X-risk or X-hope? AI Learns From Books & an Autonomous Accident

Contents

X-risk = Existential Risk. The risk that we could accidentally (hopefully accidentally) wipe out all of humanity.

X-hope = Existential Hope. The hope that we will all flourish and live happily ever after.

The importance of STEM training and research in schools has been increasingly apparent in recent years, as the tech industry keeps growing. Yet news coming out of Google and Stanford this week gives reason to believe that hope for the future may be found in books.

In an effort to develop better language recognition software, researchers at Google’s Natural Language Understanding research group trained their deep neural network to predict the next sentence an author would write, given some input. The team used classic literature found on Project Gutenberg. Initially, they provided the program with sentences but no corresponding author ID, and the program was able to predict what the following sentence would be with a 12.8% error rate. When the author ID was given to the system, the error rate dropped to 11.1%.

Then the team upped the ante. Using the writing samples and author ID, the researchers had the program apply the Meyers Brigg personality test to determine personality characteristics about the authors. The program identified Shakespeare as a private person and Mark Twain as outgoing.

Ultimately, this type of machine learning can enable AI to better understand both language and human nature. Though for now, as the team explains on their blog, the program “could help provide more personalized response options for the recently introduced Smart Reply feature in Inbox by Gmail.”

Meanwhile, over at Stanford, another group of researchers is using modern books to help their AI program, Augur, understand everyday human activities.

Today, as the team explains in their paper, AI can’t anticipate daily needs without human input (e.g. when to brew a pot of coffee or when to silence a phone because we’re sleeping). They argue this is because there are simply too many little daily tasks and needs for any person to program manually. Instead, they “demonstrate it is possible to mine a broad knowledge base of human behavior by analyzing more than one billion words of modern fiction.”

In other news, perhaps the development of machines that learn human behavior from fiction could be applied to systems such as Google’s driverless car, which, for the first time, accepted partial responsibility for an accident this week. Google’s cars have logged over 1 million miles of driving and been in about 17 accidents, however, in every other case, it was the fault of the human driving the other car, or it occurred when one of Google’s employees was driving the Google car.

This particular accident occurred because the Google car didn’t properly anticipate the actions of a bus behind it. The car swerved slightly to avoid an obstruction on the road, and the bus side-swiped the car. According to CNN, “The company said the Google test driver who was behind the wheel thought the bus was going to yield, and the bus driver likely thought the Google car was going to yield to the bus.”

The accident raises an interesting question to consider: How tolerant will humans be of rare mistakes made by autonomous systems? As we’ve mentioned in the past, “If self-driving cars cut the 32000 annual US traffic fatalities in half, the car makers won’t get 16000 thank-you notes, but 16000 lawsuits.”

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, Recent News

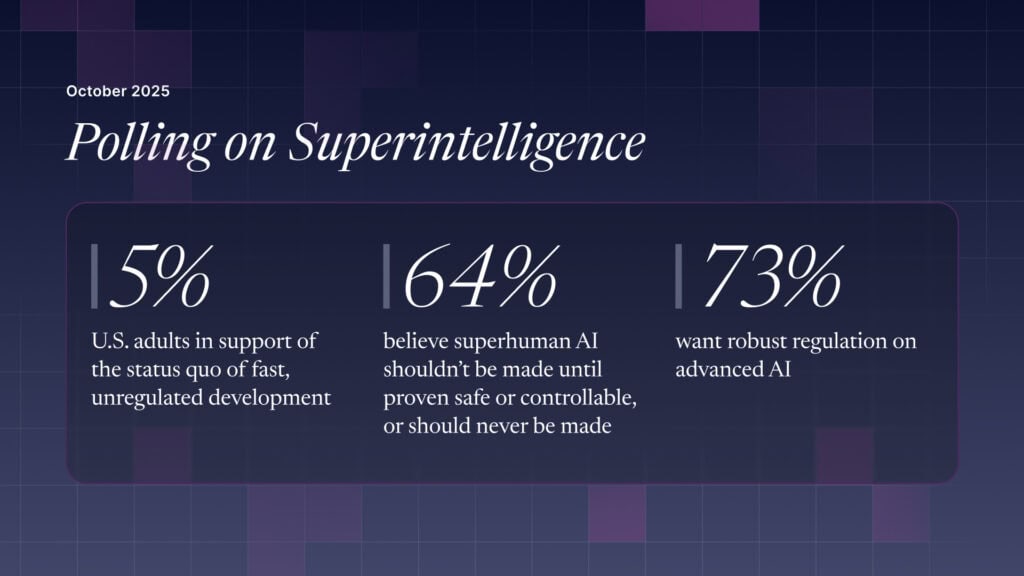

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI