Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work: An Interview With Moshe Vardi

Contents

“The future of work is now,” says Moshe Vardi. “The impact of technology on labor has become clearer and clearer by the day.”

Machines have already automated millions of routine, working-class jobs in manufacturing. And now, AI is learning to automate non-routine jobs in transportation and logistics, legal writing, financial services, administrative support, and healthcare.

Vardi, a computer science professor at Rice University, recognizes this trend and argues that AI poses a unique threat to human labor.

Initiating a Policy Response

From the Luddite movement to the rise of the Internet, people have worried that advancing technology would destroy jobs. Yet despite painful adjustment periods during these changes, new jobs replaced old ones, and most workers found employment. But humans have never competed with machines that can outperform them in almost anything. AI threatens to do this, and many economists worry that society won’t be able to adapt.

“What people are now realizing is that this formula that technology destroys jobs and creates jobs, even if it’s basically true, it’s too simplistic,” Vardi explains.

The relationship between technology and labor is more complex: Will technology create enough jobs to replace those it destroys? Will it create them fast enough? And for workers whose skills are no longer needed – how will they keep up?

To address these questions and consider policy responses, Vardi will hold a summit in Washington, D.C. on December 12, 2017. The summit will address six current issues within technology and labor: education and training, community impact, job polarization, contingent labor, shared prosperity, and economic concentration.

Education and training

A 2013 computerization study found that 47% of American workers held jobs at high risk of automation in the next decade or two. If this happens, technology must create roughly 100 million jobs.

As the labor market changes, schools must teach students skills for future jobs, while at-risk workers need accessible training for new opportunities. Truck drivers won’t transition easily to website design and coding jobs without proper training, for example. Vardi expects that adapting to and training for new jobs will become more challenging as AI automates a greater variety of tasks.

Community impact

Manufacturing jobs are concentrated in specific regions where employers keep local economies afloat. Over the last thirty years, the loss of 8 million manufacturing jobs has crippled Rust Belt regions in the U.S. – both economically and culturally.

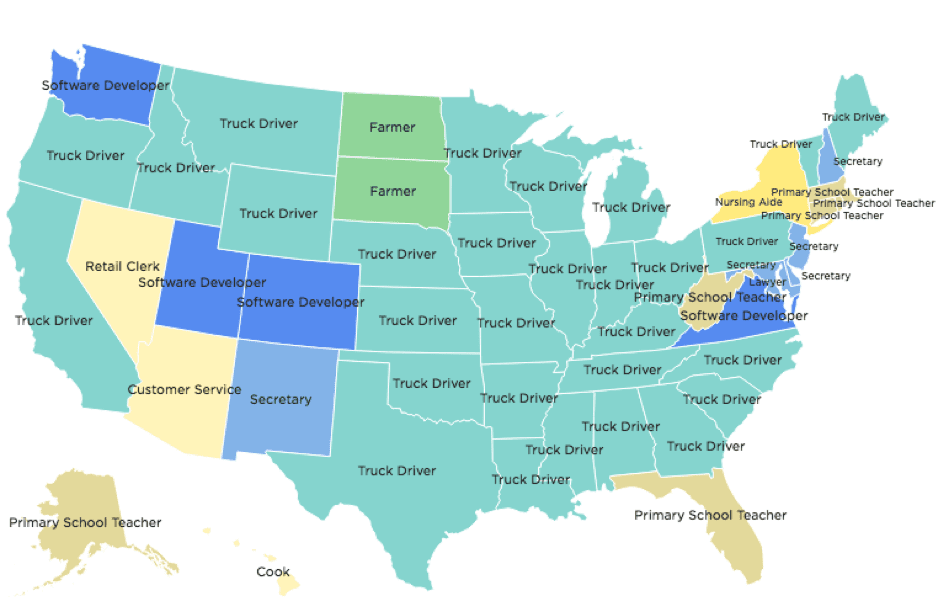

Today, the fifteen million jobs that involve operating a vehicle are concentrated in certain regions as well. Drivers occupy up to 9% of jobs in the Bronx and Queens districts of New York City, up to 7% of jobs in select Southern California and Southern Texas districts, and over 4% in Wyoming and Idaho. Automation could quickly assume the majority of these jobs, devastating the communities that rely on them.

Job polarization

“One in five working class men between ages 25 to 54 without college education are not working,” Vardi explains. “Typically, when we see these numbers, we hear about some country in some horrible economic crisis like Greece. This is really what’s happening in working class America.”

Employment is currently growing in high-income cognitive jobs and low-income service jobs, such as elderly assistance and fast-food service, which computers cannot automate yet. But technology is hollowing out the economy by automating middle-skill, working-class jobs first.

Many manufacturing jobs pay $25 per hour with benefits, but these jobs aren’t easy to come by. Since 2000, when millions of these jobs disappeared, displaced workers have either left the labor force or accepted service jobs that often pay $12 per hour, without benefits.

Truck driving, the most common job in over half of US states, may see a similar fate.

Contingent labor

Increasingly, communications technology allows firms to save money by hiring freelancers and independent contractors instead of permanent workers. This has created the Gig Economy – a labor market characterized by short-term contracts and flexible hours at the cost of unstable jobs with fewer benefits. By some estimates, in 2016, one in three workers were employed in the Gig Economy, but not all by choice. Policymakers must ensure that this new labor market supports its workers.

Shared prosperity

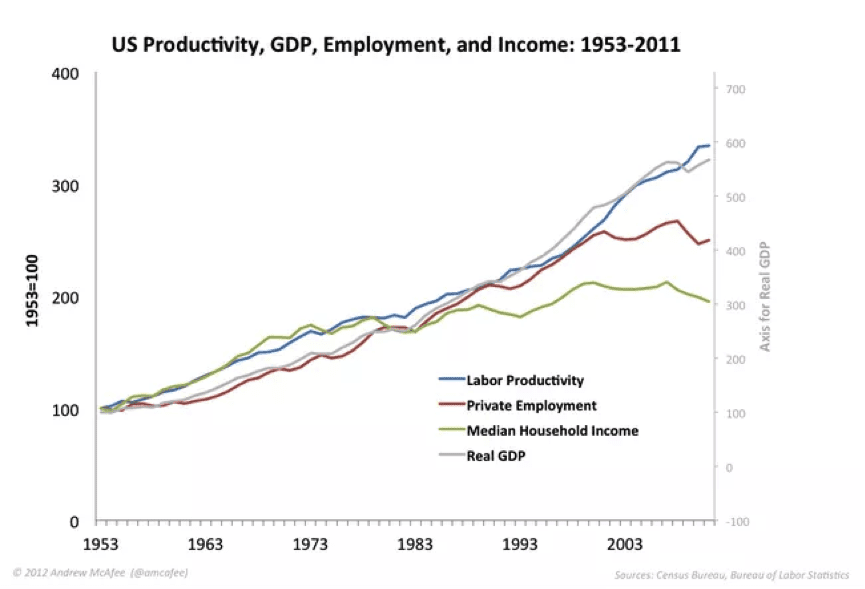

Automation has decoupled job creation from economic growth, allowing the economy to grow while employment and income shrink, thus increasing inequality. Vardi worries that AI will accelerate these trends. He argues that policies encouraging economic growth must also support economic mobility for the middle class.

Economic concentration

Technology creates a “winner-takes-all” environment, where second best can hardly survive. Bing search is quite similar to Google search, but Google is much more popular than Bing. And do Facebook or Amazon have any legitimate competitors?

Startups and smaller companies struggle to compete with these giants because of data. Having more users allows companies to collect more data, which machine-learning systems then analyze to help companies improve. Vardi thinks that this feedback loop will give big companies long-term market power.

Moreover, Vardi argues that these companies create relatively few jobs. In 1990, Detroit’s three largest companies were valued at $65 billion with 1.2 million workers. In 2016, Silicon Valley’s three largest companies were valued at $1.5 trillion but with only 190,000 workers.

Work and society

Vardi primarily studies current job automation, but he also worries that AI could eventually leave most humans unemployed. He explains, “The hope is that we’ll continue to create jobs for the vast majority of people. But if the situation arises that this is less and less the case, then we need to rethink: how do we make sure that everybody can make a living?”

Vardi also anticipates that high unemployment could lead to violence or even uprisings. He refers to Andrew McAfee’s closing statement at the 2017 Asilomar AI Conference, where McAfee said, “If the current trends continue, the people will rise up before the machines do.”

This article is part of a Future of Life series on the AI safety research grants, which were funded by generous donations from Elon Musk and the Open Philanthropy Project.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, AI Research, Grants Program, Recent News

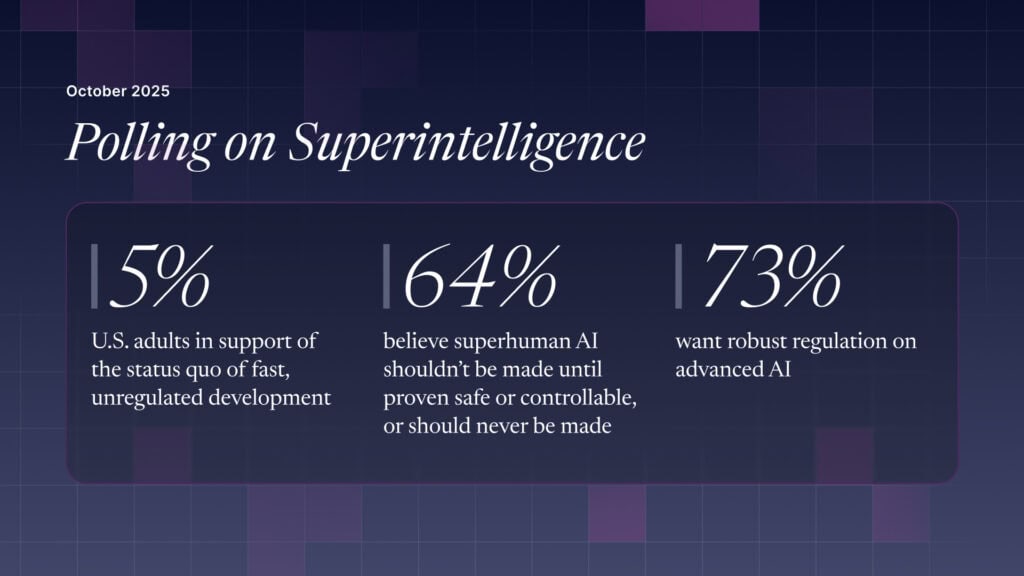

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI