Not Cool Ep 6: Alan Robock on geoengineering

What is geoengineering, and could it really help us solve the climate crisis? The sixth episode of Not Cool features Dr. Alan Robock, meteorologist and climate scientist, on types of geoengineering solutions, the benefits and risks of geoengineering, and the likelihood that we may need to implement such technology. He also discusses a range of other solutions, including economic and policy reforms, shifts within the energy sector, and the type of leadership that might make these transformations possible.

Topics discussed include:

- Types of geoengineering, including carbon dioxide removal and solar radiation management

- Current geoengineering capabilities

- The Year Without a Summer

- The termination problem

- Feasibility of geoengineering solutions

- Social cost of carbon

- Fossil fuel industry

- Renewable energy solutions and economic accessibility

- Biggest risks of stratospheric geoengineering

Publications discussed include:

- Florida’s Utilities Keep Homeowners From Making the Most of Solar Power, The New York Times (2019)

- Climate Intervention Reports, National Academy of Sciences (2015)

- Albedo enhancement by stratospheric sulfur injection: More research needed, Alan Robock (2016), includes benefits and risks of geoengineering.

We have to move to stop emitting carbon dioxide, and the question is: are the impacts of global warming going to be so serious that we might want to use this temporary thing, — I liken it to a tourniquet — for a while before we get there, before we can solve the problem, before we can stop the bleeding?

~ Alan Robock

Transcript

Ariel Conn: Hello and welcome to episode 6 of Not Cool: a climate podcast. I’m your host, Ariel Conn.

So far, we’ve talked a lot about the causes of the climate crisis, the impacts it might have, and the ways we can cope with those impacts. Today, we’re talking about ways of possibly mitigating the crisis itself. I’m joined by Dr. Alan Robock, meteorologist and geoengineering expert, who will be answering some big questions about what geoengineering is, how it would work, and how feasible it really would be.

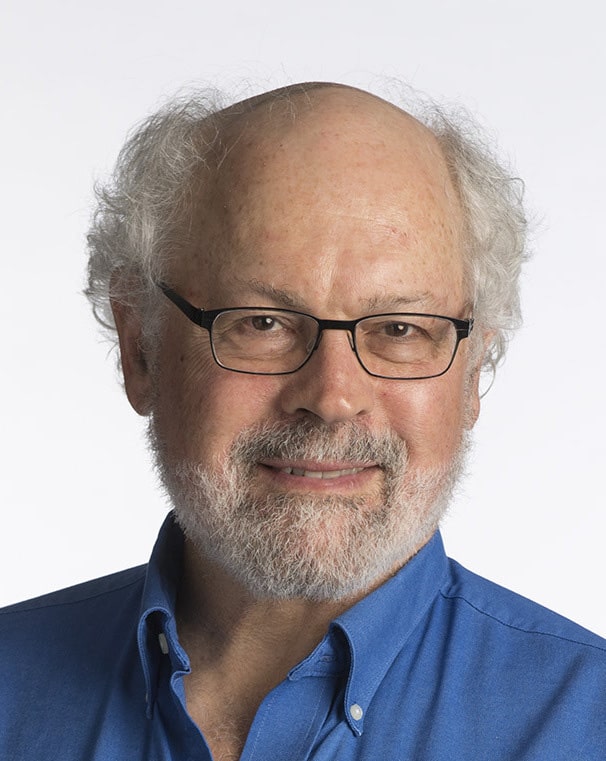

Alan is a Distinguished Professor of climate science in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers University. His areas of expertise include geoengineering, climatic effects of nuclear war, effects of volcanic eruptions on climate, and soil moisture. He was a Lead Author of the 2013 Working Group 1 Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and a contributor to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, both of which won Nobel Peace Prizes.

Alan, thank you so much for joining us.

Alan Robock: Oh, my pleasure.

Ariel Conn: We've brought you on — your background is in nuclear winter, among other things; you're also a climate scientist — but you look at how climate can be affected by introducing particulates, I guess, into the atmosphere, and you can correct how I'm phrasing that. So I wanted to bring you on first and most generally just to explain what geoengineering is.

Alan Robock: Alright, so first my background. I'm a meteorologist. I've studied climate change for my entire career, for more than 40 years, and recently, I've been studying the effects of particles that would go into the upper atmosphere: either naturally, through volcanic eruptions, or because humans might put them there, either on purpose for cooling the climate, to emulate a volcanic eruption, or as a byproduct of nuclear war — in which case, a lot of smoke from the fires would go up there. So about geoengineering. First of all, let me make clear: global warming is real. It's caused by us. Overall, it's going to be bad, and we're sure; But there is hope, and the solution to global warming is to leave the rest of the fossil fuels — the coal and oil and gas — in the ground. Don't burn it and dump it into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide; Don't use the atmosphere as a sewer for our greenhouse gases. There's a few other gases like methane and nitrous oxide which are also important, but carbon dioxide is the most important one.

And we know how to do that. It's called mitigation. We can switch to sun and wind as our source of energy. We'd know how to do that too if we start paying a sewage fee for CO2. Right now, we don't pay to dump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, but you do pay when you have your trash taken out. So if there was a gradual increasing fee on that, then that would help solve the problem, because there would be a huge incentive to produce ways that we can go somewhere, or cook our food, or turn on lights without producing carbon dioxide. And people would have the incentive to do it, because it would be cheaper. The problem is that it's not happening very fast. In fact, the emissions are going up. So people have said, "Well, we don't see that happening fast enough. Maybe we want to do something else to prevent the largest global warming," and that's called geoengineering.

Geoengineering is really not a good term because it really means pushing earth around, so now we use the term, "climate engineering," or "climate intervention." And it comes in two flavors: One is to try to take the carbon dioxide back out of the atmosphere, called carbon dioxide removal, and you can do that by growing trees, or planting trees where they aren't now, and the new trees are made of carbon that was in the atmosphere. You can even cut them down, and bury them, and plant more trees. There are also ways of sucking the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere chemically, and that takes a lot of energy. We know how to do it. Right now it's very expensive to do that, and then we'd have to figure out where to put all the carbon dioxide, but there are probably underground storage areas that could be used.

That's probably a good idea if it could be done cheaply enough and on a large enough scale, but it's too expensive now. So people are doing research on trying to figure that out, and if we do that, that will take a long time, and it's the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that causes the warming, and so we would have to take it out at a rate faster than we're putting it in, and by the time we get to that, that would be a ways into the future.

So the other way is called solar radiation management, SRM, and this is trying to reflect sunlight so less energy comes in, and that would balance the extra energy that's trapped by the greenhouse gases. The idea that's gotten the most traction, that people have studied the most, is to emulate a big volcanic eruption. Big volcanic eruptions pump sulfur dioxide gas into the stratosphere, which is a layer above the troposphere where we live. In the stratosphere, there's no rain to wash it out. It reacts with water to form a thin cloud of sulfuric acid droplets, and they can last for a couple years. So if we could put a cloud up there like a volcano does, then that would reflect sunlight and cool the earth. Because it has a fairly short lifetime, you'd have to continuously replenish it: A volcanic eruption puts a cloud up there, and then in a few years, it's gone. So this is the idea that people are studying to try and see whether it would be a good idea or not.

Ariel Conn: And so just for historic reference, this would be similar to what happened with The Year Without a Summer?

Alan Robock: Yes. The volcano was called Tambora, and it erupted in 1815 in Indonesia, and the next year has been called The Year Without a Summer because it was much colder in Europe and eastern North America, and there was frost every month in New England, for example. We wouldn't want to make it that cold, and it wasn't cold everywhere in the world; But the places that we know about, it was cold. And so that's the basic mechanism, that a cloud of particles would reflect sunlight and cool it off.

Ariel Conn: One of the things that I think is interesting is you said Tambora was in Indonesia, and yet, the impact on summer happened the following year in the northern part of the hemisphere. Is that correct?

Alan Robock: Well, it happened globally.

Ariel Conn: Oh, okay.

Alan Robock: If you put particles into the stratosphere in the tropics, the atmospheric circulation will blow them around the world, and they will last long enough for that to happen. The lifetime of a particle in the lower atmosphere is about a week — but in the stratosphere, it's about a year for a third of it to be gone. And so putting it up that high would be 50 times more effective because it would last 50 times longer, and that's why the idea is putting it in the stratosphere. In the tropics, the stratospheric circulation is upward, and then toward the Pole, and so it would spread around the world. And we have good observations of that after the last big volcanic eruption, Mount Pinatubo, in 1991 in the Philippines. The cloud was seen around the world, and we were able to measure it with satellites.

We also have ice cores in Greenland and Antarctica where, of course — particles that go up, sulfur that goes up into the stratosphere has to come out, and it comes out as acid snow over these ice sheets, and gets buried, and so we can take a core out of the ice, and find layers of enhanced sulfur, which had been in the atmosphere from big volcanic eruptions. In fact, that's the best way we know to measure the history of big volcanic eruptions.

Ariel Conn: So that's volcanic eruptions. Are current plans for putting particles up into the stratosphere made of different components, or are we still looking to face things like acid snow?

Alan Robock: Well, first of all, there are no plans. There are just schemes that people have proposed, but nobody's actually planning to do it. In fact, if you wanted to do it tomorrow, you couldn't, because the technology doesn't exist. We've looked at, "How would you do it if you wanted to do it?" And it seems like the cheapest way in theory would be with airplanes flying up there and spraying SO2 gas, or sulfuric acid droplets. But there are no current airplanes that could do that, so they would have to be invented. Current ones can't fly that high and carry that much stuff. So in theory, they could; there have been some designs — but it would take a decade at least of development to produce them.

And yes, SO2, sulfur, is the chemical that's been studied the most because we know a lot about it. That's what volcanic eruptions do. We know of the potential benefits and risks, and sulfur's cheap. People have suggested other particles, however — calcium carbonate, or even diamond particles. We looked at soot, by the way, with my graduate student, Ben Kravitz, and you could probably de-tune a diesel engine and create a cloud of black soot, but that would be a terrible idea because it would heat the atmosphere a lot and destroy all the ozone, and you also don't want all that falling out, so that's not a good idea.

If you're putting sulfur up there in equilibrium, the same amount you put up every year comes out, and so there would be enhanced acid rain and acid snow, and depending on how much you put up there, that could be a concern. It just depends how much cooling you want to get. People are trying to think about other types of particles, but nobody has come up with something that would work as well, if it would work at all.

Ariel Conn: So you mentioned the equilibrium issue, which also means that since it's going to come out, we have to keep putting it back up. And my understanding is that seems to be a problem as well, that if we don't continuously put these particles up into the stratosphere, then at some point, we're going to start to have global warming again.

Alan Robock: That's right. The only reasonable plan would be to try and shave off the worst impacts of global warming. So, right now we're on track to be one and a half degrees celsius above pre-industrial, and the IPCC has determined that 1.5 or two degrees above pre-industrial is a limit that we should not exceed. But given the pledges of countries right now as part of the Paris agreement, we'll probably get up to three degrees, and who knows whether those pledges will be carried out. I think probably countries will be able to reduce their emissions much more easily than they plan right now, but let's say we're on a track for three or four degrees. We might want to put enough of a cloud in the stratosphere to bring that warming down to, say, two degrees. And then as we figure out how to reduce our emissions, as we figure out how to take the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere cheaply on a large scale, then gradually we would reduce the cloud in the stratosphere as the warming from carbon dioxide would go down.

So the idea would be to, for a limited time, have a cloud up there, and then ramp it down as the warming from the greenhouse gases goes down. In an optimistic scenario, however, that might take 50 or 100 years. So if you're in the middle of this period, and you stop taking the sulfur up there, then after a year or two, it would all be gone, and you would have rapid warming at a rate much faster than we're experiencing now. This is called the termination problem. People who think geoengineering might be a good idea say, "Oh, that would be stupid. Nobody would do that; Even if you're going to turn it off, you would turn it off gradually.” But it's not hard to think of a scenario where it would happen catastrophically. There could be a war, or there could be a technology failure of the means of getting it up there, or what happens if you're doing it, and there's a big flood in China, or a big drought in India, and they say, "You geoengineers. You're causing that. We demand that you stop," and you say to them, "Well, you can't really prove that we did it. Every once in a while there are droughts and floods." "We don't care. You better stop or we're going to shoot your airplanes down."

You can imagine that people that are unhappy with climate would blame it on the geoengineers, and would demand reparations, and they wouldn't get them, and they would say, "Okay, stop," and so then you would have this rapid warming, and that termination issue is one of the potential risks.

Ariel Conn: Can we actually control where these clouds go and how they impact different regions, or is that we just sort of put these particulates up and hope for the best?

Alan Robock: So you have to take one step back and say, "What temperature do you want the planet to be?" Another way of saying it is, "Whose hand would be on the thermostat?" What if Russia and Canada wanted it a bit warmer because they can exploit the Arctic, and not spend as much on heating — where at the same time, islands in the Pacific that are drowning because of sea level rise want it even lower than it is now? Who's going to decide what temperature we want the planet? So that's another problem.

But let's assume we could decide that. Then, you can't control the regional climate. You can control the global average. You could put the particles in at different latitudes or even different times of the year to try and have a little bit of control, and there have been some climate model experiments by putting it in at different latitudes to not only keep the temperature from going up, but keeping the temperature difference between the tropics and the polar regions from changing. And so that could be done, but regionally, you still are going to get more cooling over land than over the ocean, and you're going to get a reduction of precipitation if the temperature is constant, and if you want precipitation not to change, then temperature's got to go up, so if you can't control temperature and precipitation at the same time, you certainly can't tailor the climate of a small region without affecting the whole rest of the globe.

On top of that is the issue of natural variability, or chaos in the atmospheric system. Because the way the system is, it behaves unpredictably within a certain range. A few days ago, there was a month's worth of rain dumped on Washington DC and caused flooding because it overwhelmed the sewer system. Today, there was 11 inches of rain in New Orleans as a big rain band went through there that was connected to an incipient tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico. You'll never be able to control those things or predict them very far in advance, and so superimposed on this natural variability, the global average temperature is slowly going up, and extremes are going up — the probability of extremes is going up; But you can't predict on a particular day what the temperature or precipitation will be.

It's hard to detect climate changes because the climate system is so noisy. However, humans experience weather. We don't experience climate. And so when you get something that happens to you like the big floods in the Midwest that we had this year, or what happened in New Orleans, you can say, "Well, that — clearly the climate's changing. That has never happened before," and so it's a statistical argument. But when you control the climate, and keep it from warming as much, you're still going to get these episodes. The probability of getting the extremes will go down. So it's hard to sort of detect: Even if something extreme happens when you're doing geoengineering, you can't say it's caused by geoengineering. You could say, in fact, maybe it would be less likely to happen during geoengineering, but you still got it.

Ariel Conn: So earlier you mentioned that technologies for carbon capture and technologies for stratospheric engineering don't really exist yet anyway, and you mentioned that there's possibly some hope that we could develop the technology for stratospheric geoengineering as we try to figure out our other issues and get carbon capture figured out. Do you think then that the technology for the stratospheric geoengineering is going to be easier than carbon capture, or do you think that we could end up figuring out how to address carbon capture first?

Alan Robock: Well, the technology for carbon capture already exists. It's just expensive: It costs a couple hundred dollars a ton to take it out of the atmosphere. We know — we have several direct air capture schemes, and people are working also on biological schemes, growing algae in tanks and things like that. It's just — it's already been done. It's being done on a very small scale and in fact some of the carbon dioxide is being used to pump for what's called enhanced oil recovery, to pump down into oil wells to push more oil out — which is probably not the best usage of it, but it's being used for that, and so we know how to do it. It's just expensive, and so the question is, "Can we develop a way to do it much more cheaply?" And so the people are doing research on that. Unknowns by definition are unknown. I don't know how easy it is, and I'm not an engineer, whether to expect that to get cheap very fast.

As far as the stratosphere, with existing designs of airplanes, it probably wouldn't be expensive at all. Estimates are on the order of $50 to $100 billion a year, cutting global warming in half for doubling CO2. And I think the technology to fly an airplane is pretty well known — you'd have to design wings and engines that would actually get you a little bit higher than you can now. Again, I'm not an engineer, but as I understand it, there really aren't probably any showstoppers, but we should try to see if we can invent them to see how easy or hard it is. One of the issues people bring up is that it might be too cheap. $100 billion a year is so much cheaper than completely changing the energy structure of our society, and people might be tempted to do that without working very hard on mitigation and reducing emissions.

Ariel Conn: And what's your response to those people?

Alan Robock: One response is ocean acidification is destroying the ocean and the ocean food chain, and even if carbon dioxide didn't cause global warming, we should still stop putting it in the atmosphere, so we have to do it anyway, no matter what. Another response is, well, so, people say to me, "What are you working on?" "Geoengineering." "What is that?" "Okay, here's the story: We're going to fly an airplane over your daughter's school, and spray sulfuric acid in the air, and that's going to solve the global warming problem." "What? You're thinking about something that crazy? Gee, global warming must really be a serious problem. I should pay more attention to it, and work harder to not put CO2 in the atmosphere." It may actually produce more mitigation if people learn about it. So I don't think anybody thinks that continued emission of greenhouse gases and blocking out the sun permanently is a good idea because, as we discussed, the termination problem would always be there. I think that's kind of a bogus argument. I think we have to move to stop emitting carbon dioxide, and the question is: are the impacts of global warming going to be so serious that we might want to use this temporary thing, — I liken it to a tourniquet — for a while before we get there, before we can solve the problem, before we can stop the bleeding?

Ariel Conn: Do you think that there is a chance this will be something we have to resort to, or do you think we'll be able to avoid it?

Alan Robock: Have to, or we're going to need to do it, is a value judgment, is a political decision; It's never a scientific decision. And so the question is: can the world organize itself well enough to agree to do this or not? Because if it's not a global decision, then there's always going to be some losers. Maybe most people would be better off, but some people would be worse off. One of the impacts might be a reduction of the summer monsoon precipitation. That's a pretty robust result because when you cool the earth by blocking out the sun, the land cools more than the ocean, and it's the temperature difference between the land and the ocean that drives the summer monsoon, which produces rain in India and China, and the Saha region of Africa. And so if you reduce the rain, there's going to be less rain there for agriculture. We've actually observed this response after big volcanic eruptions; It's a very robust response. So people might argue, "Well, okay. We still need to cool the earth because we're getting way too many strong storms, and sea level's rising too much, and you people are just going to have to deal with less rain." So I think it's going to be really hard to ever agree on that. I think we're going to need not to do it, actually, because you could produce global war if people can't agree on it.

Ariel Conn: I'm going back to the carbon capture again. You talked about those as being expensive and pretty energy intensive as well.

Alan Robock: Yeah, that's why they're expensive.

Ariel Conn: Okay. Are they at least systems that are using renewable energy, or are we looking at carbon capture programs or systems that are still using fossil fuels?

Alan Robock: Well, they basically use electricity, so you can get that from several sources. There are certainly enough windmills and solar panels in the world to power the small experimental systems that are going now. Specifically, I don't know for each one whether they're using natural gas, or whether they're using hydropower, or what. It would have to be cheap enough, use little enough energy, that it would be effective. I said a couple hundred dollars a ton, so if there was a carbon fee, if people had to pay a couple hundred dollars a ton to emit CO2 into the atmosphere, every product that you used that emitted CO2 either directly or indirectly from a factory in China or whatever had this tax added onto it, and you could keep track of that, then today, it would be effective to capture CO2. It's called the social cost of carbon. Right now, people's discussions are a much smaller fee — $20, $50 a ton.

You'd have to decide what that fee would be, and if it started off small and was gradually going up, at some point it would cross the cost of taking it out of the atmosphere, and the people would make money by taking it out of the atmosphere because they would get a credit for taking it out. And so it's a decision that governments have to make, how to organize this. And we know that that would work, those cap and trade systems that have helped solve the acid rain problem in the US.

But there’s also these fee and dividend schemes, and one of the ideas that Jim Hanson has pushed, and other people, is if you have a carbon tax, the government doesn't keep it: you give it back to the people. So every person, say, in the United States would get a dividend. All the money that was paid would go back to the people. Every adult would get the same amount of money. So if you live your life and emit less CO2 than average, you'd make money during the year, and if you emit more than average, you would be paying more. So you wouldn't have to trust the government to use the money wisely on something else. That might be much more politically acceptable than another tax the government would take, which is very unpopular.

But if the price was gradually going up, and people could count on that happening, there would be a huge incentive to produce all kinds of electric transportation, or industrial processes that would not produce CO2. Already, the price of solar panels and wind power is going down, and it's already cheaper than coal in the United States, and that's why coal plants are closing: not because of environmental regulations. Natural gas is pretty cheap right now because it's pretty plentiful, but that's temporary. But that emits CO2, also, when you burn it — it emits half as much per amount of energy as burning coal or oil, but still, it's not a safe fuel; It's not good for the climate. So when you get to the point where it's cheaper to use solar panels than it is to use natural gas, that's going to happen faster than it's happening already.

It's clear that the fossil fuel industry, which is making lots of money on selling you the stuff that there's no fee to emit, is standing in the way of mitigation. And they control the Republican party in the United States and the White House right now, and they're trying to stand in the way of these policies, which both by requiring cars to be efficient, but also by putting in a carbon tax would solve the problem. And so it's really a political problem, not a technical problem, solving the global warming issue.

Ariel Conn: I don't know if we want the comment I'm about to make to stay in the podcast. I saw an article recently saying that all these companies still want the US to be part of the Paris Climate Agreement. Even companies like Exxon want the US to be part of the Paris Climate Agreement, and the reason is because they want to be able to have a say in the negotiations, and as soon as I saw that, I was like, "Oh, God. Maybe it's better if we're not part of it."

Alan Robock: Well, there's a bipartisan plan in Congress to implement a carbon fee, and even some of the oil companies are onboard with it with one stipulation: they'll agree to it if the country agrees not to hold them responsible for all the climate change that's been produced in the past by the use of their products when they knew it was happening and lied to us about it. So you remember the tobacco companies lied about impacts of their products and they were caught, and they had to pay huge fees to every state as part of the reparations. So the oil companies are really worried about that, because we know that they knew about global warming, and spent lots of money to try and confuse the public. And so they think this might help them in the short term, if it's agreed that they will not be held responsible then they'll help solve the problem in the future. I don't know whether that's going to happen or not, but anyway, that's one way I heard that some of the fossil fuel companies would get onboard.

Ariel Conn: Wow.

Alan Robock: Right now I think the fossil fuel companies are just trying to make as much money as they can before they are forced to go away. I think only Chevron is actually investing heavily in green technology. The others are just doing their business. In fact, in Alaska where they extract oil, they even spent extra money to keep the permafrost from melting so that their equipment doesn't sink into the ground.

Ariel Conn: That’s actually one thing that I've never understood, is why the oil companies don't just embrace this new technology that will clearly make them money in the future.

Alan Robock: Because they’re making more money now by not doing that. That would require investments, and they feel like they're beholden to their stockholders to make as much money as they can, and that's the only ethical stance they have — the only value they have is to make as much money as they can, and not look at all kinds of other ethical considerations. So that's what's wrong with the system.

Let me just say I really don't want to be working on geoengineering, because I know that we know how to solve the problem of global warming. There's enough sun and wind on it to power the whole earth. The technology doesn't have to be invented. It already exists. We just need some better storage and better grids, and we can solve the problem. I've got solar panels on the roof of my house. I live at 40 degrees north in New Jersey, and I get more energy every year than I use from that. So we know how to solve the problem. It's just that it's not being done very fast. I wish I could work on something else because this is pretty frustrating.

Ariel Conn: That's something that I'm curious... I'm assuming that you paid for the solar panels. Is that correct or do you get assistance from the government for that?

Alan Robock: The state of New Jersey paid for more than half of them. They gave me a grant, and then the state of New Jersey has renewable energy certificates. They have a requirement that the electric companies generate a certain amount of energy renewably, and they don't have the capacity, so they buy credits from people that do it for them, and so I get about — it used to be $.60 a kilowatt hour; now it's about $.20 a kilowatt hour. I get $.22 for these certificates; Plus I get the electricity. And so it's already paid for itself, but that's a government regulation that helps solve the problem. Every state is different, though, and in some states the utilities are stronger, and so they don't allow you to run your meter backwards — it's called net metering — and so if you put more on your house than you can use, then it just disappears. And others have fees for hooking up electricity: They have this bogus claim that it hurts their grid or something. And so in some places, the regulations really favor it and really encourage you to do it. This 50% grant program is over now but the federal government will pay for 33% of it right now when you put on solar panels. In some places, you don't get these renewable energy certificates. In New Jersey, you do. So that's sort of an example of how government can be part of the solution.

Ariel Conn: Obviously, this is a problem that needs to be solved at individual level, local level, state level, federal level, international level, etc. But your example right now implies that at least for things like this, people really need to be active in their local governments to make change happen. And I don't know how you stand up to the utilities.

Alan Robock: The way I would say it is it's more important to change your leaders than it is to change your light bulbs. So it really has to come from the government. You can do your own thing, but there really needs a national and statewide regulation. Now, some of the states — like California, New Jersey, and other states — are really leaders in this, and other states aren't so much. The federal government was trying to do something under President Obama, and now it's working against solving this problem under the current administration. And so if you want to be blunt about it, if you get rid of the Republican control of our government, then we'll be able to solve the problem much quicker. They can accept unlimited contributions. The fossil fuel companies have lots and lots of money and they pay them not to change it, so that's the situation we're in right now. So you need young people to work in politics to get rid of the people that make the rules, and you can do whatever you want as far as driving an electric car and riding your bicycle and stuff, but on a large scale, the government has to set the rules both by regulations and by taxing.

For example, the Obama administration had rules that vehicles have to get up to 50-some miles per gallon and Trump is trying to get rid of that regulation. California has an exemption. They can still make cars be required to be very efficient, and because they are such a big market, it's much easier for the automobile companies to only design one type of car rather than two separate models. And so even the automobile companies are pushing back on this reduction of the regulations because if they have a rule, they know what the rule is, and everybody has to follow the same rule, then they'll do it, and they'll be fair to all the different companies. So they're even pushing back. They've made plans to have electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles, and now somebody might not have to do that, so it's confusing if the rules keep changing.

I do what I can personally, but I still think you have to change your leaders. In most of the world they get it, but in the US, and Saudi Arabia, and a few other places are sort of standing in the way right now.

Ariel Conn: Are these the countries that are making the most off of fossil fuels?

Alan Robock: Yeah.

Ariel Conn: Yeah.

Alan Robock: And the US is an exporter of oil now. Saudi Arabia, all their wealth is underground in their oil. They don't want it to be banned.

Ariel Conn: Your example with California was another reason to especially be concerned about state politics because it can have that big impact. The reason I had asked about how you paid for the solar panels is there's lots of people who have lower incomes, and I don't know what the easier solutions for them is if there are big upfront costs.

Alan Robock: Well, there are huge subsidies to the fossil fuel companies by the federal government, so if they would stop those and subsidize green technology, then that would help solve the problem, if people got help doing it.

Ariel Conn: I think I'm ready to switch back to a question I was going to ask earlier, but we'll come back to this because I do want to ask you more. Solutions is sort of one of the big things that I think the public needs to see more of. We get a lot of, "This is awful and the future's going to be terrible," but we don't seem to get — at least I don't see as much in the way of solutions.

Alan Robock: The way I would put it is, we produced this problem and we can solve it. It's produced by humans; It can be solved by humans. It's not out of our control — we caused it. If you think that the fossil fuel companies are going to run the country for the rest of your life and nothing can change, then you might want to give up, but if you support the Green New Deal, which includes a lot of the things we've been talking about, then we can solve the problem. It's up to people to vote. That's the most important thing people can do. And climate change has never been an important issue in elections in the past, and I think it was a little bit important in the 2018 election, and it actually will be important in this election. So people have to be concerned about it enough to make it one of the important issues.

Ariel Conn: Yeah, one of the reasons that I want to do this now is to remind people that we have big important elections coming up in 2020, so vote. And again, not just at a federal level: it's important to vote at all the levels, because local politics can play a role.

Alan Robock: Yeah, everybody's going to be voting for their member of Congress in the House. All of them are up for election, and a third of the Senate is, and the President is, so there's important things to vote on for everybody — as well as at local level. In New Jersey, we don't have elections in sync with the federal ones; There won't be any governors election or legislature election in 2020, — but most states there will be, and so you should ask people what their position is on all these issues. For example, I saw an article recently comparing solar power in Florida versus California. Both have a lot of sun but there's almost none in Florida because the electric companies are so strong in putting blocks in the way of people putting their own solar panels on their roof. They claim that it's dangerous; They have to spend a lot for insurance. They've enacted all these rules that make it harder for people to do it. Where I live it was easy.

Ariel Conn: Okay, I am going to pull us back to geoengineering for a minute. There's two more things that I definitely want to bring up. One is the idea of rogue geoengineers. I don't remember the details of the story, but I know someone somewhat recently, maybe in the last year or so, I think off of the coast of Canada or northern US, was arrested for trying to do sort of a pseudo-test of a geoengineering system; And there's all these horror stories at least I hear of the potential for people — you know, you get a billionaire to decide that they want to solve the problem, and they go up without anyone's permission, or a single country decides to unilaterally start spraying clouds into the stratosphere. What do you think the risks are associated with that? Is this idea of a rogue geoengineer actually something we should be worried about, or do you think that's easy to prevent, or it's harder than we think for someone to become a rogue geoengineer?

Alan Robock: As I said, the technology doesn't exist today to do it, so nobody could do it if they wanted to do it. They would have to develop it and test it. I got a telephone call about seven years ago, and these two guys said, "Hi. We're consultants working for the CIA. Can we ask you a question?" And I said, "Yes." They said, "If some other country was trying to control our climate, would we know about it?" And I thought about it for a while, and I said, "Yes, we would.” If they created a cloud in the stratosphere that was thick enough to cause climate change, it would have to persist and be pretty large, and we could observe it with satellites from the ground, and we could see the airplanes going up there, so we could — or another technique we haven't discussed yet is the idea of brightening clouds out over the ocean by spraying particles into them from the ocean surplus, which is much more problematic; it's not clear that that would work, but that's another idea — but we would see those activities taking place. And they said, "Thank you. Goodbye." And after they hung up, I thought, "They're probably asking me another question too: 'If we wanted to control somebody else's climate, would they know about it?'"

And in fact, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report four years ago on geoengineering — they called it climate intervention, and they had two books, one on carbon dioxide removal, and the other on solar radiation management, reflecting sunlight. And the study was mostly funded by the CIA. I guess they're just doing their job. So people say, "Well, Richard Branson claims to be an industrialist. He has a lot of airplanes. Maybe he'll just do it on his own," or some country where sea level's going up too fast, or they're getting too many droughts decides they're going to do it. You couldn't do it in secret, so then if the rest of the world didn't agree, they would sanction them either by talking to them or militarily, so it's a potential risk of doing it. It's a conflict between countries if the world can't agree.

Ariel Conn: And so that's a nice segue to the last question I want to ask. We've gone over this throughout the whole discussion but I wanted to specifically look at what do you think the biggest risks of stratospheric geoengineering are, or what would worry you the most?

Alan Robock: I have a list of 28 risks or concerns about it. I also have a list of the potential benefits. If you could do it, the number one benefit is it would reduce global warming and reduce the negative impacts of global warming: fewer floods, fewer droughts, lower sea level rise — so the question is, can we live with all these risks and do it? That's what we're doing research on, to try and quantify them.

But my risks are in different categories. One is the physical and biological climate system. It would produce drought in certain regions. It would destroy ozone. It would not do anything about continued ocean acidification. We'd have additional acid rain and snow, and rapid warming if it stopped — the termination problem. And then there's human impacts. There'd be less solar energy generation, effects on airplanes flying in the sulfuric acid bath in the stratosphere. It'd affect remote sensing from satellites — you'd be looking down through this cloud — or affect astronomy from the ground. And then there's aesthetic things. I don't know how to quantify them. You wouldn't have blue skies anymore, couldn't see the Milky Way anymore.

But the things that worry me most are the governance and unknowns, so potential human error. If you were in a car recently, you probably wore your seatbelt, so you understand this principle very well: anything made by humans, anything operated by humans, can fail. And God forbid you have an accident, the seatbelt would help you, but it would be a small-scale thing. But if we have one system controlling the climate of the only planet known to sustain intelligent life, then what if something goes wrong? What if somebody makes a mistake? And you can think of other more complicated, technological systems like airplanes crash, or nuclear power reactors, or dams fail, or whatever. That's something I worry about.

And then there's unexpected consequences. Donald Rumsfeld was right about one thing: There are unknown unknowns. We don't even know what might happen. There would also be unexpected benefits — we don't know about that either. But just the unknown: I think you'd have to worry about that, and then what about commercial control? What if you get like the Exxon Geoengineering Corporation or whatever, and they have jobs in every country, and they say, "Oh, we can't stop now. You'll lose jobs, and we'll keep going," and they would have influence to keep it going because of their financial wealth. Right now the United States is building military planes that nobody wants because of the military industrial complex: They've convinced Congress to keep paying for it because there's jobs in their district. So I worry about it not being able to actually be controlled well by politicians.

And we had a conference at Asilomar about 10 years ago on this — maybe a little bit more than 10 years ago — and it was about the ethics of geoengineering; and it was held at Asilomar because that's where genetic engineering was discussed a couple of decades earlier. And at the end of the week, a professor from Princeton was going around asking people, "What's the worst thing you think could happen if we do geoengineering?" It was Rob Socolow and he said, "The winner of my survey is global nuclear war," because if different countries are upset about other countries trying to control the climate, and you say, "Well, I'm just trying to improve agriculture in my country," and you'd say, "Yeah, but you're causing droughts in my country," and so you could have conflict. And so I think it's going to be very difficult for the world to agree on implementing a system that has so many unknowns and so many potential losers as well as winners, even if they promise to compensate the losers.

When you build a dam, and people get moved out of the valley, or you do urban renewal, the people that get moved don't really end up better off. And this would be a system that would have to last for decades and decades. What institution and government do you know of that could be able to have enough resources to always compensate the losers, and how would you know even who the losers are? It's a statistical thing. So there might be increased frequency of droughts in your area, so every time there's a drought, you're going to say, "I demand money from the compensation fund," and it's hard to attribute that to geoengineering. So I think the governance of this, and potential conflict because of this, are the things I worry about most.

Ariel Conn: Do you think this is something that we'll resort to?

Alan Robock: So, I know how to forecast the weather a few days in advance, but forecast human behavior decade in advance, it's not my area of expertise. But based on what I know, the answer is no, I don't think it'll ever happen.

Ariel Conn: Okay. I think it would be really nice to have a fair list of both benefits and risks. Are your lists publicly available?

Alan Robock: Oh, yeah.

Ariel Conn: Then we'll include links to that.

Alan Robock: There's a paper I wrote in 2016, and it's on my website, and — in red on my website — table one here has my list.

Ariel Conn: Okay. Excellent. Yeah, we'll definitely link to that in the podcast. Alright, so I want to end with what is hopefully an optimistic question. What do you see as a realistic, yet ideal solution to the problem of climate change? As you've said, we can technically solve this.

Alan Robock: So, we worry about tipping points in the climate system — methane bubbling up as permafrost melts, or catastrophic collapse of ice sheets — but there are also tipping points in human behavior. Imagine 10 years ago legalized pot, black president, gay marriage. These things change very quickly. They didn't cost as much as changing the whole energy system, but so my utmost optimistic scenario is a charismatic leader who will educate people about what we all need to do together to solve this problem for our children and our grandchildren. And the problem is it's a long-term problem: if you start riding a bicycle and get rid of your Hummer, the climate's going to be the same tomorrow, so it's sort of an investment in the future for our children and grandchildren, not for us. But we can have charismatic leaders who’ve led people to do that. And the technology exists, like the program that put the man on the moon in less than a decade. We can do this. We just need the will to do it, and so that's my optimistic scenario of what's going to happen.

Ariel Conn: Excellent. Are you optimistic that that will happen?

Alan Robock: Yes.

Ariel Conn: Yay.

Alan Robock: My work on geoengineering is to quantify the risks and the benefits, and so if sometime in the future, society is tempted to use this, they'll be able to make an informed policy decision. And so far, the risks look pretty daunting to me, but we still have to quantify them and do a better job of understanding what these potential impacts are, and then people will be able to make a decision about the future. And if it looks — rather than being a slippery slope to deployment, it might work in the other direction: It might be clear soon that it's so risky there's no plan B, and we have to work even harder on mitigation.

Ariel Conn: Alright. Is there anything else that you think we should have covered that we didn't get into?

Alan Robock: It's a hard problem because we have to make some sacrifices now to have a better future — and the sacrifices wouldn't be that hard though, I mean, the resources exist. We could solve the nuclear war problem and the climate problem at the same time by taking the vast resources that go into the military right now, and devote them to building a better electrical grid, and better battery research, and we certainly have the resources there to give everybody healthcare, and to solve the global warming problem. And so it's a question of wresting control from the people that are spending our tax money and using it in a different direction, and there are some leaders in Congress who are talking about this and some candidates for president who are talking about it — and so it's possible to solve the problem, and it's just we need the will to do it.

Ariel Conn: Alright. So I think the message there again is go vote.

Alan Robock: Yes, go vote. Educate yourself about the policies of the candidates, and prioritize climate change, and vote.

Ariel Conn: Alright. I think that's an excellent note to end on, so thank you very much for joining the series.

Alan Robock: You're welcome. My pleasure.

Ariel Conn: On the next episode of Not Cool, I’ll be speaking with Lindsay Getschel. Lindsay researches environmental security, and she’ll be talking to us about the national security implications of the climate crisis.

Lindsay Getschel: We're extremely globalized now. Our economies all are interrelated. And what happens in one place may seem distant, but it actually has direct impacts on what's going on in the US or in other wealthier countries around the world.

Ariel Conn: I hope you enjoyed this sixth episode of Not Cool. My interview with Lindsay will go live on Thursday, September 19th. In the meantime, please join the climate discussion on Twitter using #NotCool and #ChangeForClimate and let us know what you think of the show so far.

Related episodes

Can AI Do Our Alignment Homework? (with Ryan Kidd)

How AI Can Help Humanity Reason Better (with Oly Sourbut)