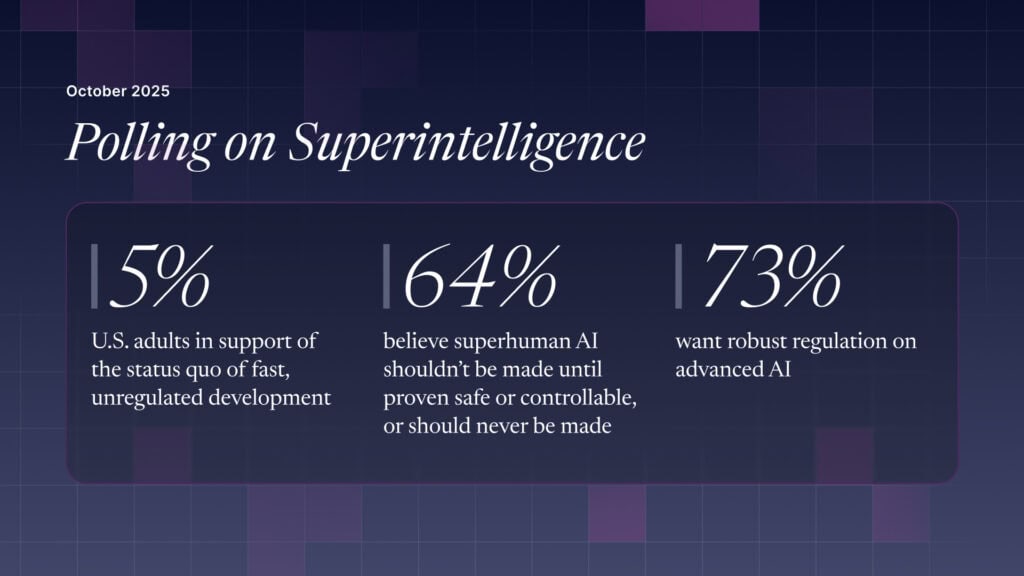

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI