Secretary William Perry Talks at Google: My Journey at the Nuclear Brink

Contents

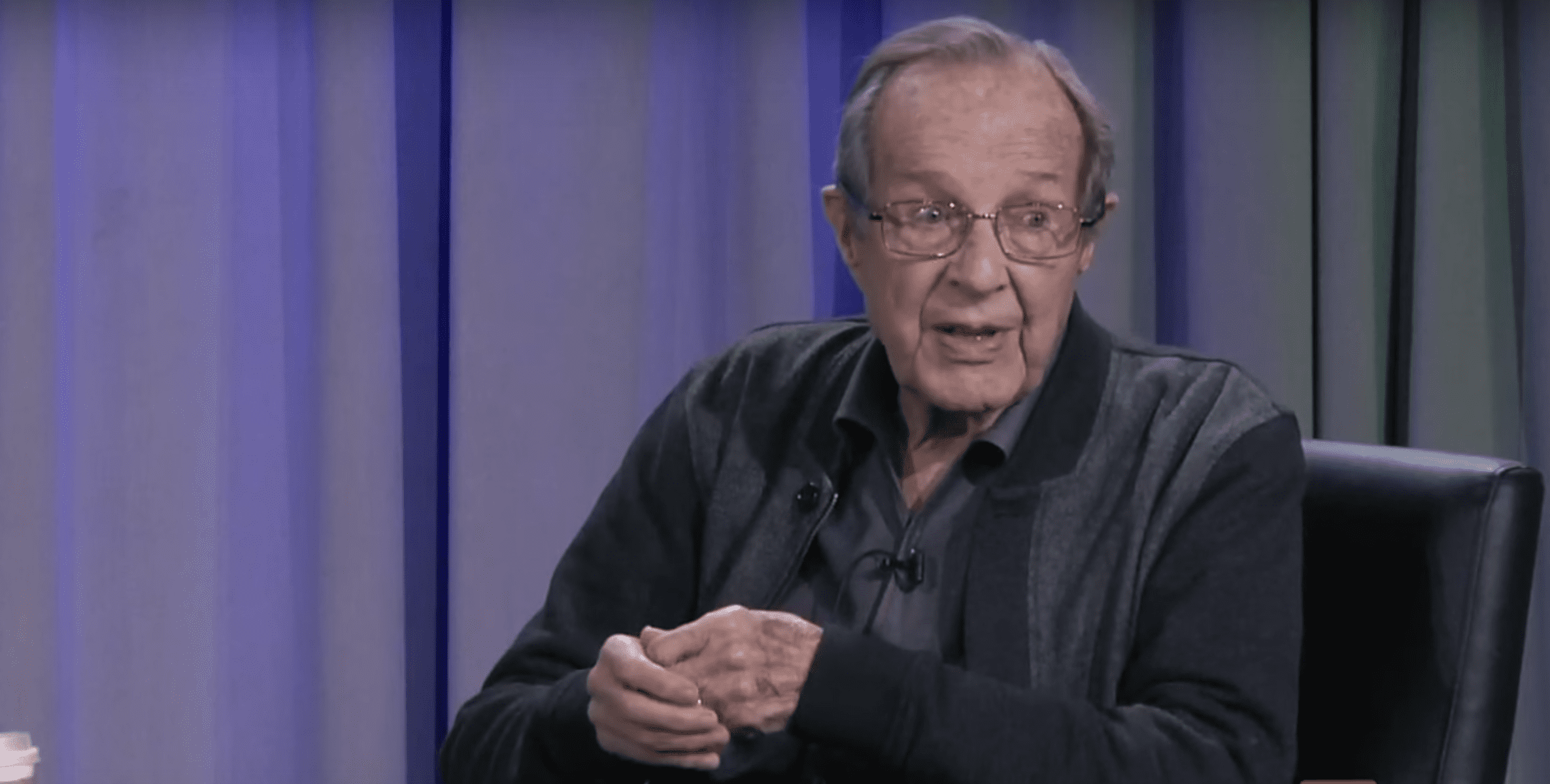

Former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry was 14 years old when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. As he humorously explained during his Talk at Google this week, in his 14-year-old brain, he was mostly upset because he was worried the war would be over before he could become an Army Air Corps pilot and fight in the war.

Sure enough, the war ended one month before his 18th birthday. He joined the Army Engineers anyway, and was sent to the Army occupation of Japan. That experience quickly altered his perception of war.

“What I saw in Tokyo and Okinawa changed my view altogether about the glamour and the glory of war,” he told the audience at Google.

Tokyo was in ruins — more devastated than Hiroshima — after two years and thousands of firebombs. He then went to Okinawa, which was the site of the last great battle of WWII. The battle had dragged on for nearly three months, during which, 100,000 Japanese had attempted to defend the city in that battle. By the end 90,000 of the Japanese fighters had perished. Perry described his shock upon arriving there to see the city completely demolished — not one building was left standing, and the people who had survived were living in the rubble.

“And then I reflected on Hiroshima,” he said. “This was what could be done with thousand pound bombs. In the case of Tokyo, thousands of them over a two-year period, and with thousands of bombers delivering them. The same result in Hiroshima, in an instant, with one airplane and one bomb. Just one bomb. Even at the tender age of 18, I understood: this changed everything.”

This experience helped shape his understanding of and approach to modern warfare.

Fast forward to the Cuban Missile Crisis. At the start of the crisis, he was working in California for a defense electronics company, but also doing pro-bono consulting work for the government. He was immediately called to Washington D.C. with other analysts to study the data coming in to try to understand the status of the Cuban missiles.

“Every day I went into that analysis center I believed would be my last day on earth. That’s how close we came to a nuclear catastrophe at that time,” he explained to the audience. He later added, “I still believe we avoided that nuclear catastrophe as much by good luck as good management.”

He then spoke of an episode, many years later, when he was overseeing research at the Pentagon. He got a 3 AM call from a general who said his computer was showing a couple hundred nuclear missiles launched from Russia and on their way to the U.S. The general had already determined that it was a false alarm, but he didn’t understand what was wrong with his computer. After two days studying the problem, they figured out that the sergeant responsible for putting in the operating tape had accidentally put in a training tape: the general’s computer was showing realistic simulations.

“It was human error. No matter how complex your systems are, they’re always subject to human error,” Perry said of the event.

He personally experienced two incidents – one of human error and one of system error – which could easily have escalated to the launch of our own nuclear missiles. His explanation for why the people involved were able to recognize these were false alarms was that “nothing bad was going on in the world at that time.” Ever since, he’s wondered what would have happened if these false alarms had occurred during a crisis while the U.S. was on high alert. Would the country have launched a retaliation that could have inadvertently started a nuclear war?

To this day, nuclear systems are still subject to these types of errors. If an ICBM launch officer gets the warning that an attack is imminent s/he will notify the President, who will then have approximately 10 minutes to decide whether or not to launch the missiles before they’re destroyed. That’s 10 minutes for the President to assess the context of all problems in the world combined with the technical information and then decide whether or not to launch nuclear weapons.

In fact, one of Perry’s biggest concerns is that the ICBMs are susceptible to these kinds of false of alarms. He acknowledges that the probability of an accidental nuclear war is very low.

“But,” he says, “why should we accept any probability?”

Adding to that concern is the Obama Administration’s decision to rebuild the nuclear arsenal, which will cost American taxpayers approximately $1 trillion over the next couple of decades. Yet there is very little discussion about this plan in the public arena. As Perry explains, “So far the public is not only not participating in that debate, they’re not even aware of what’s going on.”

Perry is also worried about nuclear terrorism. During the talk, he describes a hypothetical situation in which a terrorist could set off a strategically placed nuclear weapon in a city like Washington D.C. and use that to bring the United States and even the global economy to its knees. He explains that the one reason a scenario like this hasn’t played out yet is because fissile material is so hard to come by.

Throughout the discussion and the Q&A segment, North Korea, India, Pakistan, Iran, and China all came up. While commenting on North Korea, he said:

“The real danger of a missile is not the missile, it’s the fact that it could carry a nuclear warhead.”

That said, of all possible nuclear scenarios, he believes an intentional, regional nuclear war between India and Pakistan could be the most likely.

Perry served as Secretary of Defense from 1994 to 1997, and in more recent years, he’s become a strong advocate for reducing the risks of nuclear weapons. In addition to his many accomplishments and achievements, Perry was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1997.

We highly recommend the Talks at Google interview with Perry. We also recommend his new book, My Journey at the Nuclear Brink. You can learn more about his efforts to decrease the risks of nuclear destruction at the William J. Perry Project.

While Perry mentioned two nuclear close calls, there have been many other over the years. We’ve put together a timeline of close calls that we know about – there have likely been many others.

About the Future of Life Institute

The Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a global non-profit with a team of 20+ full-time staff operating across the US and Europe. FLI has been working to steer the development of transformative technologies towards benefitting life and away from extreme large-scale risks since its founding in 2014. Find out more about our mission or explore our work.

Related content

Other posts about Nuclear, Partner Orgs, Recent News

US Senate Hearing ‘Oversight of AI: Principles for Regulation’: Statement from the Future of Life Institute

FLI on “A Statement on AI Risk” and Next Steps

Statement on a controversial rejected grant proposal