Who is Responsible for Autonomous Weapons?

Contents

Click here to see this page in other languages: Chinese ![]()

Consider the following wartime scenario: Hoping to spare the lives of soldiers, a country deploys an autonomous weapon to wipe out an enemy force. This robot has demonstrated military capabilities that far exceed even the best soldiers, but when it hits the ground, it gets confused. It can’t distinguish the civilians from the enemy soldiers and begins taking innocent lives. The military generals desperately try to stop the robot, but by the time they succeed it has already killed dozens.

Who is responsible for this atrocity? Is it the commanders who deployed the robot, the designers and manufacturers of the robot, or the robot itself?

Liability: Autonomous Systems

As artificial intelligence improves, governments may turn to autonomous weapons — like military robots — in order to gain the upper hand in armed conflict. These weapons can navigate environments on their own and make their own decisions about who to kill and who to spare. While the example above may never occur, unintended harm is inevitable. Considering these scenarios helps formulate important questions that governments and researchers must jointly consider, namely:

How do we hold human beings accountable for the actions of autonomous systems? And how is justice served when the killer is essentially a computer?

As it turns out, there is no straightforward answer to this dilemma. When a human soldier commits an atrocity and kills innocent civilians, that soldier is held accountable. But when autonomous weapons do the killing, it’s difficult to blame them for their mistakes.

An autonomous weapon’s “decision” to murder innocent civilians is like a computer’s “decision” to freeze the screen and delete your unsaved project. Frustrating as a frozen computer may be, people rarely think the computer intended to complicate their lives.

Intention must be demonstrated to prosecute someone for a war crime, and while autonomous weapons may demonstrate outward signs of decision-making and intention, they still run on a code that’s just as impersonal as the code that glitches and freezes a computer screen. Like computers, these systems are not legal or moral agents, and it’s not clear how to hold them accountable — or if they can be held accountable — for their mistakes.

So who assumes the blame when autonomous weapons take innocent lives? Should they even be allowed to kill at all?

Liability: from Self-Driving Cars to Autonomous Weapons

Peter Asaro, a philosopher of science, technology, and media at The New School in New York City, has been working on addressing these fundamental questions of responsibility and liability with all autonomous systems, not just weapons. By exploring fundamental concepts of autonomy, agency, and liability, he intends to develop legal approaches for regulating the use of autonomous systems and the harm they cause.

At a recent conference on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Asaro discussed the liability issues surrounding the application of AI to weapons systems. He explained, “AI poses threats to international law itself — to the norms and standards that we rely on to hold people accountable for hold states accountable for military interventions — as able to blame systems for malfunctioning instead of taking responsibility for their decisions.”

The legal system will need to reconsider who is held liable to ensure that justice is served when an accident happens. Asaro argues that the moral and legal issues surrounding autonomous weapons are much different than the issues surrounding other autonomous machines, such as self-driving cars.

Though researchers still expect the occasional fatal accident to occur with self-driving cars, these autonomous vehicles are designed with safety in mind. One of the goals of self-driving cars is to save lives. “The fundamental difference is that with any kind of weapon, you’re intending to do harm, so that carries a special legal and moral burden,” Asaro explains. “There is a moral responsibility to ensure that [the weapon is] only used in legitimate and appropriate circumstances.”

Furthermore, liability with autonomous weapons is much more ambiguous than it is with self-driving cars and other domestic robots.

With self-driving cars, for example, bigger companies like Volvo intend to embrace strict liability – where the manufacturers assume full responsibility for accidental harm. Although it is not clear how all manufacturers will be held accountable for autonomous systems, strict liability and threats of class-action lawsuits incentivize manufacturers to make their product as safe as possible.

Warfare, on the other hand, is a much messier situation.

“You don’t really have liability in war,” says Asaro. “The US military could sue a supplier for a bad product, but as a victim who was wrongly targeted by a system, you have no real legal recourse.”

Autonomous weapons only complicate this. “These systems become more unpredictable as they become more sophisticated, so psychologically commanders feel less responsible for what those systems do. They don’t internalize responsibility in the same way,” Asaro explained at the Ethics of AI conference.

To ensure that commanders internalize responsibility, Asaro suggests that “the system has to allow humans to actually exercise their moral agency.”

That is, commanders must demonstrate that they can fully control the system before they use it in warfare. Once they demonstrate control, it can become clearer who can be held accountable for the system’s actions.

Preparing for the Unknown

Behind these concerns about liability, lies the overarching concern that autonomous machines might act in ways that humans never intended. Asaro asks: “When these systems become more autonomous, can the owners really know what they’re going to do?”

Even the programmers and manufacturers may not know what their machines will do. The purpose of developing autonomous machines is so they can make decisions themselves – without human input. And as the programming inside an autonomous system becomes more complex, people will increasingly struggle to predict the machine’s action.

Companies and governments must be prepared to handle the legal complexities of a domestic or military robot or system causing unintended harm. Ensuring justice for those who are harmed may not be possible without a clear framework for liability.

Asaro explains, “We need to develop policies to ensure that useful technologies continue to be developed, while ensuring that we manage the harms in a just way. A good start would be to prohibit automating decisions over the use of violent and lethal force, and to focus on managing the safety risks in beneficial autonomous systems.”

Peter Asaro also spoke about this work on an FLI podcast. You can learn more about his work at http://www.peterasaro.org.

This article is part of a Future of Life series on the AI safety research grants, which were funded by generous donations from Elon Musk and the Open Philanthropy Project.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global think tank with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about AI, AI Research, Grants Program

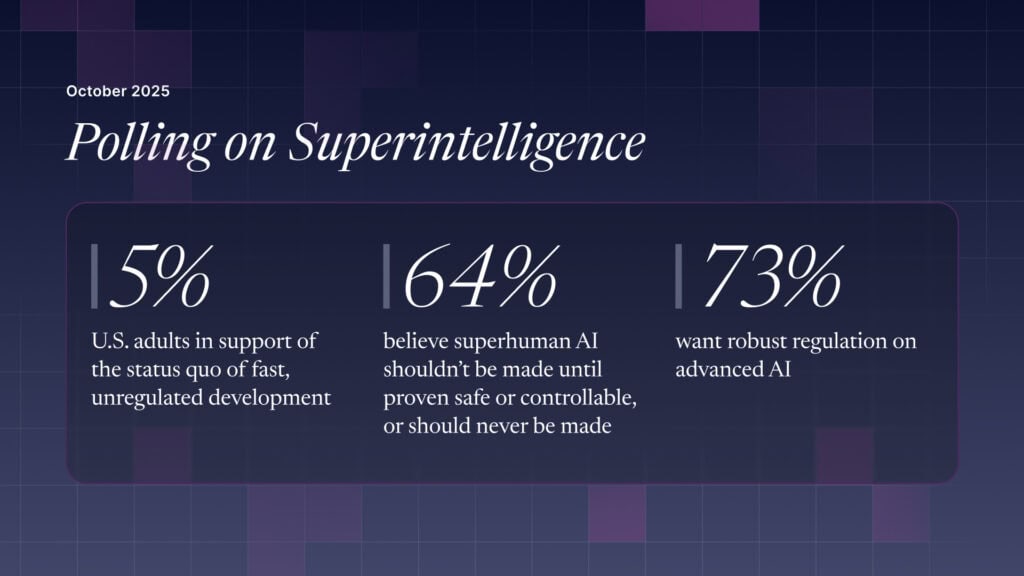

The U.S. Public Wants Regulation (or Prohibition) of Expert‑Level and Superhuman AI