Op-ed: When NATO Countries Were U.S. Nuclear Targets

Contents

Sixty years ago, the U.S. had over 60 nuclear weapons aimed at Poland, ready to launch. At least one of those targeted Warsaw, where, on July 8-9, allied leaders will meet for the biennial NATO summit meeting.

In fact, recently declassified documents, reveal that the U.S. once had their nuclear sites set on over 270 targets scattered across various NATO countries. Most people assume that the U.S. no longer poses a nuclear threat to its own NATO allies, but that assumption may be wrong.

In 2012, Alex Wellerstein created an interactive program called NukeMap to help people visualize how deadly a nuclear weapon would be if detonated in any country of the world. He recently went a step further and ran models to see how far nuclear fallout might drift from its original target.

It turns out, if the U.S. – either unilaterally or with NATO – were to launch a nuclear attack against Russia, countries such as Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, and even Poland would be at severe risk of nuclear fallout. Similarly, attacks against China or North Korea would harm people in South Korea, Myanmar and Thailand.

Even a single nuclear weapon, detonated too close to a border, on a day that the wind is blowing in the wrong direction, would be devastating for innocent people living in nearby allied countries.

While older targeting data is declassified, today’s nuclear targets have shifted. And the public is kept in the dark about how many countries may be at risk of becoming collateral damage in the event of a nuclear attack anywhere in their region of the globe.

Most people believe that no leader would intentionally fire a nuke at another country. And perhaps no sane leader would intentionally do so – although that’s not something to count on as political tensions increase – but there’s a very good chance that one of the nuclear powers will accidentally launch a nuke in response to inaccurate data.

The accidental launch of a nuclear weapon is something that has almost happened many times in the past, and it only takes one nuclear weapon to kill hundreds of thousands of people. Yet almost 30 years after the Cold War ended, 15,000 nuclear weapons remain, with more than 90% of them split between the U.S. and Russia.

Meanwhile, relations are deteriorating between Russia, China, and the US/ NATO. This doesn’t just increase the risk of intentional nuclear war; it increases the likelihood that a country will misinterpret bad satellite or radar data and launch a retaliatory strike to a false alarm.

Many nuclear and military experts, including Former Secretary of Defense William Perry, warn that the threat of a nuclear attack is greater now than it was during the Cold War.

Major international developments have occurred in the two years since the last NATO meeting. In a recent op-ed in Newsweek, NATO president Jens Stoltenberg overviewed many of the problems that they must address:

“There is no denying that the world has become more dangerous in recent years. Moscow’s actions in Ukraine have shaken the European security order. Turmoil in the Middle East and North Africa has unleashed a host of challenges, not least the largest refugee and migrant crisis since the Second World War. We face security challenges of a magnitude and complexity much greater than only a few years ago. Add to that the uncertainty surrounding “Brexit”—the consequences of which are unclear—and it is easy to be concerned about the future.”

These are serious problems indeed, but 15,000 nuclear weapons in the hands of just a couple leaders only increases global destabilization. If NATO is serious about increasing security, then we must significantly decrease the number of nuclear weapons – and the number of nuclear targets ― around the world.

Deterrence is an important defensive posture, and this is not a call for NATO to encourage countries to eliminate all nuclear weapons. Instead, it is a reminder that we must learn from the past. Those who are enemies today could be friends in a safer, more stable future, but that hope is lost if a nuclear war ever occurs.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Nuclear, Recent News

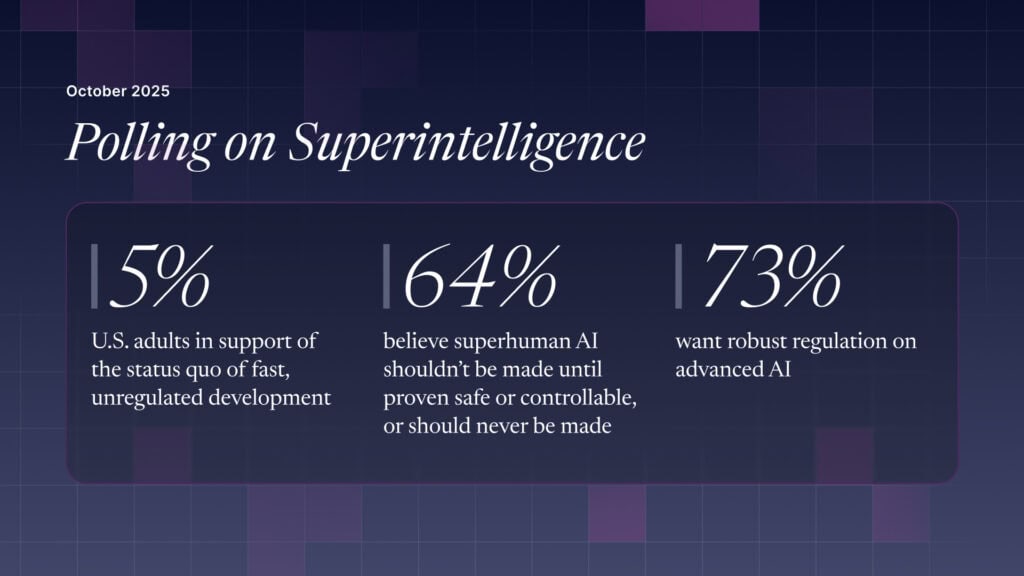

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI

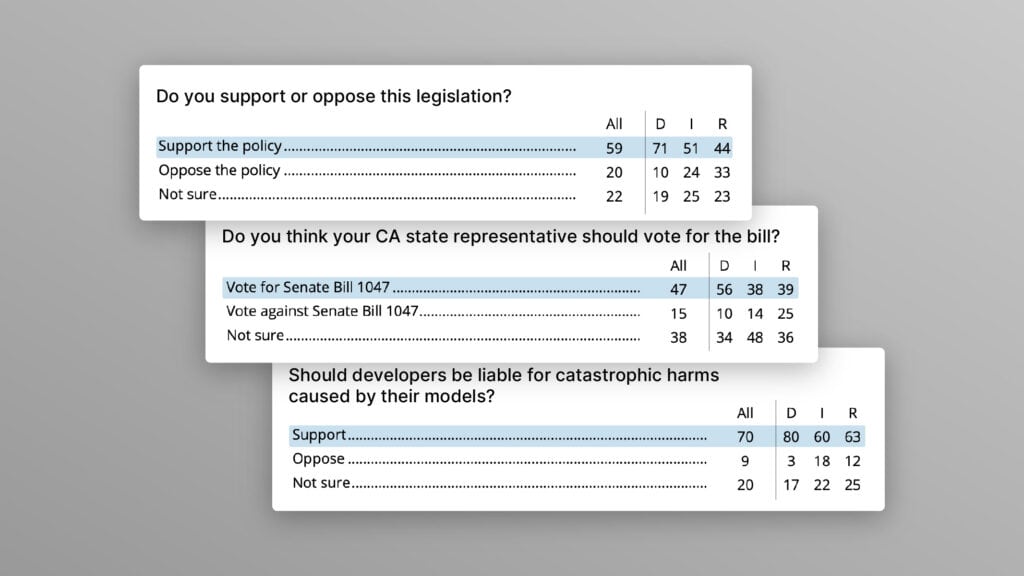

Poll Shows Broad Popularity of CA SB1047 to Regulate AI